Confirmation by the Andean testimonials

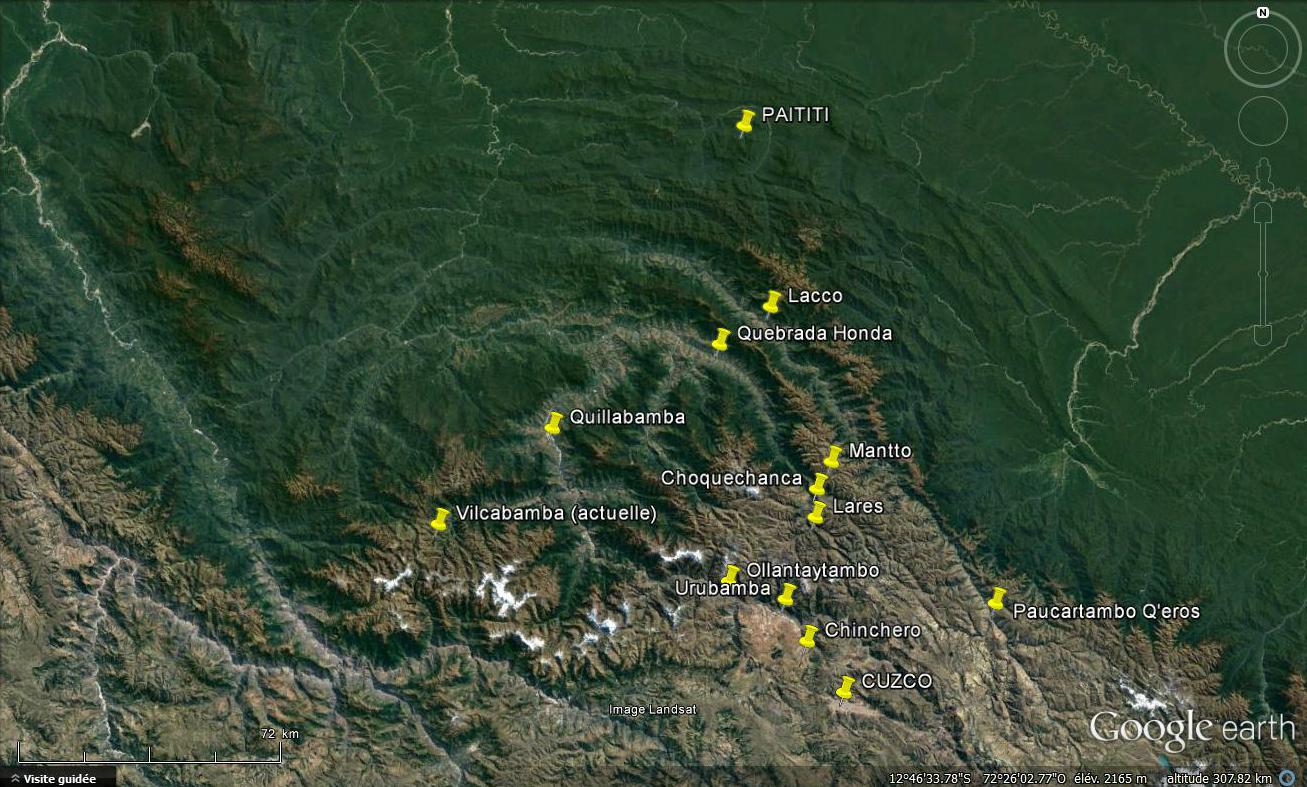

It’s from the village of Paucartambo at the birth of the Cordillera of the same name, in the Q’eros people area that the anthropologists Oscar Nunez del Prado and Efrain Morote Best of the National University of Cusco collected the first version of the Q’eros Legend of Inkarri, the Inca King who sought refuge in Paititi, here supplemented by the information gathered later by Gregory Deyermendjian:

When the Spaniards arrived at Cusco, the Incas were killed and persecuted for their money and gold. Some fled to Ollantaytambo. The Inkari (the term designating the Incas kings by identifying them all with this mythical hero), who had founded the village of Q’ero and Cusco, again went through Q’ero fleeing to Païtiti, taking away the gold kero (Ceremonial vase ). He would have left the testimony of his passage in the form of prints which can still be seen in places called Mujirumi and Iñaki Yupin, which could be verified. It then followed an ancient road, a northern extension of the Qapaq Q’ero Ñan, towards Pantiacolla (or Pantay Qoya or Pantilla Qoya), a vast plateau of plains, mountains, streams and swollen rivers, foggy forests, extends far to the north in the middle of the lower jungle. They say that Inkarri stayed there for the rest of his days in the tropical oasis of “Païtiti” which is still hidden somewhere on the mysterious plateau.

The Q’eros are a completely atypical people: they were “discovered” by anthropologists only in 1955, still living totally isolated according to customs, language and Inca lifestyle, and it is still in mayor part the case today. What is incredible is that they occupy a territory located realy not so far to the northeast of Cusco: it says a lot about the secular inaccessibility and lack of knowledge on the area beyond …

Other testimonies on the existence of Paititi, coming from populations living all along this cordillera of Paucartambo are also very interesting:

In the area of Chinchero and Urubamba (crossing points between Cusco and Ollantaytambo), but also to the north still in the vicinity of Quillabamba and Vilcabamba (the present one), the locals firmly believe that Paititi was the refuge of the Incas , and some of them even claim that their ancestors were formerly communicating with Paititi without knowing exactly where this city was located in the jungle. Fernando Jorge Soto Roland who recorded these testimonies always emphasized the visible fear and the great respect of his sources when pronouncing the name of this city. Jorge A. Flores Ochoa confirms that these legends are repeated in the evening in all the families living in the neighborhood of Urubamba.

Expeditions for the purpose of looting, or official such as that of José María Pacheco in 1836 were conducted in the direction of the jungle, but almost always ended in tragedies. Thus, the belief persists : « all those who go to Paititi die, and consequently, the whole area is described as “forbidden”.

