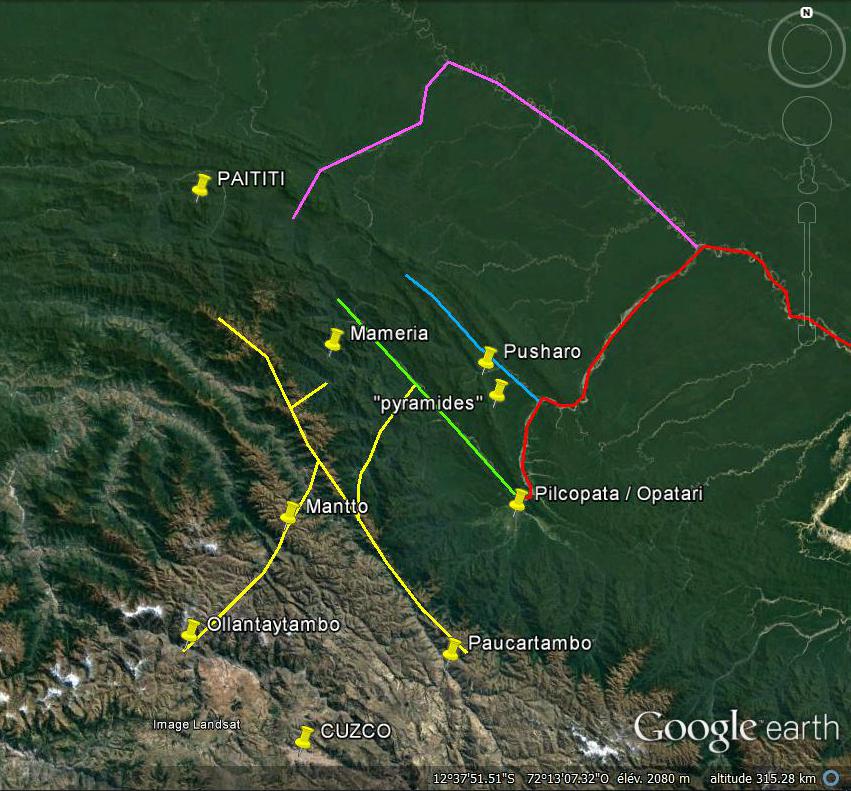

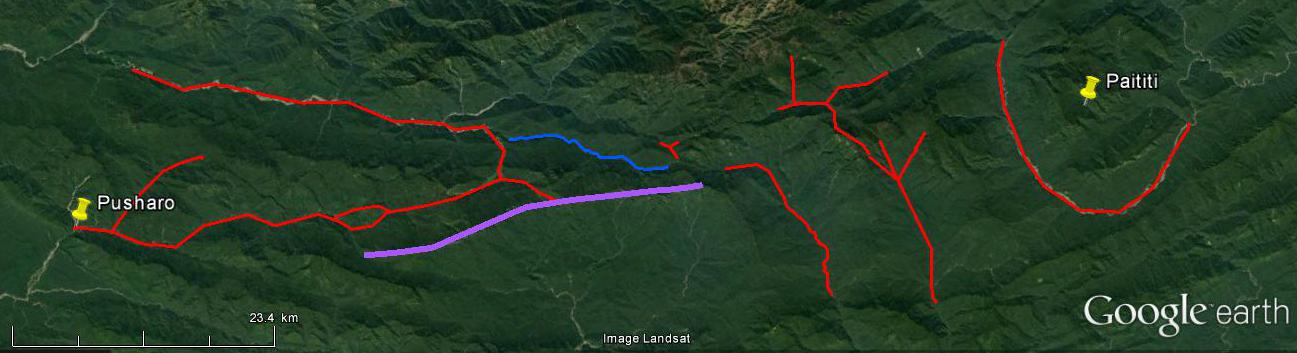

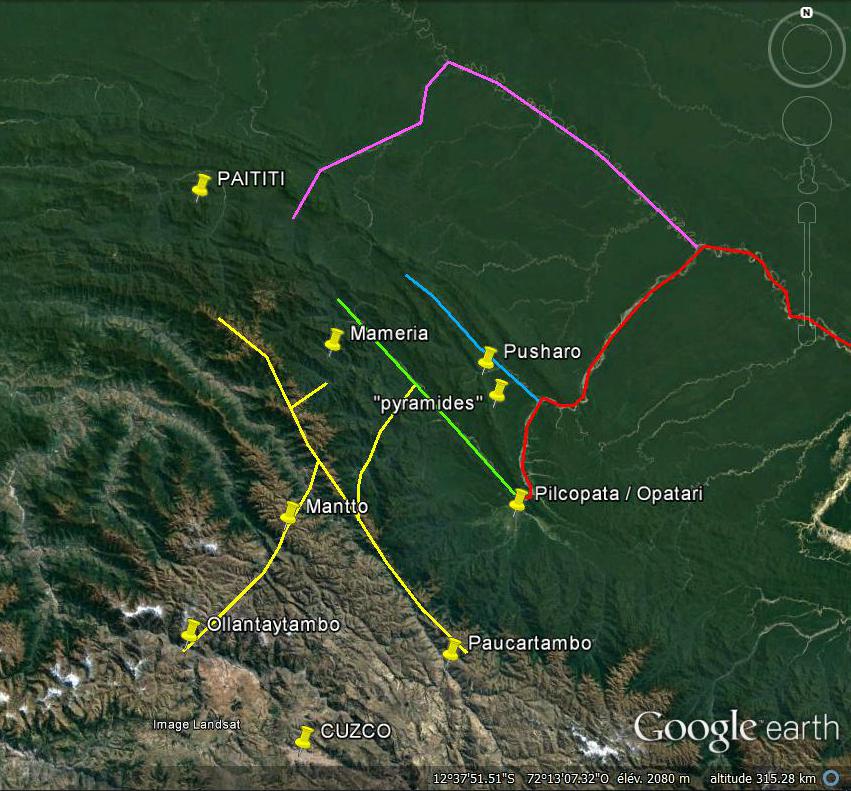

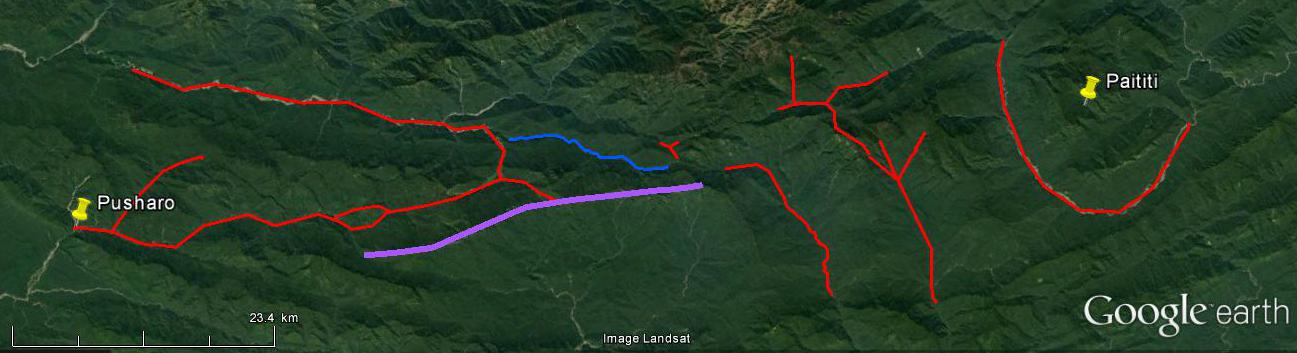

In red : Rio Madre de Dios

In purple : Rio Manu

In blue : Rio Pantiacolla

In green : Rio Nistron & Rio Pini Pini

In yellow : The main way and the inca paths we’ve seen

Confirmation by Amazonian testimonials

We will be interested here in the “Relacion de jornada y descubrimiento del rio Manu” that Juan Alvarez Maldonado left us after his exploration of the river Madre de Dios.

A fundamental precision is necessary: The Relacion de Maldonado, a priori very clear, has nevertheless been subject to extremely diverse interpretations , and therefore, for the most part, false. The whole problem arises from the point of departure: The narrative begins with “Twenty-five leagues to the east (in the river which it borrows) the river paucarguambo enter by the left, descending from minares where is the ynga.” 25 leagues to the east of what ? This is where the downside hurts: many eminent scholars, knowing that his expedition was initiated from Cusco, did not ask any more questions and assumed that the starting point of his narrative was the former Inca capital . It must be said in their defense that, to the east of the latter, there is a river which we now know as the Rio Paucartambo.

But the appearances are deceptive: the story of Maldonado actually begins at Pilcopata, and here’s why:

Paucartambo, the village or the current rio, is not at all 150km from Cuzco, not even half. It does not enter into any river to the east of Cusco, still less from the left because it flows from the south to the north of this city … Then for the Spaniards the Inca in 1569 was absolutely not in the south of Cusco at the sources of this rio, but completely on the other side to the north, to Vilcabamba official stronghold of resistance, no matter where it is located precisely. Finally, I defy anyone (to have myself plucked my hair for a moment there), to arrange in order the great rivers that come from right and left described throughout the story of Maldonado, and also the distances that separate them, even approximate, (and while keeping in mind that the author so precise in his narrative would not have forgotten an important tributary) with the reality of the basin of the Madre de Dios starting from Cusco.

No, the present Rio Paucartambo is definitely not the one mentioned in the Relation of Maldonado. And so the starting point of the story is not Cusco. It is also understood by studying how this expedition took place:

Viceroy Lope García de Castro appointed Juan Alvarez Maldonado as governor of an immense region ranging from Opatari (Inca citadel of the high Madre de Dios) to the North Sea 350 leagues to the east (Atlantic Ocean) and 120 leagues to the south, this excluding the territories of mojos reserved for the Spaniards of Santa-cruz. Thus, Maldonado, forbidden to travel like all other explorers to Mojos to find the treasures of the rumors, was the first European to explore the course of the river Madre de Dios.

