The Legend of Paititi

Paititi is one of the very few great mythical cities. Its legend has traveled the globe, as well as that of Atlantis, the lost continent of Mu, or the mines of King Solomon. Indeed, Paititi is not any lost city: after the conquest of the Inca empire by the Spaniards, this unattainable city has become, in the mind of all, the Eldorado. It makes dreamed millions of people throughout history, which has unfortunately cost tens of thousands of lives, without being discovered to this day. The very mystical Paititi is surrounded by a true legend, the main features of which are as follows:

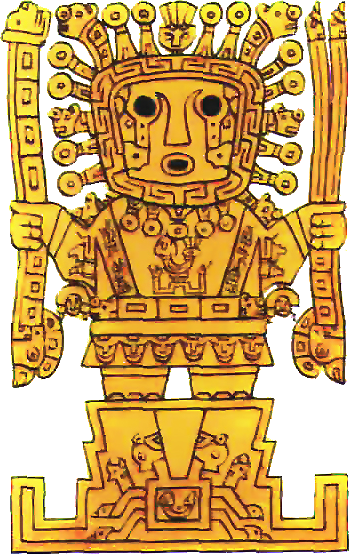

One does not become the Eldorado without concealing a fabulous treasure: Paititi would be the secret city where the last Inca, having noticed the limitless appetite of the invaders for gold, would have sheltered the vast majority of their sacred objects. When this precaution was taken, the Spaniards were still only a handful, but had already plundered tons of gold and silver. When they tortured prisoners to find out where the rest had gone, they would have taken a single grain in a pile of corn, saying, “Here is the part of the treasure that you have managed to take. The rest has been sheltered, and will escape to you forever ”

Paititi is the European name for Paikinkin or Paiquinquin Qosqo which means “the twin of Cusco”. Knowing the size, the architectural splendor, the incredible luxury of the Inca capital, the navel of one of the greatest empires of all times to which all wealth, all know-how converged, we understand that its ” Twin “can not be a small classic city. Paititi would be an immense city, the most impressive archaeological discovery of the century. Especially because, unlike the great Angkor or the majestic Egyptian vestiges, it would never have been looted.

According to the legend, Paititi is the mystical city of knowledge. The center and origin of Inca beliefs, the greatest sacred place of this civilization. The place where a mysterious Andean writing would have been confined, coming from older Amazonian civilizations, and jealously guarded by the Inca sages. They would have thus recorded all the history, the knowledge, the rites of their people. But also all the secrets of the mysterious civilizations that preceded them on the sierra and of which they conquered the former territory (Nazca, Tiahuanaco ..). Paititi would be a true library on the past of a continent that is still quite unknown today because of the lack of a written record.

Finally, the kingdom of Paititi, located somewhere in the inaccessible and still very unknown Amazon forest, would have been the refuge and capital of the last Inca emperors. They would have restored here their court after the capture of Cusco by the Spaniards, and would, thanks to the secret always maintained around this sacred city, had remained at a distance from any intrusion. Since then, the elders of the Andes say that “In Paititi lives Inkarri Intipchurrin (the Inca King Sovereign Son of the Sun) who until now reigns in silence, preparing to re-establish the interrupted order of the universe. ”

Paititi, this legendary city … I discovered it.

And this is not a joke, or the delirium of a crank.

I am the first to be surprised, but the proofs are there and solid, as you will be able to judge by yourself.

How Paititi became the Eldorado

At the beginning of the legend of Eldorado, there would be a narrative:

The Spaniards firmly set foot on the Peruvian coast in 1532. As they explore the region, an Indian carrying a message to the Inca Atahualpa falls into their hands. When questioned, he finally revealed that he was originally from the north of the empire, and he confided to them that a tribe east of his own carried out a ritual that interested the Spaniards in the highest degree: The monarch was anointed with essence of Turpentine, and then entirely covered with gold glitter, in order to shine like the sun. He embarked on a raft covered with gold offerings, and immersed himself in the lake to purify himself while the nobles who accompanied him threw the treasures into the sacred lake.