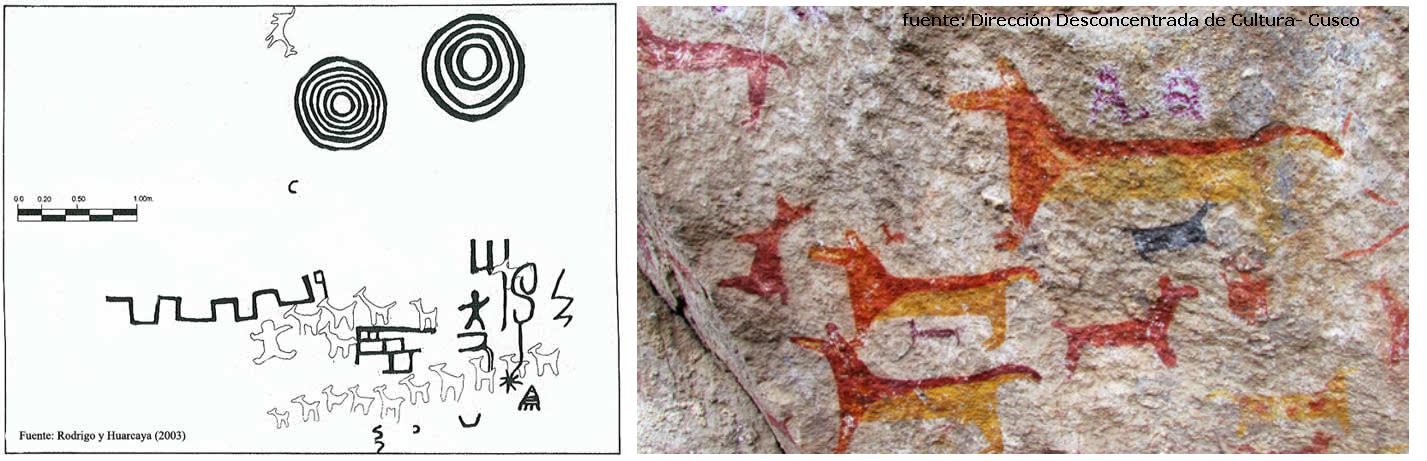

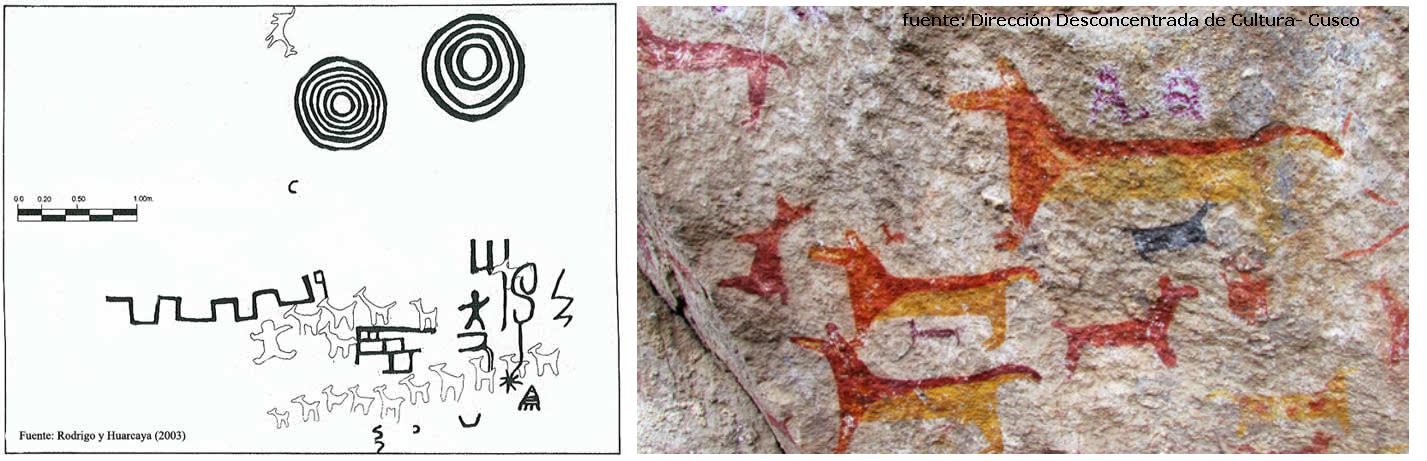

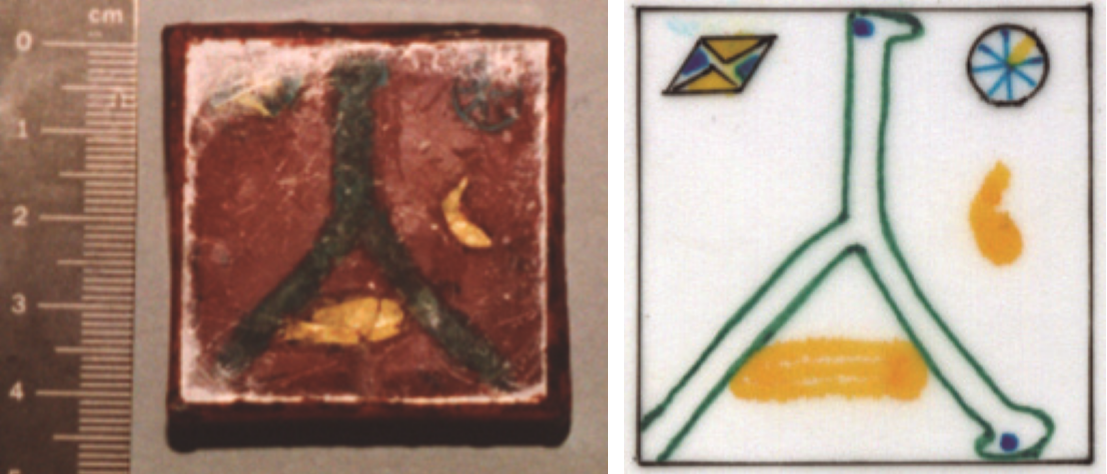

Father Polentini, who spent 20 years during the 70’s and 80’s in the immense province of Vilcabamba (today’s Convencion province), has also undertaken to gather and compile these testimonies in the northern province of Calca. In the latter, there are sites with engraved glyphs reputed to indicate the direction of Paititi, among others in Mantto (see the picture) on the Yavero River and near Honda Quebrada.

The most eloquent testimonies told by Father Polentini came from inhabitants of the remote valley of Larès / Lacco, a valley in which the archaeologist Thierry Jamin has for some ten years found several Inca sites and many forgotten paths. According to the religious, the time it took the Spaniards to chase Manco Inca was used to organize the exodus to Païtiti. Most of the groups would have left Ollantaytambo north of Cusco, and he describes quite precisely their journey as we shall see.