In 1567 he organized his expedition from Cusco, bringing together a number of well-armed Spaniards and Indians. It reaches his lands through the village of Paucartambo, on the foothills of the Cordillera of the same name, and descends by the Rio Pilcopata, to its confluence with the rivers Tono and Coznipata (Piñi-Piñi), where he founded Santiago del Vierzo (present-day town of Pilcopata, fort Opatari inca).

He built many canoes made of balsa wood, and it was from this newly founded city that he rightly considered that his exploration of the unknown land of the “Rio Manu” began, because Opatari was known to the Spaniards, was the limite and start of his Government in the capitulations, and is situated at confluence of small rivers which form the beginning of a navigable river as he indicates.

He leaves in May 1559 to explore its new territory and to discover the countries of Paititi and Mojos. And twenty-five leagues further east … he sees entering in the rio on which he sails, by the left, the first important tributary : the rio Manu current. That he calls Paucarguambo. According to the researcher of Alfred Marston Tozzer (Harvard 1899), it is “impossible to doubt that the Paucarguambo designated is the Manu, because of the Relation it is deduced that this Rio Paucarguambo is in the immediate vicinity of a place called Manu- Pampa. It is very interesting to note that from then on, the rio on which Maldonado navigates suddenly changes name, and is called by the Indians the “Magno”. A misunderstanding on the part of the Spanish undoubtedly, a name that must be akin to “Manu”, and pronounced “mana-u”. This shows that for the Indians, the present Manu River was the source of the Madre de Dios, with which it formed one and the same entity.

It is also very interesting to note that in 1570 Maldonado wrote without blinking that the “Ynga” (the Inca) is at the sources of this rio. He probably believed that the rio was flowing from the Paucartambo range, making a wide detour through the jungle, and that is why he named it like he did. For the Indians we have seen, it was the rio Manu, name that it kept more downstream. For Maldonado, who thought, like all the Spaniards at the time, that the Inca in resistance was in Vilcabamba, and knew perfectly well that this city was on the Cordillera of Paucartambo, nothing shocking. Except that the Manu does not take its source in this cordillera, but in Paititi. Where was the Inca really, when he did not make diplomatic figuration in Vilcabamba. Starting from this, we can easily understand that the unfortunate Maldonado, probably here again misled by a translator with a deplorable accent, confused « minas », the mines, where is the Inca, a very Beautiful description and location of Paititi, with “Minaries”, the name of a tribe that never existed. Some will bring it closer to the Manaries indians, but these are cited later, without any fault. It remains a theory, but I smile imagining the Indian interpreter pronounce “minassss” dragging a little too … If he had understood the word, it would necessarily have fanned the covetous lust of the conquistador, and he would have up the Manu! I think that it was very lucky for Paititi not to be discovered on this occasion and wiped out like the rest of the empire by the Spaniards.

In any case, this confirms once again the location of Paititi, which is exactly at the sources of the Rio Paucartambo / Manu. Better still, it confirms that the Inca was well withdrawn. However, the misadventures of Maldonado do not stop there, and after passing to a hair of the fabulous city that he sought so much, he continued his journey:

« Fifty leagues farther enters (on the Magno rio) the river Cuchoa by the right which begins in the mountains of Peru in the Andes of Cuchoa, and in which at its entrance enter the rivers cayane, sangaban, and pule pule. Where the Cuchoa on entering is a sea. » We can perfectly recognize the current Rio Colorado, which on entering the Madre de Dios is indeed very wide. In passing we note that Maldonado did not record the entry by the right of the river Azul, either because it was not important enough, or because like today it entered the Madre de Dios at a place where this latter was divided into two, and the explorer has simply sailed on the other arm.

“Twenty leagues enters the river Guariguaca by the left, which is born in the province of yanagimes and boca negras” (The current rio de los Amigos) “eight leagues below by the right enters on the Magno the river Parabre which is born In the mountains of Carabaya “(Imambari nascenting in the cordillèra de Carabaya) “Twelve leagues enters the river Zamo by the right, by the back of the Toromonas, which is born in the territories of the Aravaonas” (Tambopata, this being confirmed by Brother Nicolás Armentia referring to the Franciscan writings of 1680 according to which the ” Religious order penetrated into the jungle at the level of Sandia at the sources of the Rio Tambopata, and arrived in Araonas territory.) “Thirty leagues below by the right enters the Omapalcas” (Heath, again the rio de las Piedras coming from the left was not seen because the Magno divides in two arms, one make a loop).

I doubt that Maldonado went further, I think he backed up and settled at the mouth of the Zamo, at the point now called “Puerto Maldonado”. Garcilazo mentions that the Indians welcome them at the beginning of their journey but change their attitude when they arrived at the Toromonas: Maldonado and two of his companions were captured. The Toromonas mentioned in La Relación reside well at the mouth of the river Zamo, and the Araonas or Aravaonas were upstream of this river, according to what is reported about them: on the right bank of the Madre de Dios and Forty leagues of the Cordillera of Peru is the province of the Aravaonas and more downstream is the province of the Toromonas … ” Maldonado heard of Paititi when it was retained by the Toromonas Indians and their cacique Tarano:

“There are immense plains fifteen leagues wide, to a high snowy ridge, which seems to be similar to that of Peru, according to the accounts of the Indians. The natives of the plains are called corocoros and those of the mountain called pamaynos. From this mountain they say that it is very rich in metals and is organized like a kingdom similar to that of Peru, with the same ceremonies (…) in the province of Paititi there are gold mines, silver and amber in large quantities. In the snowy cordillera there are many animals like those of Peru, but they are smaller. The natives are clothed in wool and also have crystal stones. ”

In fact, they well spoke to him of Peru … Plains of the Manu, the Cordillera of Pantiacolla, and behind, the snow-capped peaks of the Andes, unique on the continent. Mines he had missed. Of the Inca people who fled to Paititi with the “Ynga”. But Maldonado, in his exploratory euphoria and fantasies about the great emptiness that stretched before him à the east, did not for a moment contemplate that this city could be behind him.

Maldonado was liberated, but the other two, including his brother Simon, remained prisoners for two years. The conquistador returns to cusco to look for more men, but the month of november makes navigation difficult. Finaly, he survivors of the expedition emerged from the jungle south of Cusco near San Juan de oro, in the province of carabaya. At Cusco Maldonado was requisitioned to serve as camp chief during the campaign to subdue the so-called last capital of the resistance Vilcabamba, and during which he wrote this relationship in July 1572 to obtain permission to organize a second expedition. This will be refused to him by the viceroy, a decision of which there remains a letter in testimony, very unflattering to the conquistador judged to be incapable.

The name “Madre de Dios” would come from an exclamation that Maldonado would have uttered by seeing something that made him think of the holy virgin on a bank of the river. So it is after all perhaps she who, sickened by the atrocities committed in her name, saved Paititi.

The text of Maldonado, although somewhat forgotten for a time, definitely added to the confusion and mistakes of the Spaniards about Paititi. It is sometimes taken up by chroniclers who, by their interpretations, deform it a little more, leading to a further accentuation of the myth of a Paititi in the plains of Mojos, on the banks of the Mamoré, in the upper Guaporé, or completely lost in the heart of the continent of dense forest, at the end of the rio Madera …

Yellow : the main road on the cordillère of Paucartambo, and inca paths

Green : Rio Nistron & Rio Pini Pini

Blue : Rio Pantiacolla

Red : Rio Madre de Dios / Magno

Purple : Rio Manu / Paucarguambo

Fushia : Rio Colorado / Cuchoa

Orange : Rio de los Amigos / Guariguaca

Pink : Rio Imambari / Parabre

Turquoise : Rio Tambopata / Zamo

Dark blue : Rio Heath / Omacalpa

Other testimonies support the thesis of important access to Paititi by the Rio Manu :

Brother Juan de Odeja, in a letter of 1677 (taken up by Martua in 1906), reports that the Araonas and Toromonas had to pay a tribute to gold, silver, feathers and others to the Inca emperor. On their way to Cusco to do this, probably via the current province of Paucartambo, they saw a large Inca population who told them that the Ynga had been killed by the Spaniards, and that they fled to the Guarayos territory through a marshy plain in the backcountry, which in my opinion would be the basin of the present Manu. The Araonas reportedly said they saw in the lands of the Guarayos in question “Incas in a very large population, and in the middle the house of Apo, which they say is served with dishes of silver and gold and sitting on a bench in gold, and the walls inside the house of the idol are silver and gold that shines a lot. ”

The writings of Father Dominigo Alvarez de Toledo in 1661 (taken over by Brother Revello Bovo in 1848) tell us more about the location of these Guarayos at the time: the monk descended from the heights of Carabaya in the rainforest, changed its course and headed north, reaching the Toromonas, which occupied a large area between the Madidi and Madre de Dios rivers. He would have followed the same northerly direction, but we understand that he actually headed westwards, because he is heading a mission in the area of Paucartambo, and he says to us : “… Concerning the successor of the Inca who left Cusco of the Andes for the said town of Paititi, there is no doubt, because I joined the Nation of the Guarayos, who were those with whom he entered. ” This inevitably makes we think of the testimony of the Q’eros of Paucartambo.

In view of these testimonies, I therefore locate the lands of the Guarayos in the current province of Paucartambo. The area of Mameria, accessible by the Pini Pini, where the Apo (Apu) Catinti is the sacred summit, would be part of it, but apparently they can also reach their territory by making a detour through the interior, flat but marshy, the area of the Manu, which refers automatically to a people inhabiting Paititi. Which has also a sacred summit, as the drawing by Blas Valera shows.