Captain Sebastian de Benalcazar baptized this sovereign “El Dorado”, that is to say “the Golden”. In fact, the Muiscas in Colombia had a similar ritual for centuries before, but the Spaniards knew nothing of it. Influenced by the myth already known of the “Golden Cities” to the Indies (in fact the golden roofs of the asian pagodas seen by the first Europeans), the Eldorado quickly became for them a place rather than a person, because they thought that this Monarch had to live in a city extremely rich in treasures to allow himself to throw such quantities of it into the water each year.

Arriving in the middle of the civil war in the empire, the Spaniards played their part very well, and succeeded in making many allies among the peoples who had been subjected for too long to the Incas, who had been left free from their movements since the latter had torn apart. At the end of a particularly adventurous episode, Pizarro succeeded in capturing the one closest to stabilizing the empire, the Inca Atahualpa. After having received an enormous ransom for his liberation, he had him executed. Subsequently Manco Inca will help the conquistador to conquer Cusco, which the troops of Atahualpa still held.

Manco Inca was to govern, but he quickly deceived: the Spaniards, supported by their local allies, humiliated him and reduced him to the role of puppet. The Inca then revolted and united an immense army, besieging Cusco and Lima, where the Spaniards and their allies had taken refuge. However in 1536 his troops were defeated in the north and he can no longer hold the siege of the city. He would have gathered together through the immense empire all the sacred objects of precious metal that the conquistadors had not yet stolen, and sank with this treasure into an inaccessible region that had remained untouched by Spanish presence.

When Cusco is resumed, some of Manco’s supporters are taken prisoner. Pressed by the questions of the Spaniards, the prisoners then gathered an important pile of corn, and then gave a single grain to their executioners: it was, they thought, the portion of the Inca treasure that the Spaniards were able to steal. The rest, including a two hundred meter gold chain whose links were the size of an inch, would escape them forever. Leaving Cusco, the Inca passed through Lares, in the northeast, known for being the holiday home of many nobles, probably amassing a lot of valuable goods. It is also known that he recovered the sacred mummies of his ancestors from Cusco, probably by going to empty the sanctuaries where they were covered with precious offerings.

Where is this treasure? Chroniclers mention a column of 20,000 lamas laden with gold, which then crossed the mountains at the level of a certain Vilcabamba. Finally, a rumor spread in the capital, and was sustained enough to endure to the present day: The Inca would have taken refuge in a secret city where he would have put the sacred treasures in safety and restored his court, in order to persist Empire and one day return to power. This city was called Paititi, but no inhabitant could clearly say where it was located. The very mystical and highly sacred “sister of Cusco” probably owed her survival to the fact that the rare scholars, priests and nobles who knew her location had fled to join her with Prince Inca Shock Auqui during the Civil War a few years earlier , or with Manco Inca.

The chronicler Maúrtua reports that eventually one of the inhabitants questioned would have ended up saying that “The Inca, the crowns and many other things are at the junction of the river Païtiti and the river Pamara, three days Walk from the Manu River “. But the Spaniards could not immediately go after him, for the war between them for the control of Cusco caused them to lose almost a year. When a detachment of cavalry found Manco Inca in June 1537, he was in Ollantaytambo with a small troop and fell back on Chuquichaca, then Vitcos. But no one knows what he did for a year, and with him no more cumbersome treasure.

Never had the treasure been found by the Spaniards, for good reason : They did not know where the empire territory stood, nor in what direction to look for Paititi, or any other city that might have resembled the Eldorado. The region is gigantic, particularly inhospitable for Europeans, and the word is still weak. The difficult, narrow and tortuous paths are as many possible ambush sites from a guerrilla perspective, which Manco in the mountains, or the Indian tribes in the forest, were able to exploit to return their few expeditions to their homes, decimated.

It is interesting to read Antonio de Herrera’s account of the expedition led by Pedro de Candía from June to October 1538. This soldier and faithful friend of Pizarro obtained information from a native concubine , who described to him an extremely rich land called Ambaya, situated to the east of the Andes. Pedro de Candía invests all his personal part of the loot (85,000 pesos of gold, or nearly 400 kg all the same, which gives a glimpse of what the Spaniards plundered already in 1538 …) in the expedition. It was a calvary and a bitter failure.

Many others attempted the adventure and set out in search of the lost golden city, in the 16th century but also later, and up to the present day. If they all failed, Paititi’s unrestrained quest led to the conquest of a large majority of the South American continent.