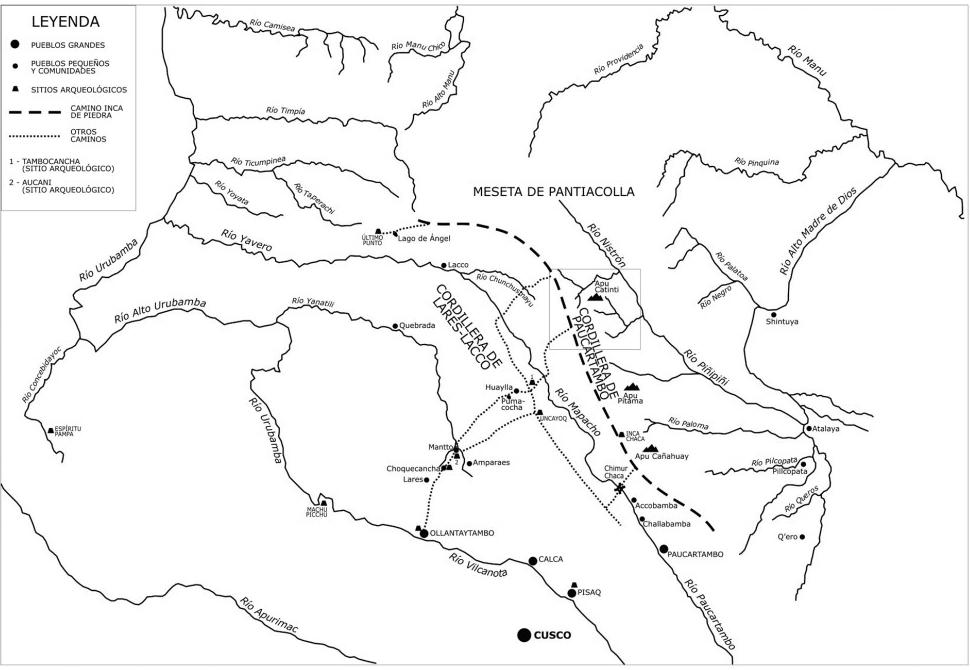

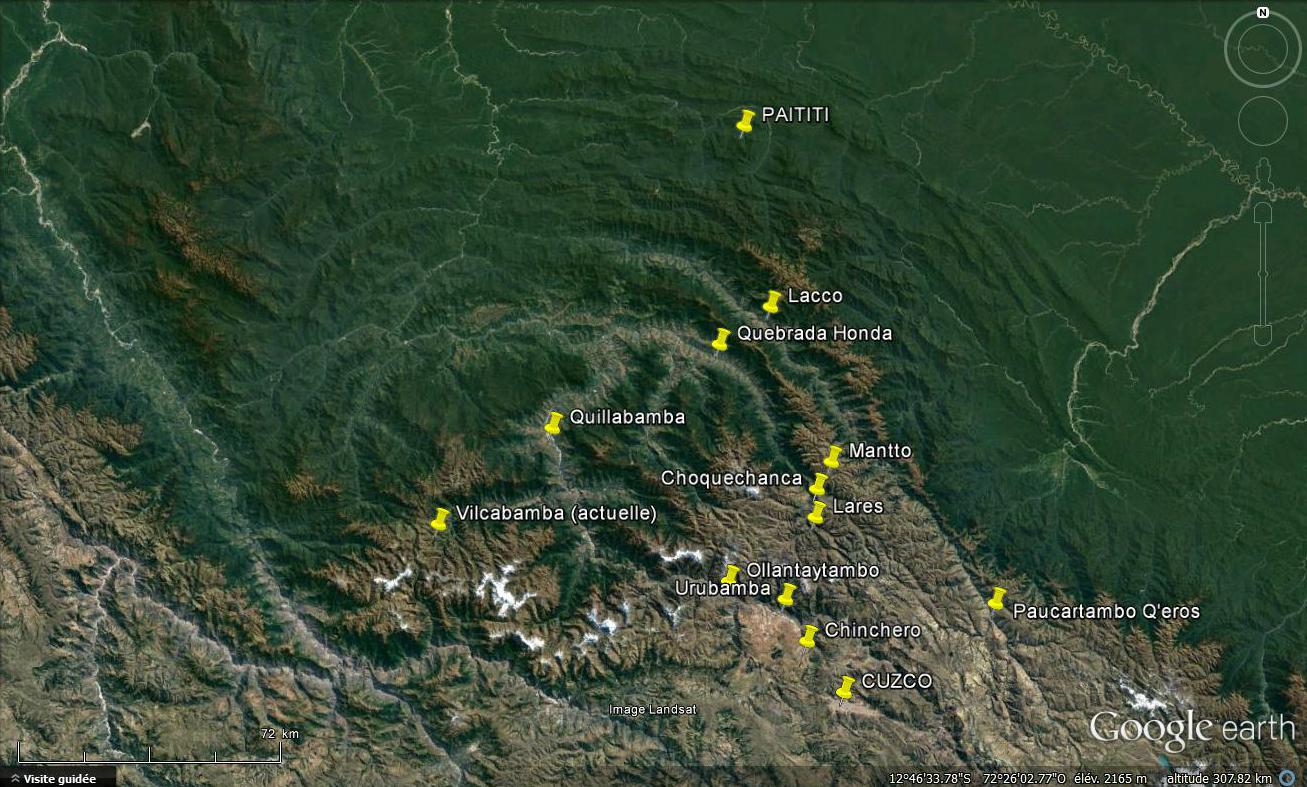

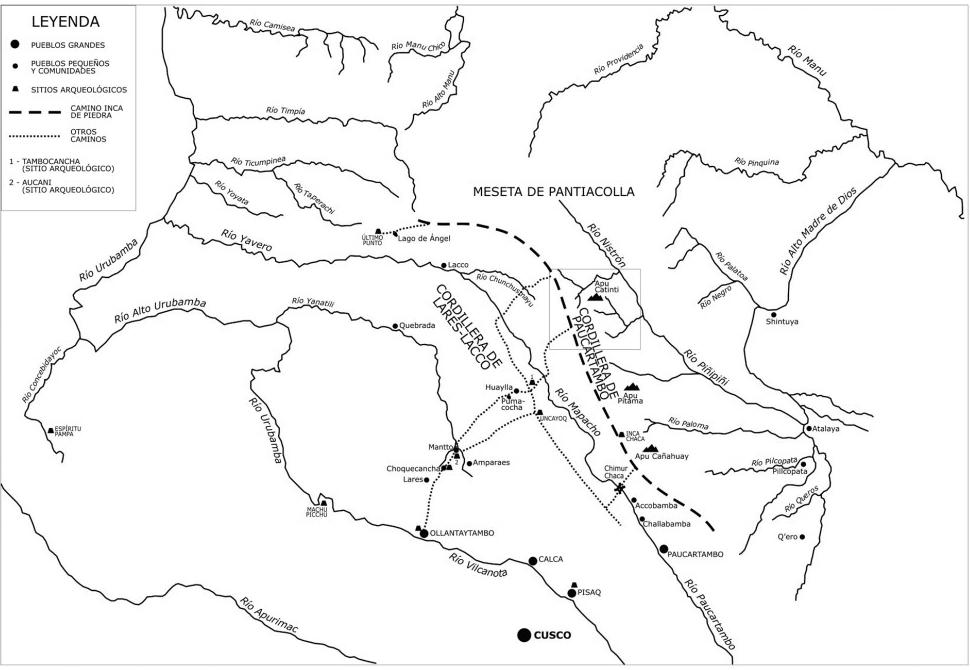

After listening all these testimonies, a small map is necessary. It would deserve a greater retreat to realize the extreme proximity of their areas of origin with the place where I found Paititi, but even so, we understands that the zone of the Inca empire where the legend of Paititi is the most present and precise is well north of Cusco:

Confirmation by the elements on the ground

As I have already said, the old ways speak, and their points of convergence are systematically synonymous with discoveries. Paititi localized, I sought, on the basis of the writings of some chroniclers describing the link between this city and Cusco, to find the necessary old ways that effectively enabled communication between these two great cultural, religious, commercial and settlement centers.