Finally, how can we not mention among these testimonies that one the Jesuit father Andrés Lopez sends to Claude Acquaviva his superior in a letter discovered in 2001 by the researcher Mario Polia in the Vatican archives: At the beginning of the year 1576, four years after the death of Tupac Amaru, Father Andrés was appointed in the province of Willkapampa: Vilcabamba is the old one, since the Spaniards then knew its location, and therefore I presume that the province in question included at least the northern end of the cordillera de Paucartambo and the environs of Lacco, but also probably the lower jungle zone to the south of Pantiacolla, for according to Mario Polia, the priest reaches this area via “the Inca fort of Opatari” (Vargas Ugarte 1963) “in the land of the warrior Indians”, which clearly suggests the Antis / chuncos, or even to the fierce Guarayos evoked previously and located in this area. We have also seen that a road discovered by G. Deyermendjian ascended from the environs of Opatari on the Cordillera of Paucartambo, and led to Vilcabamba the old.

I think that was is on this occasion that, as the letter tells us, he converted a small Indian tribe who worshiped on his arrival a bezoar, a hard calculation forming in the belly of the cervidae, reputed to the four corners of the world for its medicinal properties. Having caused them to abandon this marvelous object for the Christian faith during the epidemic, Father Andres baptized them. Some of these new Christians, however, revolted by the exactions committed by the Spaniards, decided to flee to a kingdom “whose name is Paititi.” Father Andres offers one of them a crucifix, then a few months later he returns to Cusco where he has just been appointed Rector of the Jesuit Collège (November 1576), taking with him the Bezoar which he later gave to the Pope, delighted with this gift that he would sell a fortune …

Some time later in Cusco reappeared the three or four Indians who had fled. They then tell Father Andres an incredible story: When they arrived at the kingdom of Paititi, « whose king is very powerful, and governs with majesty a court similar to that of the great Turkish. His kingdom is very rich, adorned with gold, silver, and pearls in such quantities that they use them in kitchens for their pots and pans, as we use iron and other metals. » Having learned that they bore the representation of the god of the Christians, the curious king received them. When he saw the crucifix the sovereign laughed at them for a long time, and spat on it. It was then that, according to the Indians, a miracle occurred: the crucifix turned its head and cast tremendous looks around, causing the king and the whole court to prostrate for hours at the time. Convinced of the power of the god of the Christians, the king had a chapel built of gold and precious stones for the crucifix and adoration. He asked the Indians to put him in touch with someone who could teach him more about the Christian faith. This is how the Indians went to Cusco, where they meet Father Andrés.

It is then understandable that a meeting has happened, but it is not specified where. Cusco seems unlikely to me, so I think of Opatari. The King of Paititi was baptized by Father Andrés, but at that time “it pleased God to send him a fever that killed him.” Before he died, however, he promised the Jesuit priest to build a college and a church in massive gold, and ordered his only son and heir and the few nobles who accompanied them to introduce the Christian faith to Paititi. Father Andres reports all this to his Superior Father General during his trip to Rome in 1582, following which his Holiness the Pope decided to entrust to him the mission of evangelizing Paititi. But Father Andres lopez died on his return from Rome, at Hispanola (Cuba) in 1585. What happened to the mission? Marco Polia did not find any other information. However, a few years later, the secret Jesuit project to evangelize Paititi resurfaced, headed this time by Blas Valera, as we have seen.

From this incredible relationship we also draw some clues as to the location of Paititi: It would be situated « next to the Spanish province of Peru », which at the time stopped not far from Cusco in the Paucartambo range, and It is reached “within 10 days of walking”. This would correspond to the path through Opatari, where the Indians had to first look for Father Andrés, then climb the Pini-pini or the Rio Pantiacola, which is 200km in all, or 20km a day.

Confirmation by the elements on the ground

The concentration of sacred or utilitarian Inca and / or pre-Incas sites that we noted on the Andean side of Paititi is also found in the area of the other major access road to this city: the forest zone, and in particular, the southeastern end of the mountainous area of Pantiacolla.

We know that the Incas used this way of passage because Tupac Yupanki and his armies from Cusco established their base camp in Opatari (Pilcopata), which can be considered as the birthplace of the Madre De Dios. Going up from Pilcopata or Atalaya next to the river Piñipiñi and then its tributary the rio Nistron, we can run straight towards Paititi. If the rio does not reach it, we have access to the city by the valley to the east, little rugged.

This fluvial road between Paititi and Cusco seems to have been important. Unlike the parallel highway that we saw on the Paucartambo mountain range, everything indicates that the area around it was densely populated: the area of the sacred peak Apu Catinti in particular, was rich in discovery during the latter years. Among them, one of the most remarkable is the city of Mameria, unearthed in 1979 by Nicole and Herbert Cartagena, north of the peak. The sites of Choritia, Adumbaria, Chaku-Pangu, Niatene, Arete Perdido surround it and confirm the settlement. Currently, some Machiguengas are picking here coca leaves from seedlings that could be the wild descendants of those grown in ancient times. A path noticed by G. Deyermendjian seems to leave this area, and to go up the main track on the Paucartambo mountain range, passing through an inhospitable swamp and an abandoned tambo called San Martin.

It is also in the immediate vicinity to the north-east of this peak that Father Juan Carlos Polentini, based on the testimonies of the inhabitants of his parish and his own research, locates a rich gold mine discovered by Pachacutec during his journey in the province of Madre de Dios, and which would have been so productive that it would be largely responsible for the gold that covered the Kurikancha in Cusco. The exploitation would have occurred both in the open sky (gold being torn from the mountain by a waterfall) and digging the mountain. The ore would have been ferried by boat to the Nistron (maestron).

It is interesting to note that this thesis is accredited by another path discovered by Gregory Deyermenjian who notices that near the confluence of the Nistron and the Piñipiñi are important platforms, and that an other path connects this low zone and the main road. The path leads up to the summit of Llaqtapata where would have been an “Inca church”, some remains are visible, and by the Inca Tasquina site. It ascends the Rio Callanga along which there are circular vestiges, and climbs on Mount Callanga, where the researcher has noticed platforms “of an exceptional length”. Professor Salustio Gutierrez reports that the Inca fleeing the Spaniards would have used the word Kallankan to assure his people that sooner or later he would find the hidden city of Paititi (Gutierrez s / f and 1984). The path goes up finally in the forest by the western side of the Apu Pitama and joins the altiplano and the main way leading to Cusco.

Obviously, I do not think even just a moment that the assertion of Father Polentini, who likens this mine to Paititi, is the right one. According to him, it was at this point that the incas in flight would have surrendered, and there they would have hidden their sacred objects in gold. No, Paititi is farther to the north-east, as the so many solid proofs I give confirm. However, it is revealing that his local sources, to whom their ancestors had transmitted the idea for having worked, have told him about this site as Paititi.

Let us not forget that Paititi was a kingdom, and that it was above all known for its mineral wealth. The place being situated some sixty kilometers at most of the city, it is quite possible that it was part of its kingdom. This would probably place Mameria in his territory, or as an access.

Continue and end our tour of the access roads to Paititi, leaving from Opatari / Pilcopata to descend a little the Madre de Dios, then go up by its mouth the Rio Pantiacolla at our left. The latter is parallel to the Piñipiñi : like it, it rises high enough in the semi-mountainous and sylvestre massif, and likewise it takes its source not far from Paititi, to twenty kilometers at the most. Its path let me think that this was an important way of access to Paititi and communication of the latter with the plains of Mojos often mentioned as forming part of the “kingdom of the lord of Paititi”

Indeed, the Pantiacolla river has near its mouth a famous site, known as the “Paratoari pyramids”, which are actually only natural forms. However, it should be known that the Incas had a very special vision of the nature, the creations of the latter were intimately part of their space, and often they reworked them slightly to use or accentuate their sacred aspect. In the lagoons around these “pyramids” can be find hundreds of mysterious small pebbles carved in the form of hearts …

It is however from another well-known site, situated on a small tributary of this river, of which we will especially speak here:

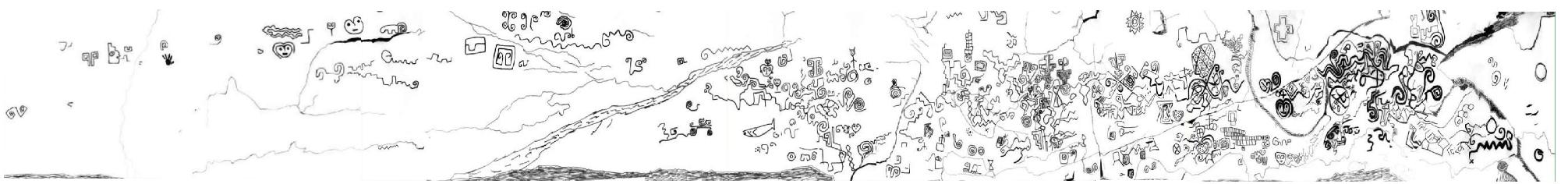

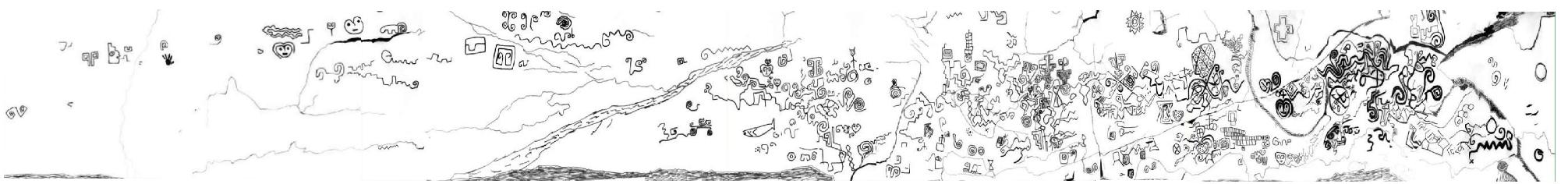

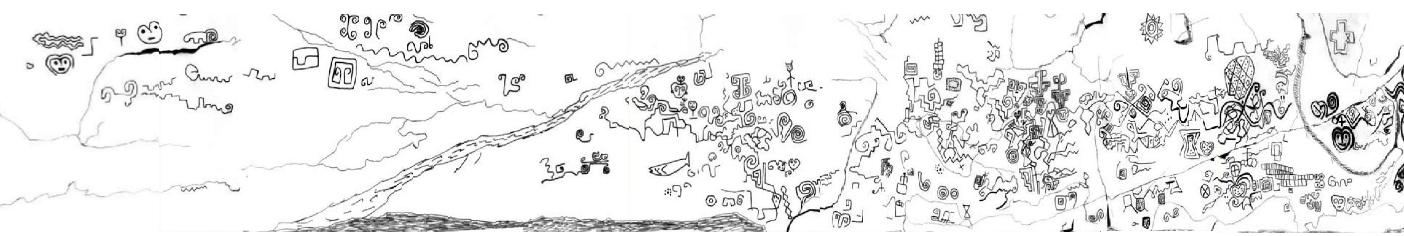

The fabulous engraved cliff of Pusharo. Actually, when I wrote the previous paragraph, two days ago, I never really looked at Pusharo’s famous petroglyphs. The many researchers who have been interested in these engraved signs have very divergent opinions: creation of Inca, pre-Incas or Amazonian peoples, astronomical or rather mythological representations, shamanic visions, writing in primitive tocapus, or genuine plan for travelers going to Paititi … For my part I had only observed them quickly, and they had appeared totally incomprehensible to me.

However, in light of my discovery of Paititi nearby, the theory that the carved cliff of Pusharo would be a map leading to this city appeared to me more and more likely, given its strategic location mentioned above. I had resigned myself to simply accrediting this thesis by mentioning the other cases of this type of “indicator” petroglyphs in the region, as in Pangoa or in Ocobamba.

I also found very interesting the fact that still at the beginning of the 20th century anthropologists could note that the Matsigenkas populating the zone came to color some lines supposed to represent rivers and paths with the aid of vegetable pigments which they also used for their paintings Rituals. If rivers and paths were among these petroglyphs, the whole was therefore necessarily a map, or at least a map blank. Placed there near the mouth of the Pantiacolla, it could only lead to Paititi.

The French archaeologist Thierry Jamin supports this thesis. Having visited the site several times, he even claims to have deciphered the symbols, and to have found Paititi by following this map. The problem is that the place where he thinks this city is located is not the right one. True, it is close, about 10km from “my” mountain, but it is on a different massif. Given all the elements I have gathered, and the extreme precision of the drawings of Blas Valera which represent only my mountain, I do not doubt my results. Thierry Jamin would have therefore left a good track, but to be mistaken somewhere, I had at least to try to understand why.

Without much hope, I then began to read everything I could find on Pusharo, and to try to understand something to the hundreds of symbols of the immense wall. I was going to give up because of the immense complexity of the thing when I remembered to have often found myself in the course of my research in the same disarray, and that each time the solution was in fact quite simple. So I started again: If the wall was addressed to the travelers coming sometimes from very far in the forest as well as to the refugees of the Inca empire, it had to be easily comprehensible. Points of reference such as rivers and mountains must have been included.

I was lucky to find what is, and by far, the best drawing made on this site. Its author is none other than Thierry Jamin, who published it on his site Pusharo.com. I wondered a lot about whether or not I should present it here. This wall is more than important, I have the right to study it as another, and I have deciphered it by my own means..

I would, however, have gladly refrained from disclosing my results here to leave him this honor. What drives me to use his work is that he made a mistake at the end of his reasoning, and therefore his result is wrong. If I publish my conclusions without treating this point, he will be the first to argue that I am wrong on the basis of those same drawing of the wall. In order to leave no doubt as to the accuracy of my discovery, and at the same time justify my questioning of his conclusions which may seem insolent, but which is only realistic, I will quote here a small part of his scientific work he published, in the form of this drawing.

However, I would like to bow to this researcher who was the first to understand the importance of this wall, and who is probably the best specialist of Paititi in the world. His expertise and his dedication to the cause of this city make him an indispensable asset for the future study of the site.

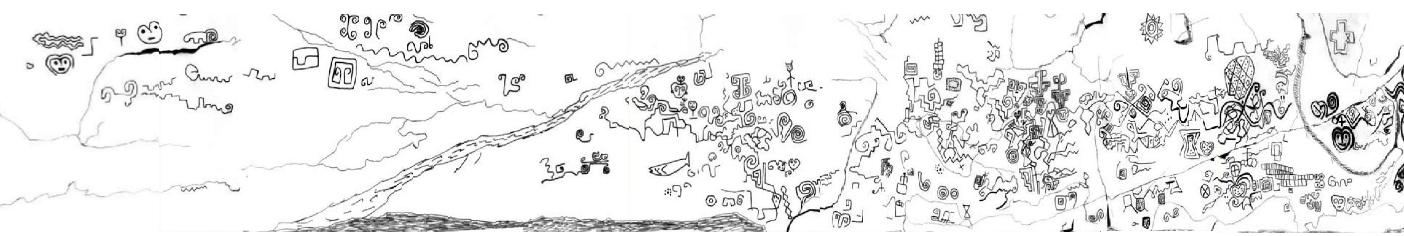

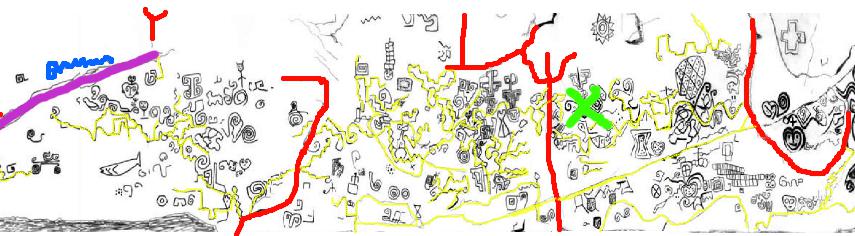

Thanks to his drawing, for the first time I could understand the true dimension of the site, and its true layout (over tens of meters) :

I have the advantage of knowing where Pusharo and Paititi are. In the perspective of a map, the concentration of important symbols on the right makes me think that it is Paititi. The wall being at Pusharo, it seemed to me probable that this point of departure is therefore situated on the left. And very quickly indeed, two symbols caught my attention:

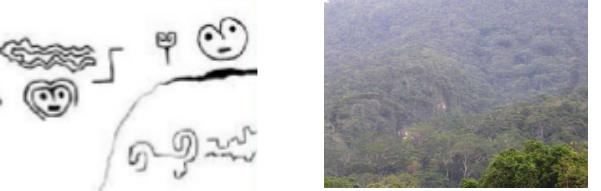

These are the two geoglyphs still observed by the same Thierry Jamin near the site of Pusharo, which locates this site on the map obviously for all travelers, whatever their language.

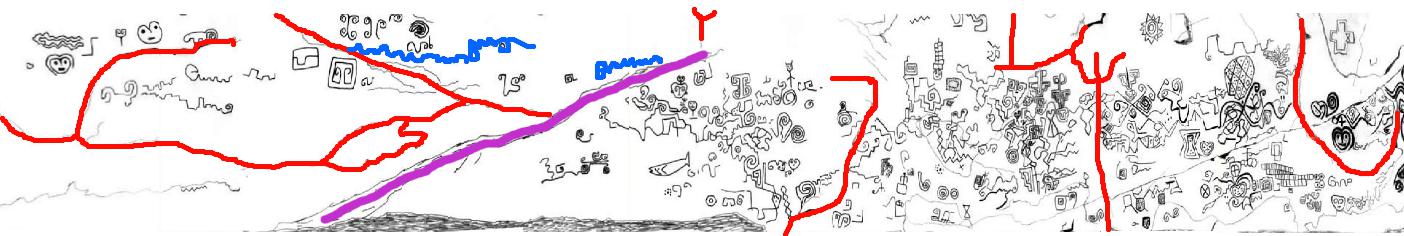

It is by observing that the right turn ending in the “cul de sac” present near these symbols corresponded perfectly to the river actually passing at the foot of the wall of Pusharo on Google Earth that I understood one thing paramount : the lines Which enamel the wall are not, as I thought until then, the faults of the rock, but they represent the rivers and / or roads, the famous geographical landmarks I was looking for. Could it be that simple? I forgot the dozens of symbols, and repassed these lines in red. I was amazed at the correspondence I could see:

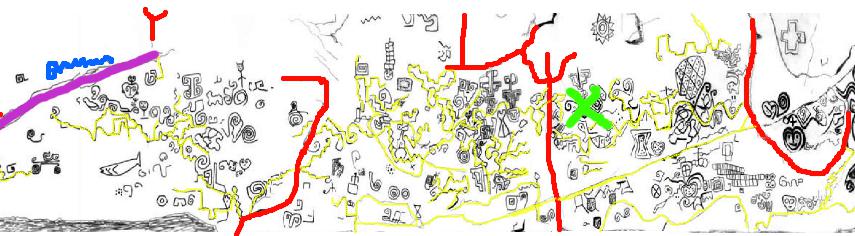

Absolutely ALL is there. And with remarkable precision. It is so precise that I will dispense with comments on the course of the main rivers (red) which are obviously also paths, for otherwise they are represented by a spiral followed by small waves (blue). A large rocky bar, which forms an important cliff along its entire length, is indicated by a big plot (purple)

The small red “Y” corresponds in fact to the meeting point of three roads : one coming from the end of the Cordillera de Paucartambo where we saw Vilcabamba was, one coming from the “gate” of the Amazon as I called it at the beginning of my researches, and therefore at Paititi, the last branch points down, towards what suddenly resembles seeing the wall of Pusharo, as the suburb of a city still more immense than what I thought. Look at the distances … The bulk of the site, which begins two-thirds of the cliff, is in all 50km long …

With a closer look, in fact even the small roads that allow traffic in the neighborhoods are detailed. Having become quite good to find the old roads and fields or traces of buildings on Google Earth despite the vegetation, (in fact the old version of this software 7.0.2.8415 is better to find it, because of an ancient sattelite view in low quality) this fabulous map enabled me to identify hundreds of them on the ground, in just a few hours , which suggests that there are many others.