Here are the most interesting expeditions:

In 1539 Sebastian de Benalcazar learned that the tribe of the Muiscas, neighboring the Inca empire to the northeast, had the habit of immersing his sovereign in a sacred lake. The local Indians brought him to the sacred lake of Guatavita, nestled in the crater of a volcano about 50 km north of present-day Bogota. No golden city, no riches in this tribe on the decline which was far from competing in techniques and prosperity with the Inca empire. Only a lake at the bottom of which rests possible offerings, inaccessible. The myth of the Eldorado, which had probably took its origine here, persisted.

In 1541 Gonzalo Pizarro and Francisco de Orellana also went in search of the famous Eldorado, this time by identifying it as Paititi, the city of lost treasure, the “Land of Cinnamon” as the Incas described him (because to them gold had no market value, in contrast to the spices and medicinal plants). They left the Zumaco valley, arrived in the Coca River valley in June and took as a guide the chief of the tribe Omagua. From the strong force of 300 Spaniards and 4,000 Indians they taken, a great majority died of hunger, fever, or in the arrows of warlike Indians. Orellana burned and eaten by his dogs his native guides who had not led him to the Eldorado. He then built a skiff to fetch food on the Rio Napo, but carried away by currents he made an incredible 4800 km travel to the mouth of the river. Along the way he will relate having fought a tribe headed by white women warriors, and baptize the river “Amazon”.

Spanish have tortured at that time countless unfortunate Indian for information about Eldorado. In 1550 an expedition led by Francisco de Aquino leaves Cuzco in search of the kingdom of Paititi, but failed. In 1588, another attempt by Juan Alvarez Maldonado knew a tragic end. When in 1572 the last Inca is captured with few troops in a place the Spaniards believed for decades to be its capital, they come across a small village, ash, which had nothing to do with a city of gold, or rather a real city. The troops will soon abandon this difficult woody and mountainous region, without any economic or strategic interest.

Following the successive failures terribly costly in human lives, in the seventeenth century the kingdom of Paititi is somewhat forgotten. Only the Jesuits implanted in the confines of the Madre de Dios region stayed interested in Paititi, and gathered informations confirming the existence of this city: For example the letter that Father Andrea Lopez address to his superior Claude Acquaviva, discovered in 2001 by archaeologist Mario Polia in the Vatican archives, where he describes a kingdom of Paititi inordinately rich in gold and silver, retaining the Inca metallurgy and monumental construction techniques, and an advanced political organization headed by an Inca.

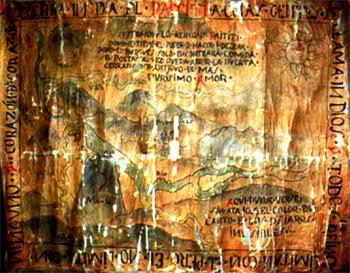

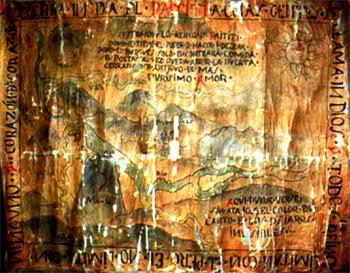

Also, a very interesting description of Paititi was made by Francisco de Cale in 1686 according to the testimony of a native, and another by Benito Jerónimo Feijoo in 1730… An old map translated at this time of Quechua by a Jesuit missionary is preserved today in the ecclesiastical museum of Cuzco. On the bottom of the card are drawn rivers and mountains, and above it a mysterious text that seems esoteric. Found much time later, it will sharpen the curiosity of modern adventurers.

In the middle of the eighteenth century Paititi resurfaced, especially in Cuzco, but took on mythic dimensions. Thus, during the rebellion of May 1742, the Peruvian Juan Santos Atahualpa knew that “a cousin brother reigned in the Great Paititi” as reported by Dr. Franklin García Irigoyen. Was it a way to revolt the horribly oppressed people, citing the figure of the Inca?

At the same time, in the other side of the continent, an anonymous Portuguese adventurer drew upon the story of Roberio Dias, little son of one of his compatriots who lived among the Indians, to embark in search of gold and diamonds mines in the depths of the Brazilian rainforest. His endless travel took him the much further he anticipated, until that he has described as an area around a mountain range, south-east / north-west. He discovered a huge city with cyclopean walls, so typical of Inca’s architecture, half covered with vegetation. It seems that he was close to the spanish Peru because he wrote in his manuscript he dreaded to meet an armed troop of that rival nation.