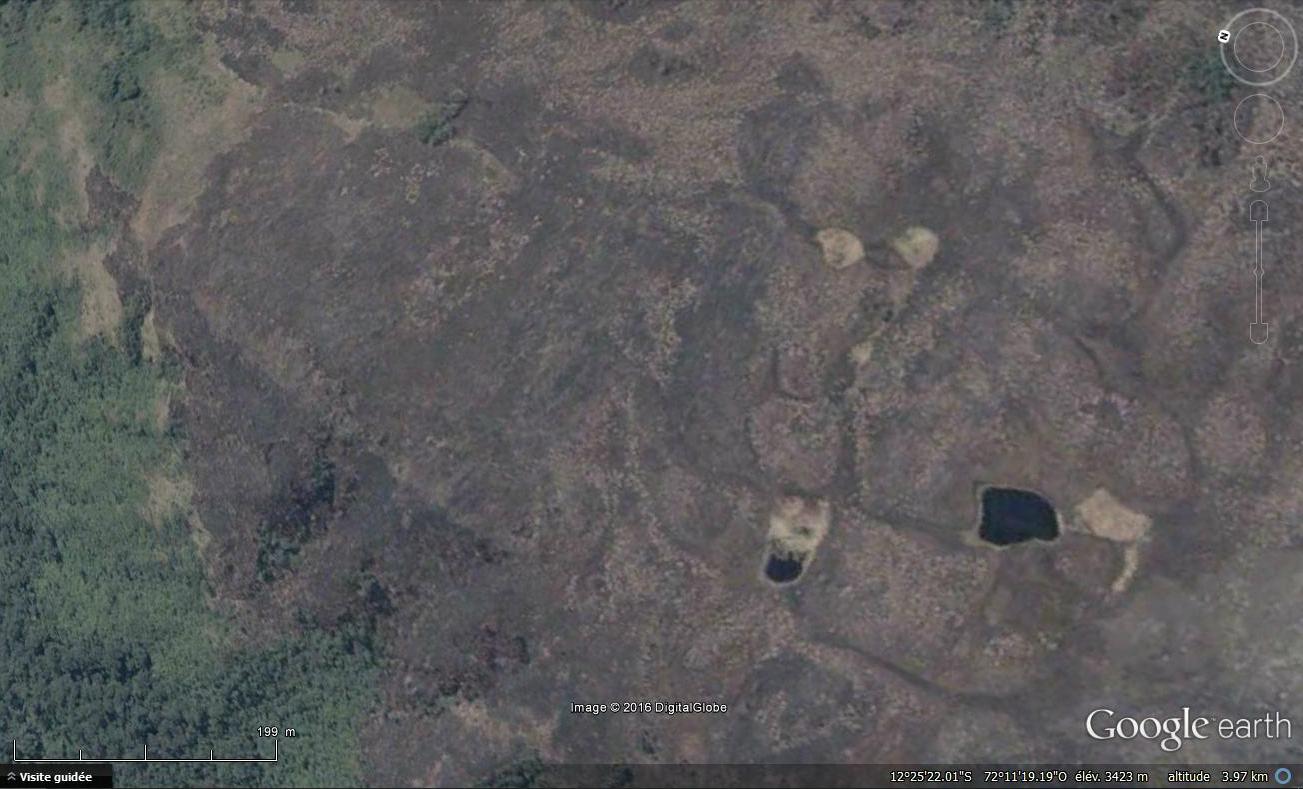

I started by looking for Google Earth on the still visible paths of ancient roads, and particularly on the end of the mountain range of Paucartambo, mountainous terrain located exactly between the two cities, and which I identified as the place where Vilcabalmba was Founded to help precisely this communication.

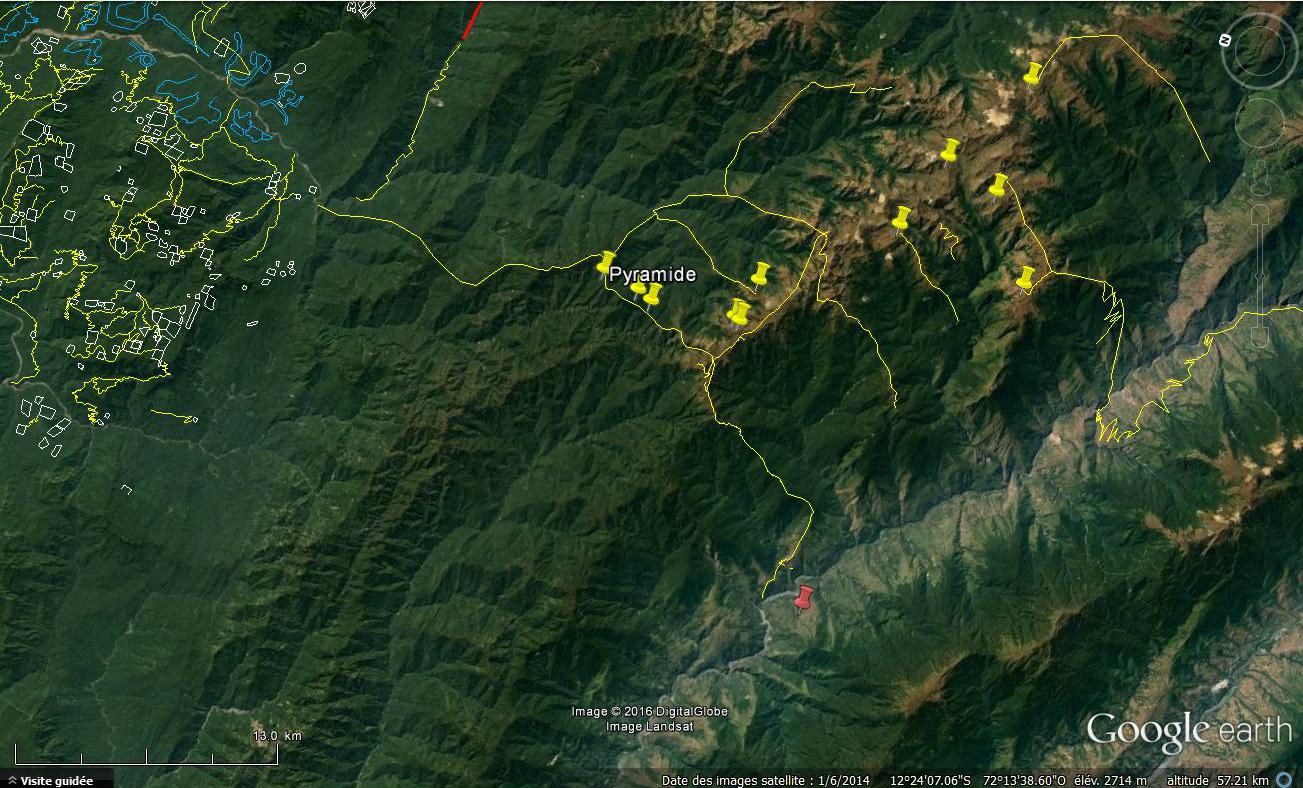

Here are the first results of my observations:

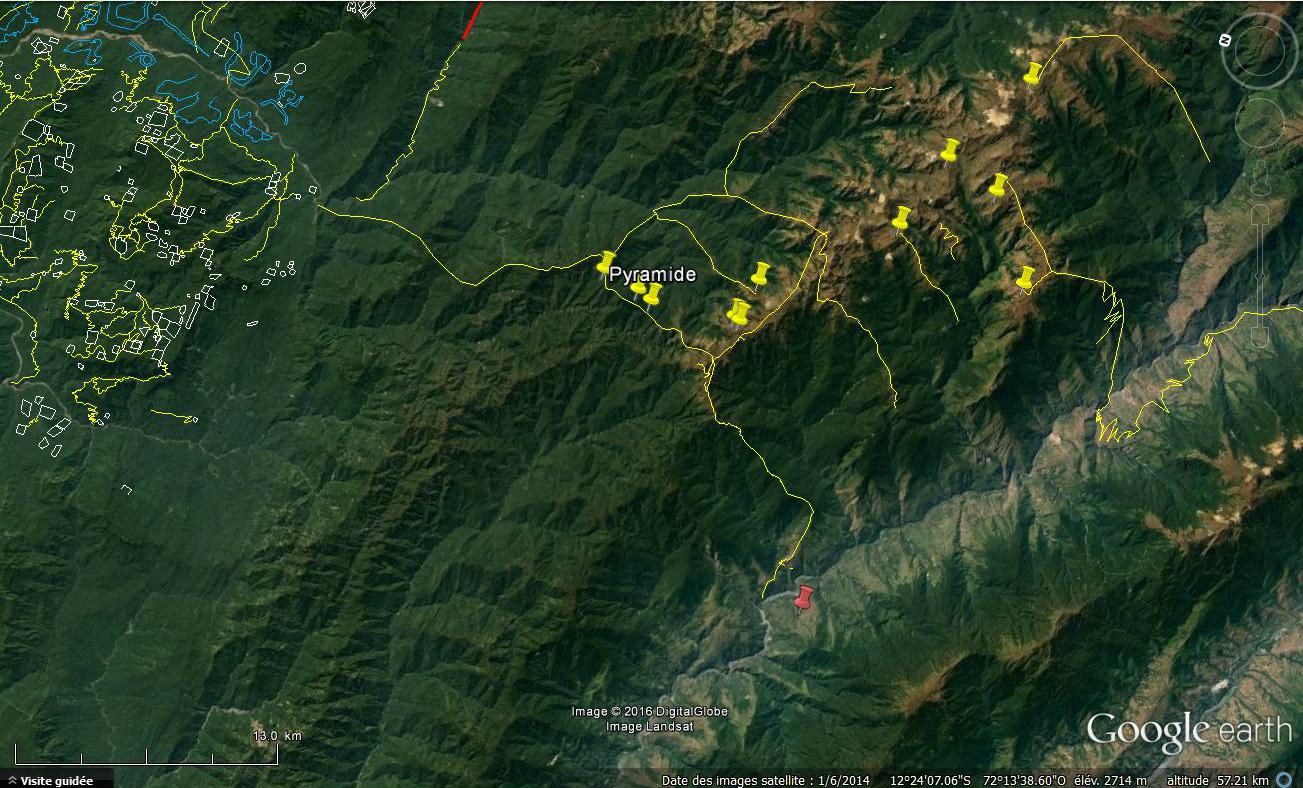

The point of departure of my discovery, the mountain face showing signs of development in platforms, is marked by the red mark. The first trail I found led to the pyramid, and further on to the “gate of the Amazon” and just behind to Paititi. I discovered other paths, inevitably old seen the very low frequentation of this zone, as well as several remarkable details that seem to be vestiges.

For example even if this time again the screenshots are quite bad :

I think that Vilcabamba the old one, witch was only a small town recently founded, a trading post in fact, was situated on this extreme part of the Cordillera. Having been burned down in 1572, this zone also could perhaps also correspond to it :

Vilcabamba, and thus Paititi, being supposed to be connected to Cusco by seven Tambos (reservoirs, storage places for merchandise and supplies for merchants and travelers).

So I searched the roads that linked this area to Cusco. Very soon however, I was faced with a problem: the closer I got to Cusco, the more the current roads multiplied. Even if experience shows that in the vast majority of cases the new ways are traced on the old ways, my research lost their interest.

This technique having reached its limits, and I then sought on the internet the route of the recognized paths of Inca origin on this famous cordillera of Paucartambo. The area is very poorly documented, and only the work of a few perspicacious archaeologists have allowed me to advance:

Gregory Deyermendjian, based on the work of Dr. Carlos Neuenschwander, identifies several ancient paths all known as “paths to Paititi” by the locals, including an amount on the Paucartambo cordillera from the west. It probably leaves Machu Pichu, then passes through Ollantaytambo, a fortified city from which the refugees from the Cusco region and the sacred valley would have left on their flight to Paititi, according to testimonies collected by Father Juan Carlos Polentini. The road passes through Choquechanca, where they would have stopped. Another is separated from it in Mantto, a site where the Incas had hidden part of their gold (according to Father Polentini) and where were found cave paintings representing large numbers of lamas, reputed to indicate the way to Paititi. It is interesting to note that according to legend, a caravan of 20,000 lamas laden with gold from all over the empire would have passed through the old Vilcabamba, which I think is located at the end of this mountain range.

This road then passes through the lake of Pumacocha where the fugitives would have thrown a part of their provisions after having lost several beasts of burden. Then, like all the roads described by Mr Deyermendjian, it joins a main road discovered by Dr. Neuenschwander.

This big road traverses the whole Cordillera of Paucartambo, and stops mysteriously without the archaeologists know where it leads. In some areas, it consists of khallki, or flat cobblestones; In others it is indicated only by deep furrows in the ground. It may be assumed that it originated in one way or another from Cusco, but its route is known only from Paucartambo, in the Q’eros territory. We recall their testimony, which describes precisely the flight of the Inkari (King Inca) carrying with him the Kero, ceremonial vase highly sacred in gold, towards the north.

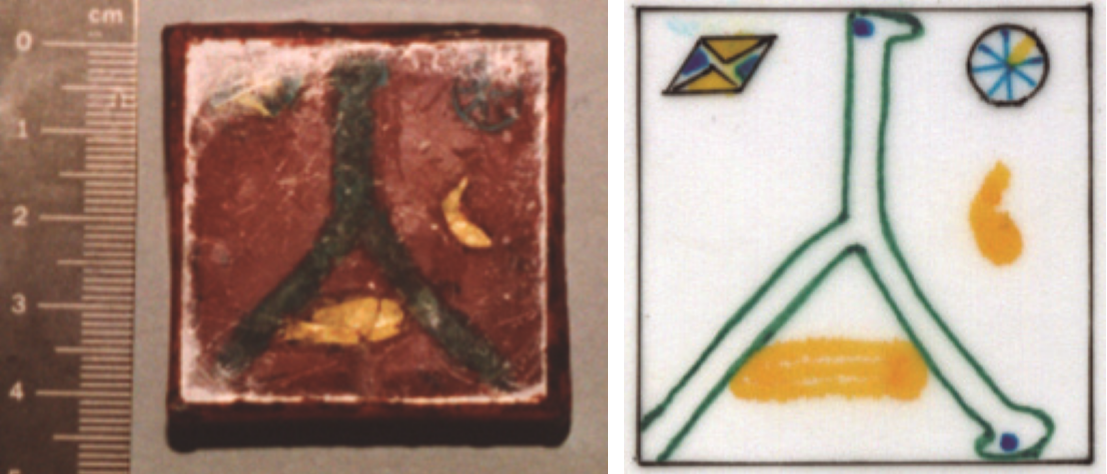

The main road is in fact oriented to the northwest and then due north to a point north of Cusco. Here we can mention the wax medallion which was attached to the manuscript Exsul Inmeritus by Blas Valera, the book by which I was able to locate Paititi. This medallion clearly indicates, in the form of a small compass, a north-easterly direction. According to Laura Laurencich’s interpretation, the specialist of this manuscript, it shows the location of Paytiti in relation to Cuzco: indeed, the tocapu of Cusco is present on one side.