All the paths that I have found are still thought of in a very logical way: they generally follow the curves of the terrain so as not to have to go up and down, because the relief, which does not seem enormous from this satellite point of view , Is actually rather undulating. Some paths, however, inevitably climb, zigzagging.

Looking for the paths, I realized that many of the engraved elements were not theoretical symbols, but a description of the reality on the ground: thus the many small staircases are nothing but the ascending paths, which ascend in a zigzag pattern. The many spirals must also have a meaning of the same type that I still have difficulty identifying but which I think I discover by spending a little more time studying the terrain.

The big “X” also corresponds to a reality on the ground: on a large cliff, two enormous faults form an “X” quite identical, very visible from the paths, and therefore an excellent landmark.

Having found a concentration of large platforms at the top of the neighboring mountain of Paititi, very high and imposing, I think that the oval divided into small diamonds with points indicates a very important fortress given the strategically strategic location, hardly accessible. The diamonds and points would give indications on the garrison. But this is only a hypothesis.

Other symbols seem to represent units of account, demographic perhaps, but I think also agricultural. Indeed on the drawing of Blas Valera, on this side opposite to the dam, we can discern a corn plant, and this aspect is found in what Diego Alemán heard about Paititi. The structures that I have found since the beginning, for the most part, seem by in their dimensions to correspond more to walls surrounding fields or flocks than to buildings. However, I found in a book by Fernando Santos Granero the trace of a relationship of Martín Hurtado de Arbieto who, starting from Huánuco in the north enters the forest and discovers an astonishing building … 525 meters wide, with 20 doors, where Matsisgenkas resided.

Finally, it seems almost certain that the rest of the symbols represent either buildings or human groups (clans, ethnic groups, chiefdoms) given their distribution in what resembles residential neighborhoods served by roads.

As with the Jesuit card representing the Madre de Dios, by observing the incredible correspondence of the engravings with the view of the sky, we can wonder how did the incas did it… In fact, here this is explainable : most of the roads and buildings are built on a more or less abrupt rock face. The same goes for rivers, which are actually torrents. So that seen from below, we had to have a vision close enough to what is represented. Maybe it was the same for the basin of the Madre de Dios, seen from the top of the Cordillera of Paucartambo.

It would be offensive to the cartographic genius of the inhabitants of Paititi to summarize their art to this, for there is nevertheless a real will to conceptualize the terrain and elevate the point of view, especially to the left of the map, but you must understand that this idea is extremely important for the future.

Let us now turn to what interests us at first: I have voluntarily set aside the representation of Paititi, here it is :

It is only by knowing Paititi that we can really understand this drawing. Indeed, if we continues to read the map as before, seen from the sky, the earth surrounded by water (the mountain with the five peaks) seems to be only slightly densely populated, the essential symbols appearing to be located beyond at the right. This is exactly what Thierry Jamin had to think.

Knowing Paititi perfectly, and the location of the sacred enclosures drawn by Blas Valera, necessarily synonymous with the heart of the city, I had a different point of view. For the sake of realism, I think that the first engravers of Pusharo represented this loop formed by the river on the scale and in the same style as the rest of the fresco, seen from the sky. But that was a problem. I remembered being a child, drawing a bubble with a pen to make a character speak, and then realizing that I had absolutely no place to write everything I wanted to make him say. This is exactly what happened: the very important symbols that had to appear on the site of Paititi overflowed. It is thus that we finds the profile face of the Grand Ancestor (yaya, gran candire, white king, etc …) or the Inca according to the paternity of the fresco, outside the loop representing the river, thus appearing to be situated on the mountain next door. On the one where Thierry Jamin hopes to find Paititi.

We can understand everithing while remembering that the more the map advances, the more the engravers have represented slopes of populated mountains seen from below, and not from an aerial view. This evolution reaches its climax at the end of the fresco at Paititi: Indeed, an important line, which has nothing to do with reality on the ground, contrary to all others, represents the crest of the mountain with five summits from below. In order to make the traveler understand that it is actually the center of the loop formed by the river, its trail begins in the loop, but it exceeds.

Above all, we can see that on the right is the valley which separates our mountain with five summits from the neighboring mountain: the steep promontory formed by the latter is clearly identifiable. Thierry Jamin, although the authorization he has been waiting for years is finally granted, will not find Paititi on this promontory, which has no symbol.

Here. We can even see one of these spirals joined to a series of small waves (lower right) but much more accentuated than the rivers mentioned above, and which is exactly at the right location to represent the reservoir of artificial water we considered . A strange little “x” crosses it, which lets me think that it tells the travelers the beginning of the “path paved with black stones” which constitutes the main access to the upper city, from this lagoon precisely. I tried to find a fairly close view on Google Earth, but it’s complicated:

Interestingly, the geoglyphs that appear to be everywhere on the Pusharo wall do not include any of the 12 large specimens surrounding Paititi from Blas Valera’s drawing, which makes me think that the Pusharo fresco must be prior to their realization. Concerning the other mysterious symbols that dot this face of my plateau … And this cross at the top of the wall, I confess that I do not understand anything yet, but with a little time who knows …

An overview of my discovery:

I think it would be very interesting to dig at the foot of the Pusharo wall. Indeed, the river that borders it, following its many floods, has buried the bottom of this wall under several meters of silt, as evidenced by the reports of the first observers of the site. Perhaps other occupied sites, located to the north on the upper basin of the Manu, were indicated.

Conclusion

We can conclude from paths and evidences presented that the testimonies and rumors that are transmitted from generation to generation in the provinces north of Cusco are based.

After centuries of fruitless research, academic negations, mockery of those who believed in the last refuge of the Incas who had survived there for a certain period, I think I can affirm that I have discovered the mythical city of Paititi.

My work proves in a certain way the existence of this city, by various reasonings valid independently of each other, and all based on data from the field or documents of time. I thus discovered the precise location of Paititi, and more, gives a relatively complete plan of Paititi. By publishing this information Me, Vincent Pélissier, hope to advance the science, and thinks I am worthy, by the precision and seriousness of my work, to be recognized as the inventor of this site.

The decision to publish the result of my work was not taken with gaiety of heart, I even did everything to avoid this. I am aware that it will have important consequences. The attached document is intended to explain what circumstances forced me to publish my discovery.

Vincent Pélissier 2016

PS: Thank you for excusing the spelling mistakes and grammar errors in English

© Vincent Pélissier 2016

In red : Rio Madre de Dios

In purple : Rio Manu

In blue : Rio Pantiacolla

In green : Rio Nistron & Rio Pini Pini

In yellow : The main way and the inca paths we’ve seen

Confirmation by Amazonian testimonials

We will be interested here in the “Relacion de jornada y descubrimiento del rio Manu” that Juan Alvarez Maldonado left us after his exploration of the river Madre de Dios.

A fundamental precision is necessary: The Relacion de Maldonado, a priori very clear, has nevertheless been subject to extremely diverse interpretations , and therefore, for the most part, false. The whole problem arises from the point of departure: The narrative begins with “Twenty-five leagues to the east (in the river which it borrows) the river paucarguambo enter by the left, descending from minares where is the ynga.” 25 leagues to the east of what ? This is where the downside hurts: many eminent scholars, knowing that his expedition was initiated from Cusco, did not ask any more questions and assumed that the starting point of his narrative was the former Inca capital . It must be said in their defense that, to the east of the latter, there is a river which we now know as the Rio Paucartambo.

But the appearances are deceptive: the story of Maldonado actually begins at Pilcopata, and here’s why:

Paucartambo, the village or the current rio, is not at all 150km from Cuzco, not even half. It does not enter into any river to the east of Cusco, still less from the left because it flows from the south to the north of this city … Then for the Spaniards the Inca in 1569 was absolutely not in the south of Cusco at the sources of this rio, but completely on the other side to the north, to Vilcabamba official stronghold of resistance, no matter where it is located precisely. Finally, I defy anyone (to have myself plucked my hair for a moment there), to arrange in order the great rivers that come from right and left described throughout the story of Maldonado, and also the distances that separate them, even approximate, (and while keeping in mind that the author so precise in his narrative would not have forgotten an important tributary) with the reality of the basin of the Madre de Dios starting from Cusco.

No, the present Rio Paucartambo is definitely not the one mentioned in the Relation of Maldonado. And so the starting point of the story is not Cusco. It is also understood by studying how this expedition took place:

Viceroy Lope García de Castro appointed Juan Alvarez Maldonado as governor of an immense region ranging from Opatari (Inca citadel of the high Madre de Dios) to the North Sea 350 leagues to the east (Atlantic Ocean) and 120 leagues to the south, this excluding the territories of mojos reserved for the Spaniards of Santa-cruz. Thus, Maldonado, forbidden to travel like all other explorers to Mojos to find the treasures of the rumors, was the first European to explore the course of the river Madre de Dios.