In the nineteenth century Paititi, the third great kingdom of Americas which capital is a city full of hidden treasures for centuries lost deep in the Amazon, is definitely assimilated to the mith of Eldorado, and the one of the golden cities. And by the same movement relegated as a legend by Alexander Humbolt, who was mapped the continent.

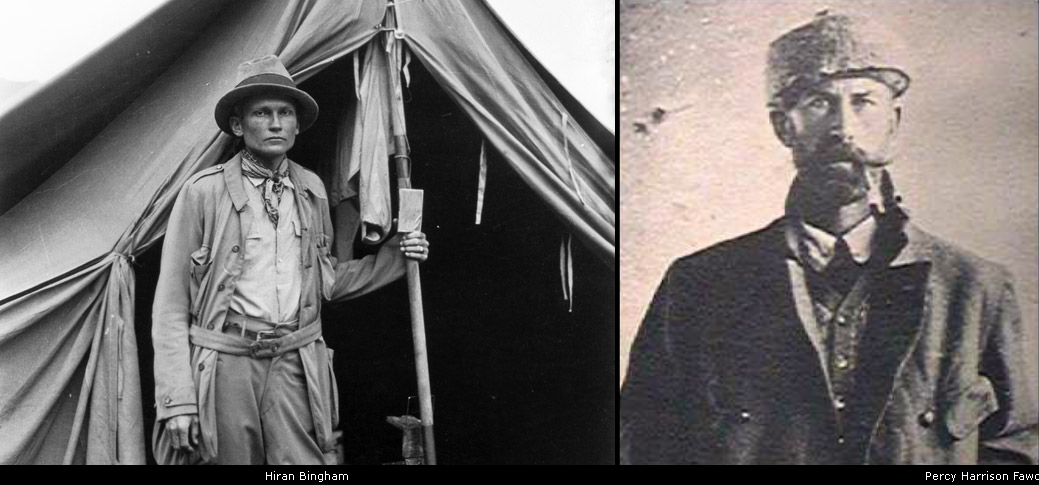

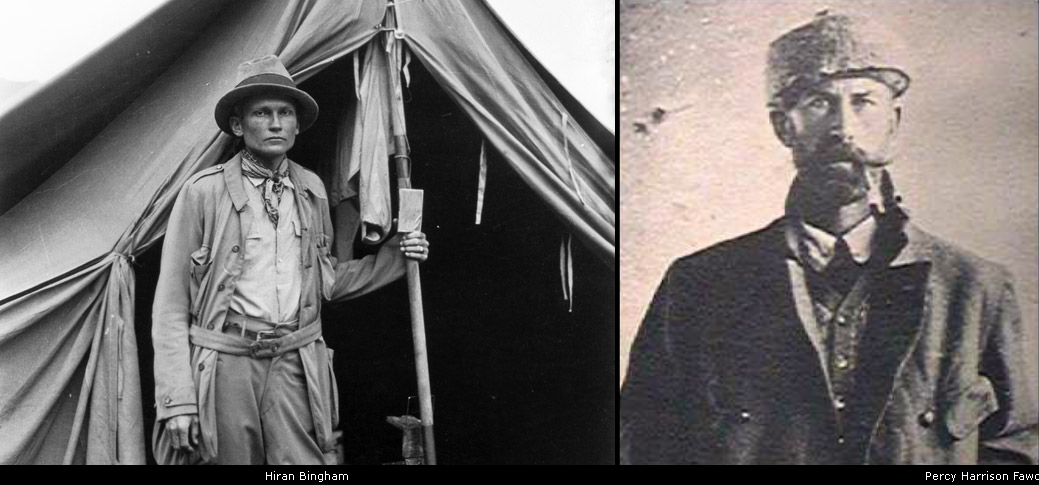

This did not prevent Hiran Bingham to found Machu Picchu in 1912, while searching Paititi.