This researcher, whose work is awesome, sees in the rudimentary map drawn on the medallion two rivers that meet and leave in this northeast direction. She analyzes the small rectangle formed by a gold paillette between these two converging arms as part of the tocapu of Paititi. I personally think that the medallion represents the two paths mentioned above, namely that which passes through Ollantaytambo on the left and the great track that starts from Paucartambo on the right, and that the gold rectangle is Cusco. The other tiny gold spangle, would be a landmark, actually the city of Mameria of which we will speak a little farther. The compass would be used to indicate the shortest and easiest route from Cusco: northeast direction, to find the main road to Challabamba, and finally to arrive at Paititi, a city witch is the principal subject in the book related to the medallion.

Let’s go back to the stone road: To quote Mr. Deyermendjian’s excellent field work, it starts from « Paucartambo and Challabamba, passes the village of Accobamba located in the valley of the Paucartambo-Mapacho river, near the jagged peaks of Apu Cañahuay. Further, in the section called Inca Chaca, the road is well paved. It passes there in the same north-north-west direction to reach the area known as Sondor (…) The road runs along the site of Collatambo, in the shadow of the summit of Huascar, and passes the known place As “Ñusta”, then the petroglyphs of the site called “Demarcation” or Huallpa Mayta, at a height of more than 4100 meters above the sea level zone, with high-relief figures of men and llamas at foot to the north. After passing Lake Suchi Cocha and the archaeological site Tambocasa, it follows the heights northwest and then north. It passes through the plains called Pampa de Maravillas and Mesa Pelada before reaching a very difficult transition zone, with a number of ravines, known as the Toporaque node. At the node are the “Toporaque houses” on the cold and wet plateau of Toporaque. It is an archaeological site of several structures, relatively well preserved, long and rectangular with low walls, suggesting a “headquarters” for the Inca soldiers who kept access to this strategic point. Low stone platforms are also visible. Here, the main road meets the cross road from the Lares-Lacco mountains, crossing the Chunchusmayu River in front of the ruins of Miraflores. (…) The stone road leaves the plateau of Toporaque, always towards the northwest, more and more visible, to enter a very high area of the cold plateau of Pantiacolla. There, the road is lost in a north-north-west direction in the tangled vegetation and a forest of dense clouds, in the upper reaches of the Timpia River … In this way, the supposed “Path of Paititi” which begins proudly, like the Qapaq Ñan, on the heights of Paucartambo, is lost in these remote and inhospitable corners of the Cordillera of Pantiacolla. ”

But in fact, it doesn’t.

It even leads directly, as its reputation claims, from Paucartambo to Paititi. Because the place where the main branch is lost is none other than the departure of the “isolated canyon” of the legend, which leads directly to the gate of the Amazon, and just behind, to the great city that I discovered , Paititi, bordered by the Rio Timpia. The main track in fact meets the path I first discovered, at the level of the pyramid 2km hardly further, and then about fifteen kilometers at the most via the crest, Paititi, which was once again masked by its hostile environment.

The route discovered by Dr. Carlos Neuenschwander was indeed the major sight that linked Cusco to Paititi. The existence of this developement, which has required so much effort to be elaborated, is for me a striking proof that my location of Paititi is definitely the right one.

Another very interesting fact in this large paved road : it is punctuated by tambos, these “reservoirs” mentioned in the texts referring to the foundation of Vilcabamba: following the failure of the military campaign of Tupac Yupanki and the peace treaty with the Yaya, great ancestor and lord of Paititi, Vilcabamba the old would have been built near Paititi, and connected to Cusco by one way and seven Tambos in order to facilitate trade with this city. Vilcabamba, or rather what remains of it after it was burnt, must necessarily be on the end of the Cordillera of Paucartambo or the beguining of the one of Pantiacolla as we have already seen, but also along this great route of communication linking Paititi to Cusco. By identifying the seven tambos which separate it from Cusco, we can definitely accredit the thesis of the location of Vilcabamba at the end of this cordillera. Paucartambo, Collatambo, Tambocasa, probably the knot of Toporaque, and …?

Another striking feature in studying the roads to Paititi described by Mr Deyermendjian, as well as the maps of other researchers interested in the area through which it was exported, is the extremely high number of archaeological remains bordering Paths. Aside from the “great” sites, steps and tambos already mentioned, they are: Aucani, Uncayoq, Tambocancha, the bridge of Chimur Chaka … It is also noted that the peaks of the Paucartambo mountain range are known as highly sacred: Apu Pitama, Apu Cañahuay …

Futhermore, if we refer to the testimony collected by the father Juan Carlos Polentini, Paititi would also be connected by land to Quito via Cajamarca. Shortly before the end of the route, G. Deyermendjian noticed a secondary road continuing its course on the ridge to the west, which could be that road, and would pass through platforms in the Rio Taperachi forest. Unless it follows the course of the Rio Yavero, along which have been found indicator glyphs.

Finally, “my” path, the one which get me to Paititi, taken in the direction of the descent, constitutes a third way which leads to this strange mountain to the large terraces that had attracted my attention in first. It then appears to pass into the neighboring valley at Chancamayo, and perhaps from thence to the sacred valley.

PS: Thank you for excusing the spelling mistakes and grammar errors in English

© Vincent Pélissier 2016

Confirmation by the Andean testimonials

It’s from the village of Paucartambo at the birth of the Cordillera of the same name, in the Q’eros people area that the anthropologists Oscar Nunez del Prado and Efrain Morote Best of the National University of Cusco collected the first version of the Q’eros Legend of Inkarri, the Inca King who sought refuge in Paititi, here supplemented by the information gathered later by Gregory Deyermendjian:

When the Spaniards arrived at Cusco, the Incas were killed and persecuted for their money and gold. Some fled to Ollantaytambo. The Inkari (the term designating the Incas kings by identifying them all with this mythical hero), who had founded the village of Q’ero and Cusco, again went through Q’ero fleeing to Païtiti, taking away the gold kero (Ceremonial vase ). He would have left the testimony of his passage in the form of prints which can still be seen in places called Mujirumi and Iñaki Yupin, which could be verified. It then followed an ancient road, a northern extension of the Qapaq Q’ero Ñan, towards Pantiacolla (or Pantay Qoya or Pantilla Qoya), a vast plateau of plains, mountains, streams and swollen rivers, foggy forests, extends far to the north in the middle of the lower jungle. They say that Inkarri stayed there for the rest of his days in the tropical oasis of “Païtiti” which is still hidden somewhere on the mysterious plateau.