In 1567 he organized his expedition from Cusco, bringing together a number of well-armed Spaniards and Indians. It reaches his lands through the village of Paucartambo, on the foothills of the Cordillera of the same name, and descends by the Rio Pilcopata, to its confluence with the rivers Tono and Coznipata (Piñi-Piñi), where he founded Santiago del Vierzo (present-day town of Pilcopata, fort Opatari inca).

He built many canoes made of balsa wood, and it was from this newly founded city that he rightly considered that his exploration of the unknown land of the “Rio Manu” began, because Opatari was known to the Spaniards, was the limite and start of his Government in the capitulations, and is situated at confluence of small rivers which form the beginning of a navigable river as he indicates.

He leaves in May 1559 to explore its new territory and to discover the countries of Paititi and Mojos. And twenty-five leagues further east … he sees entering in the rio on which he sails, by the left, the first important tributary : the rio Manu current. That he calls Paucarguambo. According to the researcher of Alfred Marston Tozzer (Harvard 1899), it is “impossible to doubt that the Paucarguambo designated is the Manu, because of the Relation it is deduced that this Rio Paucarguambo is in the immediate vicinity of a place called Manu- Pampa. It is very interesting to note that from then on, the rio on which Maldonado navigates suddenly changes name, and is called by the Indians the “Magno”. A misunderstanding on the part of the Spanish undoubtedly, a name that must be akin to “Manu”, and pronounced “mana-u”. This shows that for the Indians, the present Manu River was the source of the Madre de Dios, with which it formed one and the same entity.

It is also very interesting to note that in 1570 Maldonado wrote without blinking that the “Ynga” (the Inca) is at the sources of this rio. He probably believed that the rio was flowing from the Paucartambo range, making a wide detour through the jungle, and that is why he named it like he did. For the Indians we have seen, it was the rio Manu, name that it kept more downstream. For Maldonado, who thought, like all the Spaniards at the time, that the Inca in resistance was in Vilcabamba, and knew perfectly well that this city was on the Cordillera of Paucartambo, nothing shocking. Except that the Manu does not take its source in this cordillera, but in Paititi. Where was the Inca really, when he did not make diplomatic figuration in Vilcabamba. Starting from this, we can easily understand that the unfortunate Maldonado, probably here again misled by a translator with a deplorable accent, confused « minas », the mines, where is the Inca, a very Beautiful description and location of Paititi, with “Minaries”, the name of a tribe that never existed. Some will bring it closer to the Manaries indians, but these are cited later, without any fault. It remains a theory, but I smile imagining the Indian interpreter pronounce “minassss” dragging a little too … If he had understood the word, it would necessarily have fanned the covetous lust of the conquistador, and he would have up the Manu! I think that it was very lucky for Paititi not to be discovered on this occasion and wiped out like the rest of the empire by the Spaniards.

In any case, this confirms once again the location of Paititi, which is exactly at the sources of the Rio Paucartambo / Manu. Better still, it confirms that the Inca was well withdrawn. However, the misadventures of Maldonado do not stop there, and after passing to a hair of the fabulous city that he sought so much, he continued his journey:

« Fifty leagues farther enters (on the Magno rio) the river Cuchoa by the right which begins in the mountains of Peru in the Andes of Cuchoa, and in which at its entrance enter the rivers cayane, sangaban, and pule pule. Where the Cuchoa on entering is a sea. » We can perfectly recognize the current Rio Colorado, which on entering the Madre de Dios is indeed very wide. In passing we note that Maldonado did not record the entry by the right of the river Azul, either because it was not important enough, or because like today it entered the Madre de Dios at a place where this latter was divided into two, and the explorer has simply sailed on the other arm.

“Twenty leagues enters the river Guariguaca by the left, which is born in the province of yanagimes and boca negras” (The current rio de los Amigos) “eight leagues below by the right enters on the Magno the river Parabre which is born In the mountains of Carabaya “(Imambari nascenting in the cordillèra de Carabaya) “Twelve leagues enters the river Zamo by the right, by the back of the Toromonas, which is born in the territories of the Aravaonas” (Tambopata, this being confirmed by Brother Nicolás Armentia referring to the Franciscan writings of 1680 according to which the ” Religious order penetrated into the jungle at the level of Sandia at the sources of the Rio Tambopata, and arrived in Araonas territory.) “Thirty leagues below by the right enters the Omapalcas” (Heath, again the rio de las Piedras coming from the left was not seen because the Magno divides in two arms, one make a loop).

I doubt that Maldonado went further, I think he backed up and settled at the mouth of the Zamo, at the point now called “Puerto Maldonado”. Garcilazo mentions that the Indians welcome them at the beginning of their journey but change their attitude when they arrived at the Toromonas: Maldonado and two of his companions were captured. The Toromonas mentioned in La Relación reside well at the mouth of the river Zamo, and the Araonas or Aravaonas were upstream of this river, according to what is reported about them: on the right bank of the Madre de Dios and Forty leagues of the Cordillera of Peru is the province of the Aravaonas and more downstream is the province of the Toromonas … ” Maldonado heard of Paititi when it was retained by the Toromonas Indians and their cacique Tarano:

“There are immense plains fifteen leagues wide, to a high snowy ridge, which seems to be similar to that of Peru, according to the accounts of the Indians. The natives of the plains are called corocoros and those of the mountain called pamaynos. From this mountain they say that it is very rich in metals and is organized like a kingdom similar to that of Peru, with the same ceremonies (…) in the province of Paititi there are gold mines, silver and amber in large quantities. In the snowy cordillera there are many animals like those of Peru, but they are smaller. The natives are clothed in wool and also have crystal stones. ”

In fact, they well spoke to him of Peru … Plains of the Manu, the Cordillera of Pantiacolla, and behind, the snow-capped peaks of the Andes, unique on the continent. Mines he had missed. Of the Inca people who fled to Paititi with the “Ynga”. But Maldonado, in his exploratory euphoria and fantasies about the great emptiness that stretched before him à the east, did not for a moment contemplate that this city could be behind him.

Maldonado was liberated, but the other two, including his brother Simon, remained prisoners for two years. The conquistador returns to cusco to look for more men, but the month of november makes navigation difficult. Finaly, he survivors of the expedition emerged from the jungle south of Cusco near San Juan de oro, in the province of carabaya. At Cusco Maldonado was requisitioned to serve as camp chief during the campaign to subdue the so-called last capital of the resistance Vilcabamba, and during which he wrote this relationship in July 1572 to obtain permission to organize a second expedition. This will be refused to him by the viceroy, a decision of which there remains a letter in testimony, very unflattering to the conquistador judged to be incapable.

The name “Madre de Dios” would come from an exclamation that Maldonado would have uttered by seeing something that made him think of the holy virgin on a bank of the river. So it is after all perhaps she who, sickened by the atrocities committed in her name, saved Paititi.

The text of Maldonado, although somewhat forgotten for a time, definitely added to the confusion and mistakes of the Spaniards about Paititi. It is sometimes taken up by chroniclers who, by their interpretations, deform it a little more, leading to a further accentuation of the myth of a Paititi in the plains of Mojos, on the banks of the Mamoré, in the upper Guaporé, or completely lost in the heart of the continent of dense forest, at the end of the rio Madera …

Yellow : the main road on the cordillère of Paucartambo, and inca paths

Green : Rio Nistron & Rio Pini Pini

Blue : Rio Pantiacolla

Red : Rio Madre de Dios / Magno

Purple : Rio Manu / Paucarguambo

Fushia : Rio Colorado / Cuchoa

Orange : Rio de los Amigos / Guariguaca

Pink : Rio Imambari / Parabre

Turquoise : Rio Tambopata / Zamo

Dark blue : Rio Heath / Omacalpa

Other testimonies support the thesis of important access to Paititi by the Rio Manu :

Brother Juan de Odeja, in a letter of 1677 (taken up by Martua in 1906), reports that the Araonas and Toromonas had to pay a tribute to gold, silver, feathers and others to the Inca emperor. On their way to Cusco to do this, probably via the current province of Paucartambo, they saw a large Inca population who told them that the Ynga had been killed by the Spaniards, and that they fled to the Guarayos territory through a marshy plain in the backcountry, which in my opinion would be the basin of the present Manu. The Araonas reportedly said they saw in the lands of the Guarayos in question “Incas in a very large population, and in the middle the house of Apo, which they say is served with dishes of silver and gold and sitting on a bench in gold, and the walls inside the house of the idol are silver and gold that shines a lot. ”

The writings of Father Dominigo Alvarez de Toledo in 1661 (taken over by Brother Revello Bovo in 1848) tell us more about the location of these Guarayos at the time: the monk descended from the heights of Carabaya in the rainforest, changed its course and headed north, reaching the Toromonas, which occupied a large area between the Madidi and Madre de Dios rivers. He would have followed the same northerly direction, but we understand that he actually headed westwards, because he is heading a mission in the area of Paucartambo, and he says to us : “… Concerning the successor of the Inca who left Cusco of the Andes for the said town of Paititi, there is no doubt, because I joined the Nation of the Guarayos, who were those with whom he entered. ” This inevitably makes we think of the testimony of the Q’eros of Paucartambo.

In view of these testimonies, I therefore locate the lands of the Guarayos in the current province of Paucartambo. The area of Mameria, accessible by the Pini Pini, where the Apo (Apu) Catinti is the sacred summit, would be part of it, but apparently they can also reach their territory by making a detour through the interior, flat but marshy, the area of the Manu, which refers automatically to a people inhabiting Paititi. Which has also a sacred summit, as the drawing by Blas Valera shows.