In the 1920s, Sir Percy Harrison Fawcett, a quite eccentric but courageous English officer drew upon the Portuguese manuscript (whose adventure is recounted above) to search for traces of the descendants of the Atlanteans, whose, according to jim, took refuge deep in the Amazon, and were at the origins of pre-Inca cultures. Accumulating evidences from native’s stories and explorations during his eight expeditions, he thought he had discovered the outpost of a great city in the Mato Grosso region, at the foot of a mountain. He disappeared into the jungle on the eve of his advertised discovery.

Fawcett knew a certain mediatization, and gave birth to vocations. Since the 1960s dozens of archaeological expeditions, which sometimes ended tragically, were conducted to find the lost city of Paititi. I will not enumerate them here, but draw two conclusions :

All together, they explored only one hundredth of this continent of dense forest.

And throughout the huge forest area that corresponded to the Antisuyu, remains and even small Inca cities were found. This region, still poorly known, one of the four great provinces of the empire, must have had a capital …

A “legend” that sounds too real

If, as we have seen, it has been assimilated little by little to the Eldorado or the Golden Cities, which are myths or the imaginary distortion of real facts, after 400 years Paititi continues to sharpen, maybe more than ever, the curiosity of archaeologists. Some of the most recognized of them even begin to have the courage to at least consider its possible reality: Indeed many recent discoveries question the dogma imposed by the academy which, in the right line of the Spanish colonialist mentality, refuses since the XVIth century to conceive that in the forest of the “savages” could had been developed any form of civilization.

If the lost kingdom of Paititi in particular arouses so much interest from the professionals, it is because its “legend” has a peculiarity: Its sources are very numerous, and some very reliable, because they are the same ones that allowed us to know the Inca history. Above all, all these sources, however distinct in time and space, converge on the smallest details.

The elements that compose the “legend” of Paititi come from two groups of sources:

These are mostly narratives of chroniclers of the time, who report the testimonies of local Indians or Incas interrogated about Paititi, its location, or what was there. While some authors tended to distort the facts, it was not systematic far from it, and others are deemed much more reliable. The multiplicity and the concordance of the narratives of the time necessarily involves.

Other sources are more recent: they are memories transmitted orally and collected by modern anthropologists from tribes that remained isolated until very recently as the Q’eros, or by the religious from the populations of the valleys north of Cusco, where these stories are told during the vigils for generations, in each family.

Another aspect that appeals is that this “legend” contains not at all fantastic element or chimerical creature. On the contrary, all the descriptions indicate characteristics of the geography of the terrain, of certain buildings, names of places, distances, and even precisely describe a certain way of life, habits, know-how, a particular social organization, etc.

These many realistic details and the multiplicity of sources suggest that everything could not be invented.

PS: Thank you for excusing the spelling mistakes and grammar errors in English

© Vincent Pélissier 2016

The Legend of Paititi

Paititi is one of the very few great mythical cities. Its legend has traveled the globe, as well as that of Atlantis, the lost continent of Mu, or the mines of King Solomon. Indeed, Paititi is not any lost city: after the conquest of the Inca empire by the Spaniards, this unattainable city has become, in the mind of all, the Eldorado. It makes dreamed millions of people throughout history, which has unfortunately cost tens of thousands of lives, without being discovered to this day. The very mystical Paititi is surrounded by a true legend, the main features of which are as follows:

One does not become the Eldorado without concealing a fabulous treasure: Paititi would be the secret city where the last Inca, having noticed the limitless appetite of the invaders for gold, would have sheltered the vast majority of their sacred objects. When this precaution was taken, the Spaniards were still only a handful, but had already plundered tons of gold and silver. When they tortured prisoners to find out where the rest had gone, they would have taken a single grain in a pile of corn, saying, “Here is the part of the treasure that you have managed to take. The rest has been sheltered, and will escape to you forever ”

Paititi is the European name for Paikinkin or Paiquinquin Qosqo which means “the twin of Cusco”. Knowing the size, the architectural splendor, the incredible luxury of the Inca capital, the navel of one of the greatest empires of all times to which all wealth, all know-how converged, we understand that its ” Twin “can not be a small classic city. Paititi would be an immense city, the most impressive archaeological discovery of the century. Especially because, unlike the great Angkor or the majestic Egyptian vestiges, it would never have been looted.