The Q’eros are a completely atypical people: they were “discovered” by anthropologists only in 1955, still living totally isolated according to customs, language and Inca lifestyle, and it is still in mayor part the case today. What is incredible is that they occupy a territory located realy not so far to the northeast of Cusco: it says a lot about the secular inaccessibility and lack of knowledge on the area beyond …

Other testimonies on the existence of Paititi, coming from populations living all along this cordillera of Paucartambo are also very interesting:

In the area of Chinchero and Urubamba (crossing points between Cusco and Ollantaytambo), but also to the north still in the vicinity of Quillabamba and Vilcabamba (the present one), the locals firmly believe that Paititi was the refuge of the Incas , and some of them even claim that their ancestors were formerly communicating with Paititi without knowing exactly where this city was located in the jungle. Fernando Jorge Soto Roland who recorded these testimonies always emphasized the visible fear and the great respect of his sources when pronouncing the name of this city. Jorge A. Flores Ochoa confirms that these legends are repeated in the evening in all the families living in the neighborhood of Urubamba.

Expeditions for the purpose of looting, or official such as that of José María Pacheco in 1836 were conducted in the direction of the jungle, but almost always ended in tragedies. Thus, the belief persists : « all those who go to Paititi die, and consequently, the whole area is described as “forbidden”.

Father Polentini, who spent 20 years during the 70’s and 80’s in the immense province of Vilcabamba (today’s Convencion province), has also undertaken to gather and compile these testimonies in the northern province of Calca. In the latter, there are sites with engraved glyphs reputed to indicate the direction of Paititi, among others in Mantto (see the picture) on the Yavero River and near Honda Quebrada.

The most eloquent testimonies told by Father Polentini came from inhabitants of the remote valley of Larès / Lacco, a valley in which the archaeologist Thierry Jamin has for some ten years found several Inca sites and many forgotten paths. According to the religious, the time it took the Spaniards to chase Manco Inca was used to organize the exodus to Païtiti. Most of the groups would have left Ollantaytambo north of Cusco, and he describes quite precisely their journey as we shall see.

After listening all these testimonies, a small map is necessary. It would deserve a greater retreat to realize the extreme proximity of their areas of origin with the place where I found Paititi, but even so, we understands that the zone of the Inca empire where the legend of Paititi is the most present and precise is well north of Cusco:

Confirmation by the elements on the ground

As I have already said, the old ways speak, and their points of convergence are systematically synonymous with discoveries. Paititi localized, I sought, on the basis of the writings of some chroniclers describing the link between this city and Cusco, to find the necessary old ways that effectively enabled communication between these two great cultural, religious, commercial and settlement centers.

I started by looking for Google Earth on the still visible paths of ancient roads, and particularly on the end of the mountain range of Paucartambo, mountainous terrain located exactly between the two cities, and which I identified as the place where Vilcabalmba was Founded to help precisely this communication.

Here are the first results of my observations:

The point of departure of my discovery, the mountain face showing signs of development in platforms, is marked by the red mark. The first trail I found led to the pyramid, and further on to the “gate of the Amazon” and just behind to Paititi. I discovered other paths, inevitably old seen the very low frequentation of this zone, as well as several remarkable details that seem to be vestiges.

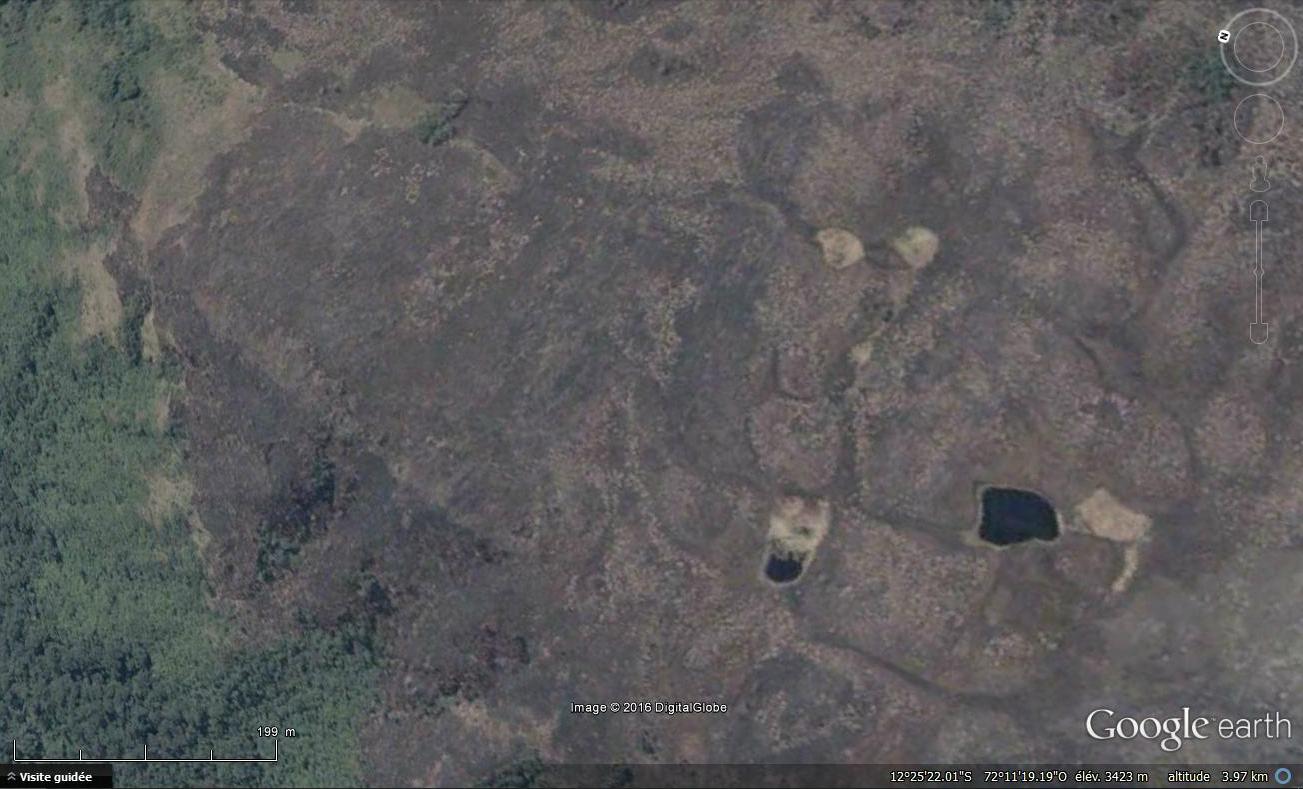

For example even if this time again the screenshots are quite bad :

I think that Vilcabamba the old one, witch was only a small town recently founded, a trading post in fact, was situated on this extreme part of the Cordillera. Having been burned down in 1572, this zone also could perhaps also correspond to it :

Vilcabamba, and thus Paititi, being supposed to be connected to Cusco by seven Tambos (reservoirs, storage places for merchandise and supplies for merchants and travelers).

So I searched the roads that linked this area to Cusco. Very soon however, I was faced with a problem: the closer I got to Cusco, the more the current roads multiplied. Even if experience shows that in the vast majority of cases the new ways are traced on the old ways, my research lost their interest.