Finally, how can we not mention among these testimonies that one the Jesuit father Andrés Lopez sends to Claude Acquaviva his superior in a letter discovered in 2001 by the researcher Mario Polia in the Vatican archives: At the beginning of the year 1576, four years after the death of Tupac Amaru, Father Andrés was appointed in the province of Willkapampa: Vilcabamba is the old one, since the Spaniards then knew its location, and therefore I presume that the province in question included at least the northern end of the cordillera de Paucartambo and the environs of Lacco, but also probably the lower jungle zone to the south of Pantiacolla, for according to Mario Polia, the priest reaches this area via “the Inca fort of Opatari” (Vargas Ugarte 1963) “in the land of the warrior Indians”, which clearly suggests the Antis / chuncos, or even to the fierce Guarayos evoked previously and located in this area. We have also seen that a road discovered by G. Deyermendjian ascended from the environs of Opatari on the Cordillera of Paucartambo, and led to Vilcabamba the old.

I think that was is on this occasion that, as the letter tells us, he converted a small Indian tribe who worshiped on his arrival a bezoar, a hard calculation forming in the belly of the cervidae, reputed to the four corners of the world for its medicinal properties. Having caused them to abandon this marvelous object for the Christian faith during the epidemic, Father Andres baptized them. Some of these new Christians, however, revolted by the exactions committed by the Spaniards, decided to flee to a kingdom “whose name is Paititi.” Father Andres offers one of them a crucifix, then a few months later he returns to Cusco where he has just been appointed Rector of the Jesuit Collège (November 1576), taking with him the Bezoar which he later gave to the Pope, delighted with this gift that he would sell a fortune …

Some time later in Cusco reappeared the three or four Indians who had fled. They then tell Father Andres an incredible story: When they arrived at the kingdom of Paititi, « whose king is very powerful, and governs with majesty a court similar to that of the great Turkish. His kingdom is very rich, adorned with gold, silver, and pearls in such quantities that they use them in kitchens for their pots and pans, as we use iron and other metals. » Having learned that they bore the representation of the god of the Christians, the curious king received them. When he saw the crucifix the sovereign laughed at them for a long time, and spat on it. It was then that, according to the Indians, a miracle occurred: the crucifix turned its head and cast tremendous looks around, causing the king and the whole court to prostrate for hours at the time. Convinced of the power of the god of the Christians, the king had a chapel built of gold and precious stones for the crucifix and adoration. He asked the Indians to put him in touch with someone who could teach him more about the Christian faith. This is how the Indians went to Cusco, where they meet Father Andrés.

It is then understandable that a meeting has happened, but it is not specified where. Cusco seems unlikely to me, so I think of Opatari. The King of Paititi was baptized by Father Andrés, but at that time “it pleased God to send him a fever that killed him.” Before he died, however, he promised the Jesuit priest to build a college and a church in massive gold, and ordered his only son and heir and the few nobles who accompanied them to introduce the Christian faith to Paititi. Father Andres reports all this to his Superior Father General during his trip to Rome in 1582, following which his Holiness the Pope decided to entrust to him the mission of evangelizing Paititi. But Father Andres lopez died on his return from Rome, at Hispanola (Cuba) in 1585. What happened to the mission? Marco Polia did not find any other information. However, a few years later, the secret Jesuit project to evangelize Paititi resurfaced, headed this time by Blas Valera, as we have seen.

From this incredible relationship we also draw some clues as to the location of Paititi: It would be situated « next to the Spanish province of Peru », which at the time stopped not far from Cusco in the Paucartambo range, and It is reached “within 10 days of walking”. This would correspond to the path through Opatari, where the Indians had to first look for Father Andrés, then climb the Pini-pini or the Rio Pantiacola, which is 200km in all, or 20km a day.

Confirmation by the elements on the ground

The concentration of sacred or utilitarian Inca and / or pre-Incas sites that we noted on the Andean side of Paititi is also found in the area of the other major access road to this city: the forest zone, and in particular, the southeastern end of the mountainous area of Pantiacolla.

We know that the Incas used this way of passage because Tupac Yupanki and his armies from Cusco established their base camp in Opatari (Pilcopata), which can be considered as the birthplace of the Madre De Dios. Going up from Pilcopata or Atalaya next to the river Piñipiñi and then its tributary the rio Nistron, we can run straight towards Paititi. If the rio does not reach it, we have access to the city by the valley to the east, little rugged.

This fluvial road between Paititi and Cusco seems to have been important. Unlike the parallel highway that we saw on the Paucartambo mountain range, everything indicates that the area around it was densely populated: the area of the sacred peak Apu Catinti in particular, was rich in discovery during the latter years. Among them, one of the most remarkable is the city of Mameria, unearthed in 1979 by Nicole and Herbert Cartagena, north of the peak. The sites of Choritia, Adumbaria, Chaku-Pangu, Niatene, Arete Perdido surround it and confirm the settlement. Currently, some Machiguengas are picking here coca leaves from seedlings that could be the wild descendants of those grown in ancient times. A path noticed by G. Deyermendjian seems to leave this area, and to go up the main track on the Paucartambo mountain range, passing through an inhospitable swamp and an abandoned tambo called San Martin.

It is also in the immediate vicinity to the north-east of this peak that Father Juan Carlos Polentini, based on the testimonies of the inhabitants of his parish and his own research, locates a rich gold mine discovered by Pachacutec during his journey in the province of Madre de Dios, and which would have been so productive that it would be largely responsible for the gold that covered the Kurikancha in Cusco. The exploitation would have occurred both in the open sky (gold being torn from the mountain by a waterfall) and digging the mountain. The ore would have been ferried by boat to the Nistron (maestron).

It is interesting to note that this thesis is accredited by another path discovered by Gregory Deyermenjian who notices that near the confluence of the Nistron and the Piñipiñi are important platforms, and that an other path connects this low zone and the main road. The path leads up to the summit of Llaqtapata where would have been an “Inca church”, some remains are visible, and by the Inca Tasquina site. It ascends the Rio Callanga along which there are circular vestiges, and climbs on Mount Callanga, where the researcher has noticed platforms “of an exceptional length”. Professor Salustio Gutierrez reports that the Inca fleeing the Spaniards would have used the word Kallankan to assure his people that sooner or later he would find the hidden city of Paititi (Gutierrez s / f and 1984). The path goes up finally in the forest by the western side of the Apu Pitama and joins the altiplano and the main way leading to Cusco.

Obviously, I do not think even just a moment that the assertion of Father Polentini, who likens this mine to Paititi, is the right one. According to him, it was at this point that the incas in flight would have surrendered, and there they would have hidden their sacred objects in gold. No, Paititi is farther to the north-east, as the so many solid proofs I give confirm. However, it is revealing that his local sources, to whom their ancestors had transmitted the idea for having worked, have told him about this site as Paititi.

Let us not forget that Paititi was a kingdom, and that it was above all known for its mineral wealth. The place being situated some sixty kilometers at most of the city, it is quite possible that it was part of its kingdom. This would probably place Mameria in his territory, or as an access.

Continue and end our tour of the access roads to Paititi, leaving from Opatari / Pilcopata to descend a little the Madre de Dios, then go up by its mouth the Rio Pantiacolla at our left. The latter is parallel to the Piñipiñi : like it, it rises high enough in the semi-mountainous and sylvestre massif, and likewise it takes its source not far from Paititi, to twenty kilometers at the most. Its path let me think that this was an important way of access to Paititi and communication of the latter with the plains of Mojos often mentioned as forming part of the “kingdom of the lord of Paititi”

Indeed, the Pantiacolla river has near its mouth a famous site, known as the “Paratoari pyramids”, which are actually only natural forms. However, it should be known that the Incas had a very special vision of the nature, the creations of the latter were intimately part of their space, and often they reworked them slightly to use or accentuate their sacred aspect. In the lagoons around these “pyramids” can be find hundreds of mysterious small pebbles carved in the form of hearts …

It is however from another well-known site, situated on a small tributary of this river, of which we will especially speak here:

The fabulous engraved cliff of Pusharo. Actually, when I wrote the previous paragraph, two days ago, I never really looked at Pusharo’s famous petroglyphs. The many researchers who have been interested in these engraved signs have very divergent opinions: creation of Inca, pre-Incas or Amazonian peoples, astronomical or rather mythological representations, shamanic visions, writing in primitive tocapus, or genuine plan for travelers going to Paititi … For my part I had only observed them quickly, and they had appeared totally incomprehensible to me.

However, in light of my discovery of Paititi nearby, the theory that the carved cliff of Pusharo would be a map leading to this city appeared to me more and more likely, given its strategic location mentioned above. I had resigned myself to simply accrediting this thesis by mentioning the other cases of this type of “indicator” petroglyphs in the region, as in Pangoa or in Ocobamba.

I also found very interesting the fact that still at the beginning of the 20th century anthropologists could note that the Matsigenkas populating the zone came to color some lines supposed to represent rivers and paths with the aid of vegetable pigments which they also used for their paintings Rituals. If rivers and paths were among these petroglyphs, the whole was therefore necessarily a map, or at least a map blank. Placed there near the mouth of the Pantiacolla, it could only lead to Paititi.

The French archaeologist Thierry Jamin supports this thesis. Having visited the site several times, he even claims to have deciphered the symbols, and to have found Paititi by following this map. The problem is that the place where he thinks this city is located is not the right one. True, it is close, about 10km from “my” mountain, but it is on a different massif. Given all the elements I have gathered, and the extreme precision of the drawings of Blas Valera which represent only my mountain, I do not doubt my results. Thierry Jamin would have therefore left a good track, but to be mistaken somewhere, I had at least to try to understand why.