According to the legend, Paititi is the mystical city of knowledge. The center and origin of Inca beliefs, the greatest sacred place of this civilization. The place where a mysterious Andean writing would have been confined, coming from older Amazonian civilizations, and jealously guarded by the Inca sages. They would have thus recorded all the history, the knowledge, the rites of their people. But also all the secrets of the mysterious civilizations that preceded them on the sierra and of which they conquered the former territory (Nazca, Tiahuanaco ..). Paititi would be a true library on the past of a continent that is still quite unknown today because of the lack of a written record.

Finally, the kingdom of Paititi, located somewhere in the inaccessible and still very unknown Amazon forest, would have been the refuge and capital of the last Inca emperors. They would have restored here their court after the capture of Cusco by the Spaniards, and would, thanks to the secret always maintained around this sacred city, had remained at a distance from any intrusion. Since then, the elders of the Andes say that “In Paititi lives Inkarri Intipchurrin (the Inca King Sovereign Son of the Sun) who until now reigns in silence, preparing to re-establish the interrupted order of the universe. ”

Paititi, this legendary city … I discovered it.

And this is not a joke, or the delirium of a crank.

I am the first to be surprised, but the proofs are there and solid, as you will be able to judge by yourself.

How Paititi became the Eldorado

At the beginning of the legend of Eldorado, there would be a narrative:

The Spaniards firmly set foot on the Peruvian coast in 1532. As they explore the region, an Indian carrying a message to the Inca Atahualpa falls into their hands. When questioned, he finally revealed that he was originally from the north of the empire, and he confided to them that a tribe east of his own carried out a ritual that interested the Spaniards in the highest degree: The monarch was anointed with essence of Turpentine, and then entirely covered with gold glitter, in order to shine like the sun. He embarked on a raft covered with gold offerings, and immersed himself in the lake to purify himself while the nobles who accompanied him threw the treasures into the sacred lake.

Captain Sebastian de Benalcazar baptized this sovereign “El Dorado”, that is to say “the Golden”. In fact, the Muiscas in Colombia had a similar ritual for centuries before, but the Spaniards knew nothing of it. Influenced by the myth already known of the “Golden Cities” to the Indies (in fact the golden roofs of the asian pagodas seen by the first Europeans), the Eldorado quickly became for them a place rather than a person, because they thought that this Monarch had to live in a city extremely rich in treasures to allow himself to throw such quantities of it into the water each year.

Arriving in the middle of the civil war in the empire, the Spaniards played their part very well, and succeeded in making many allies among the peoples who had been subjected for too long to the Incas, who had been left free from their movements since the latter had torn apart. At the end of a particularly adventurous episode, Pizarro succeeded in capturing the one closest to stabilizing the empire, the Inca Atahualpa. After having received an enormous ransom for his liberation, he had him executed. Subsequently Manco Inca will help the conquistador to conquer Cusco, which the troops of Atahualpa still held.

Manco Inca was to govern, but he quickly deceived: the Spaniards, supported by their local allies, humiliated him and reduced him to the role of puppet. The Inca then revolted and united an immense army, besieging Cusco and Lima, where the Spaniards and their allies had taken refuge. However in 1536 his troops were defeated in the north and he can no longer hold the siege of the city. He would have gathered together through the immense empire all the sacred objects of precious metal that the conquistadors had not yet stolen, and sank with this treasure into an inaccessible region that had remained untouched by Spanish presence.

When Cusco is resumed, some of Manco’s supporters are taken prisoner. Pressed by the questions of the Spaniards, the prisoners then gathered an important pile of corn, and then gave a single grain to their executioners: it was, they thought, the portion of the Inca treasure that the Spaniards were able to steal. The rest, including a two hundred meter gold chain whose links were the size of an inch, would escape them forever. Leaving Cusco, the Inca passed through Lares, in the northeast, known for being the holiday home of many nobles, probably amassing a lot of valuable goods. It is also known that he recovered the sacred mummies of his ancestors from Cusco, probably by going to empty the sanctuaries where they were covered with precious offerings.

Where is this treasure? Chroniclers mention a column of 20,000 lamas laden with gold, which then crossed the mountains at the level of a certain Vilcabamba. Finally, a rumor spread in the capital, and was sustained enough to endure to the present day: The Inca would have taken refuge in a secret city where he would have put the sacred treasures in safety and restored his court, in order to persist Empire and one day return to power. This city was called Paititi, but no inhabitant could clearly say where it was located. The very mystical and highly sacred “sister of Cusco” probably owed her survival to the fact that the rare scholars, priests and nobles who knew her location had fled to join her with Prince Inca Shock Auqui during the Civil War a few years earlier , or with Manco Inca.