This technique having reached its limits, and I then sought on the internet the route of the recognized paths of Inca origin on this famous cordillera of Paucartambo. The area is very poorly documented, and only the work of a few perspicacious archaeologists have allowed me to advance:

Gregory Deyermendjian, based on the work of Dr. Carlos Neuenschwander, identifies several ancient paths all known as “paths to Paititi” by the locals, including an amount on the Paucartambo cordillera from the west. It probably leaves Machu Pichu, then passes through Ollantaytambo, a fortified city from which the refugees from the Cusco region and the sacred valley would have left on their flight to Paititi, according to testimonies collected by Father Juan Carlos Polentini. The road passes through Choquechanca, where they would have stopped. Another is separated from it in Mantto, a site where the Incas had hidden part of their gold (according to Father Polentini) and where were found cave paintings representing large numbers of lamas, reputed to indicate the way to Paititi. It is interesting to note that according to legend, a caravan of 20,000 lamas laden with gold from all over the empire would have passed through the old Vilcabamba, which I think is located at the end of this mountain range.

This road then passes through the lake of Pumacocha where the fugitives would have thrown a part of their provisions after having lost several beasts of burden. Then, like all the roads described by Mr Deyermendjian, it joins a main road discovered by Dr. Neuenschwander.

This big road traverses the whole Cordillera of Paucartambo, and stops mysteriously without the archaeologists know where it leads. In some areas, it consists of khallki, or flat cobblestones; In others it is indicated only by deep furrows in the ground. It may be assumed that it originated in one way or another from Cusco, but its route is known only from Paucartambo, in the Q’eros territory. We recall their testimony, which describes precisely the flight of the Inkari (King Inca) carrying with him the Kero, ceremonial vase highly sacred in gold, towards the north.

The main road is in fact oriented to the northwest and then due north to a point north of Cusco. Here we can mention the wax medallion which was attached to the manuscript Exsul Inmeritus by Blas Valera, the book by which I was able to locate Paititi. This medallion clearly indicates, in the form of a small compass, a north-easterly direction. According to Laura Laurencich’s interpretation, the specialist of this manuscript, it shows the location of Paytiti in relation to Cuzco: indeed, the tocapu of Cusco is present on one side.

This researcher, whose work is awesome, sees in the rudimentary map drawn on the medallion two rivers that meet and leave in this northeast direction. She analyzes the small rectangle formed by a gold paillette between these two converging arms as part of the tocapu of Paititi. I personally think that the medallion represents the two paths mentioned above, namely that which passes through Ollantaytambo on the left and the great track that starts from Paucartambo on the right, and that the gold rectangle is Cusco. The other tiny gold spangle, would be a landmark, actually the city of Mameria of which we will speak a little farther. The compass would be used to indicate the shortest and easiest route from Cusco: northeast direction, to find the main road to Challabamba, and finally to arrive at Paititi, a city witch is the principal subject in the book related to the medallion.

Let’s go back to the stone road: To quote Mr. Deyermendjian’s excellent field work, it starts from « Paucartambo and Challabamba, passes the village of Accobamba located in the valley of the Paucartambo-Mapacho river, near the jagged peaks of Apu Cañahuay. Further, in the section called Inca Chaca, the road is well paved. It passes there in the same north-north-west direction to reach the area known as Sondor (…) The road runs along the site of Collatambo, in the shadow of the summit of Huascar, and passes the known place As “Ñusta”, then the petroglyphs of the site called “Demarcation” or Huallpa Mayta, at a height of more than 4100 meters above the sea level zone, with high-relief figures of men and llamas at foot to the north. After passing Lake Suchi Cocha and the archaeological site Tambocasa, it follows the heights northwest and then north. It passes through the plains called Pampa de Maravillas and Mesa Pelada before reaching a very difficult transition zone, with a number of ravines, known as the Toporaque node. At the node are the “Toporaque houses” on the cold and wet plateau of Toporaque. It is an archaeological site of several structures, relatively well preserved, long and rectangular with low walls, suggesting a “headquarters” for the Inca soldiers who kept access to this strategic point. Low stone platforms are also visible. Here, the main road meets the cross road from the Lares-Lacco mountains, crossing the Chunchusmayu River in front of the ruins of Miraflores. (…) The stone road leaves the plateau of Toporaque, always towards the northwest, more and more visible, to enter a very high area of the cold plateau of Pantiacolla. There, the road is lost in a north-north-west direction in the tangled vegetation and a forest of dense clouds, in the upper reaches of the Timpia River … In this way, the supposed “Path of Paititi” which begins proudly, like the Qapaq Ñan, on the heights of Paucartambo, is lost in these remote and inhospitable corners of the Cordillera of Pantiacolla. ”

But in fact, it doesn’t.

It even leads directly, as its reputation claims, from Paucartambo to Paititi. Because the place where the main branch is lost is none other than the departure of the “isolated canyon” of the legend, which leads directly to the gate of the Amazon, and just behind, to the great city that I discovered , Paititi, bordered by the Rio Timpia. The main track in fact meets the path I first discovered, at the level of the pyramid 2km hardly further, and then about fifteen kilometers at the most via the crest, Paititi, which was once again masked by its hostile environment.

The route discovered by Dr. Carlos Neuenschwander was indeed the major sight that linked Cusco to Paititi. The existence of this developement, which has required so much effort to be elaborated, is for me a striking proof that my location of Paititi is definitely the right one.

Another very interesting fact in this large paved road : it is punctuated by tambos, these “reservoirs” mentioned in the texts referring to the foundation of Vilcabamba: following the failure of the military campaign of Tupac Yupanki and the peace treaty with the Yaya, great ancestor and lord of Paititi, Vilcabamba the old would have been built near Paititi, and connected to Cusco by one way and seven Tambos in order to facilitate trade with this city. Vilcabamba, or rather what remains of it after it was burnt, must necessarily be on the end of the Cordillera of Paucartambo or the beguining of the one of Pantiacolla as we have already seen, but also along this great route of communication linking Paititi to Cusco. By identifying the seven tambos which separate it from Cusco, we can definitely accredit the thesis of the location of Vilcabamba at the end of this cordillera. Paucartambo, Collatambo, Tambocasa, probably the knot of Toporaque, and …?

Another striking feature in studying the roads to Paititi described by Mr Deyermendjian, as well as the maps of other researchers interested in the area through which it was exported, is the extremely high number of archaeological remains bordering Paths. Aside from the “great” sites, steps and tambos already mentioned, they are: Aucani, Uncayoq, Tambocancha, the bridge of Chimur Chaka … It is also noted that the peaks of the Paucartambo mountain range are known as highly sacred: Apu Pitama, Apu Cañahuay …

Futhermore, if we refer to the testimony collected by the father Juan Carlos Polentini, Paititi would also be connected by land to Quito via Cajamarca. Shortly before the end of the route, G. Deyermendjian noticed a secondary road continuing its course on the ridge to the west, which could be that road, and would pass through platforms in the Rio Taperachi forest. Unless it follows the course of the Rio Yavero, along which have been found indicator glyphs.

Finally, “my” path, the one which get me to Paititi, taken in the direction of the descent, constitutes a third way which leads to this strange mountain to the large terraces that had attracted my attention in first. It then appears to pass into the neighboring valley at Chancamayo, and perhaps from thence to the sacred valley.

PS: Thank you for excusing the spelling mistakes and grammar errors in English

© Vincent Pélissier 2016