Without much hope, I then began to read everything I could find on Pusharo, and to try to understand something to the hundreds of symbols of the immense wall. I was going to give up because of the immense complexity of the thing when I remembered to have often found myself in the course of my research in the same disarray, and that each time the solution was in fact quite simple. So I started again: If the wall was addressed to the travelers coming sometimes from very far in the forest as well as to the refugees of the Inca empire, it had to be easily comprehensible. Points of reference such as rivers and mountains must have been included.

I was lucky to find what is, and by far, the best drawing made on this site. Its author is none other than Thierry Jamin, who published it on his site Pusharo.com. I wondered a lot about whether or not I should present it here. This wall is more than important, I have the right to study it as another, and I have deciphered it by my own means..

I would, however, have gladly refrained from disclosing my results here to leave him this honor. What drives me to use his work is that he made a mistake at the end of his reasoning, and therefore his result is wrong. If I publish my conclusions without treating this point, he will be the first to argue that I am wrong on the basis of those same drawing of the wall. In order to leave no doubt as to the accuracy of my discovery, and at the same time justify my questioning of his conclusions which may seem insolent, but which is only realistic, I will quote here a small part of his scientific work he published, in the form of this drawing.

However, I would like to bow to this researcher who was the first to understand the importance of this wall, and who is probably the best specialist of Paititi in the world. His expertise and his dedication to the cause of this city make him an indispensable asset for the future study of the site.

Thanks to his drawing, for the first time I could understand the true dimension of the site, and its true layout (over tens of meters) :

I have the advantage of knowing where Pusharo and Paititi are. In the perspective of a map, the concentration of important symbols on the right makes me think that it is Paititi. The wall being at Pusharo, it seemed to me probable that this point of departure is therefore situated on the left. And very quickly indeed, two symbols caught my attention:

These are the two geoglyphs still observed by the same Thierry Jamin near the site of Pusharo, which locates this site on the map obviously for all travelers, whatever their language.

It is by observing that the right turn ending in the “cul de sac” present near these symbols corresponded perfectly to the river actually passing at the foot of the wall of Pusharo on Google Earth that I understood one thing paramount : the lines Which enamel the wall are not, as I thought until then, the faults of the rock, but they represent the rivers and / or roads, the famous geographical landmarks I was looking for. Could it be that simple? I forgot the dozens of symbols, and repassed these lines in red. I was amazed at the correspondence I could see:

Absolutely ALL is there. And with remarkable precision. It is so precise that I will dispense with comments on the course of the main rivers (red) which are obviously also paths, for otherwise they are represented by a spiral followed by small waves (blue). A large rocky bar, which forms an important cliff along its entire length, is indicated by a big plot (purple)

The small red “Y” corresponds in fact to the meeting point of three roads : one coming from the end of the Cordillera de Paucartambo where we saw Vilcabamba was, one coming from the “gate” of the Amazon as I called it at the beginning of my researches, and therefore at Paititi, the last branch points down, towards what suddenly resembles seeing the wall of Pusharo, as the suburb of a city still more immense than what I thought. Look at the distances … The bulk of the site, which begins two-thirds of the cliff, is in all 50km long …

With a closer look, in fact even the small roads that allow traffic in the neighborhoods are detailed. Having become quite good to find the old roads and fields or traces of buildings on Google Earth despite the vegetation, (in fact the old version of this software 7.0.2.8415 is better to find it, because of an ancient sattelite view in low quality) this fabulous map enabled me to identify hundreds of them on the ground, in just a few hours , which suggests that there are many others.

All the paths that I have found are still thought of in a very logical way: they generally follow the curves of the terrain so as not to have to go up and down, because the relief, which does not seem enormous from this satellite point of view , Is actually rather undulating. Some paths, however, inevitably climb, zigzagging.

Looking for the paths, I realized that many of the engraved elements were not theoretical symbols, but a description of the reality on the ground: thus the many small staircases are nothing but the ascending paths, which ascend in a zigzag pattern. The many spirals must also have a meaning of the same type that I still have difficulty identifying but which I think I discover by spending a little more time studying the terrain.

The big “X” also corresponds to a reality on the ground: on a large cliff, two enormous faults form an “X” quite identical, very visible from the paths, and therefore an excellent landmark.

Having found a concentration of large platforms at the top of the neighboring mountain of Paititi, very high and imposing, I think that the oval divided into small diamonds with points indicates a very important fortress given the strategically strategic location, hardly accessible. The diamonds and points would give indications on the garrison. But this is only a hypothesis.

Other symbols seem to represent units of account, demographic perhaps, but I think also agricultural. Indeed on the drawing of Blas Valera, on this side opposite to the dam, we can discern a corn plant, and this aspect is found in what Diego Alemán heard about Paititi. The structures that I have found since the beginning, for the most part, seem by in their dimensions to correspond more to walls surrounding fields or flocks than to buildings. However, I found in a book by Fernando Santos Granero the trace of a relationship of Martín Hurtado de Arbieto who, starting from Huánuco in the north enters the forest and discovers an astonishing building … 525 meters wide, with 20 doors, where Matsisgenkas resided.

Finally, it seems almost certain that the rest of the symbols represent either buildings or human groups (clans, ethnic groups, chiefdoms) given their distribution in what resembles residential neighborhoods served by roads.

As with the Jesuit card representing the Madre de Dios, by observing the incredible correspondence of the engravings with the view of the sky, we can wonder how did the incas did it… In fact, here this is explainable : most of the roads and buildings are built on a more or less abrupt rock face. The same goes for rivers, which are actually torrents. So that seen from below, we had to have a vision close enough to what is represented. Maybe it was the same for the basin of the Madre de Dios, seen from the top of the Cordillera of Paucartambo.

It would be offensive to the cartographic genius of the inhabitants of Paititi to summarize their art to this, for there is nevertheless a real will to conceptualize the terrain and elevate the point of view, especially to the left of the map, but you must understand that this idea is extremely important for the future.

Let us now turn to what interests us at first: I have voluntarily set aside the representation of Paititi, here it is :

It is only by knowing Paititi that we can really understand this drawing. Indeed, if we continues to read the map as before, seen from the sky, the earth surrounded by water (the mountain with the five peaks) seems to be only slightly densely populated, the essential symbols appearing to be located beyond at the right. This is exactly what Thierry Jamin had to think.

Knowing Paititi perfectly, and the location of the sacred enclosures drawn by Blas Valera, necessarily synonymous with the heart of the city, I had a different point of view. For the sake of realism, I think that the first engravers of Pusharo represented this loop formed by the river on the scale and in the same style as the rest of the fresco, seen from the sky. But that was a problem. I remembered being a child, drawing a bubble with a pen to make a character speak, and then realizing that I had absolutely no place to write everything I wanted to make him say. This is exactly what happened: the very important symbols that had to appear on the site of Paititi overflowed. It is thus that we finds the profile face of the Grand Ancestor (yaya, gran candire, white king, etc …) or the Inca according to the paternity of the fresco, outside the loop representing the river, thus appearing to be situated on the mountain next door. On the one where Thierry Jamin hopes to find Paititi.

We can understand everithing while remembering that the more the map advances, the more the engravers have represented slopes of populated mountains seen from below, and not from an aerial view. This evolution reaches its climax at the end of the fresco at Paititi: Indeed, an important line, which has nothing to do with reality on the ground, contrary to all others, represents the crest of the mountain with five summits from below. In order to make the traveler understand that it is actually the center of the loop formed by the river, its trail begins in the loop, but it exceeds.

Above all, we can see that on the right is the valley which separates our mountain with five summits from the neighboring mountain: the steep promontory formed by the latter is clearly identifiable. Thierry Jamin, although the authorization he has been waiting for years is finally granted, will not find Paititi on this promontory, which has no symbol.

Here. We can even see one of these spirals joined to a series of small waves (lower right) but much more accentuated than the rivers mentioned above, and which is exactly at the right location to represent the reservoir of artificial water we considered . A strange little “x” crosses it, which lets me think that it tells the travelers the beginning of the “path paved with black stones” which constitutes the main access to the upper city, from this lagoon precisely. I tried to find a fairly close view on Google Earth, but it’s complicated:

Interestingly, the geoglyphs that appear to be everywhere on the Pusharo wall do not include any of the 12 large specimens surrounding Paititi from Blas Valera’s drawing, which makes me think that the Pusharo fresco must be prior to their realization. Concerning the other mysterious symbols that dot this face of my plateau … And this cross at the top of the wall, I confess that I do not understand anything yet, but with a little time who knows …

An overview of my discovery:

I think it would be very interesting to dig at the foot of the Pusharo wall. Indeed, the river that borders it, following its many floods, has buried the bottom of this wall under several meters of silt, as evidenced by the reports of the first observers of the site. Perhaps other occupied sites, located to the north on the upper basin of the Manu, were indicated.

Conclusion

We can conclude from paths and evidences presented that the testimonies and rumors that are transmitted from generation to generation in the provinces north of Cusco are based.

After centuries of fruitless research, academic negations, mockery of those who believed in the last refuge of the Incas who had survived there for a certain period, I think I can affirm that I have discovered the mythical city of Paititi.

My work proves in a certain way the existence of this city, by various reasonings valid independently of each other, and all based on data from the field or documents of time. I thus discovered the precise location of Paititi, and more, gives a relatively complete plan of Paititi. By publishing this information Me, Vincent Pélissier, hope to advance the science, and thinks I am worthy, by the precision and seriousness of my work, to be recognized as the inventor of this site.

The decision to publish the result of my work was not taken with gaiety of heart, I even did everything to avoid this. I am aware that it will have important consequences. The attached document is intended to explain what circumstances forced me to publish my discovery.

Vincent Pélissier 2016

PS: Thank you for excusing the spelling mistakes and grammar errors in English

© Vincent Pélissier 2016