The chronicler Maúrtua reports that eventually one of the inhabitants questioned would have ended up saying that “The Inca, the crowns and many other things are at the junction of the river Païtiti and the river Pamara, three days Walk from the Manu River “. But the Spaniards could not immediately go after him, for the war between them for the control of Cusco caused them to lose almost a year. When a detachment of cavalry found Manco Inca in June 1537, he was in Ollantaytambo with a small troop and fell back on Chuquichaca, then Vitcos. But no one knows what he did for a year, and with him no more cumbersome treasure.

Never had the treasure been found by the Spaniards, for good reason : They did not know where the empire territory stood, nor in what direction to look for Paititi, or any other city that might have resembled the Eldorado. The region is gigantic, particularly inhospitable for Europeans, and the word is still weak. The difficult, narrow and tortuous paths are as many possible ambush sites from a guerrilla perspective, which Manco in the mountains, or the Indian tribes in the forest, were able to exploit to return their few expeditions to their homes, decimated.

It is interesting to read Antonio de Herrera’s account of the expedition led by Pedro de Candía from June to October 1538. This soldier and faithful friend of Pizarro obtained information from a native concubine , who described to him an extremely rich land called Ambaya, situated to the east of the Andes. Pedro de Candía invests all his personal part of the loot (85,000 pesos of gold, or nearly 400 kg all the same, which gives a glimpse of what the Spaniards plundered already in 1538 …) in the expedition. It was a calvary and a bitter failure.

Many others attempted the adventure and set out in search of the lost golden city, in the 16th century but also later, and up to the present day. If they all failed, Paititi’s unrestrained quest led to the conquest of a large majority of the South American continent.

Here are the most interesting expeditions:

In 1539 Sebastian de Benalcazar learned that the tribe of the Muiscas, neighboring the Inca empire to the northeast, had the habit of immersing his sovereign in a sacred lake. The local Indians brought him to the sacred lake of Guatavita, nestled in the crater of a volcano about 50 km north of present-day Bogota. No golden city, no riches in this tribe on the decline which was far from competing in techniques and prosperity with the Inca empire. Only a lake at the bottom of which rests possible offerings, inaccessible. The myth of the Eldorado, which had probably took its origine here, persisted.

In 1541 Gonzalo Pizarro and Francisco de Orellana also went in search of the famous Eldorado, this time by identifying it as Paititi, the city of lost treasure, the “Land of Cinnamon” as the Incas described him (because to them gold had no market value, in contrast to the spices and medicinal plants). They left the Zumaco valley, arrived in the Coca River valley in June and took as a guide the chief of the tribe Omagua. From the strong force of 300 Spaniards and 4,000 Indians they taken, a great majority died of hunger, fever, or in the arrows of warlike Indians. Orellana burned and eaten by his dogs his native guides who had not led him to the Eldorado. He then built a skiff to fetch food on the Rio Napo, but carried away by currents he made an incredible 4800 km travel to the mouth of the river. Along the way he will relate having fought a tribe headed by white women warriors, and baptize the river “Amazon”.

Spanish have tortured at that time countless unfortunate Indian for information about Eldorado. In 1550 an expedition led by Francisco de Aquino leaves Cuzco in search of the kingdom of Paititi, but failed. In 1588, another attempt by Juan Alvarez Maldonado knew a tragic end. When in 1572 the last Inca is captured with few troops in a place the Spaniards believed for decades to be its capital, they come across a small village, ash, which had nothing to do with a city of gold, or rather a real city. The troops will soon abandon this difficult woody and mountainous region, without any economic or strategic interest.

Following the successive failures terribly costly in human lives, in the seventeenth century the kingdom of Paititi is somewhat forgotten. Only the Jesuits implanted in the confines of the Madre de Dios region stayed interested in Paititi, and gathered informations confirming the existence of this city: For example the letter that Father Andrea Lopez address to his superior Claude Acquaviva, discovered in 2001 by archaeologist Mario Polia in the Vatican archives, where he describes a kingdom of Paititi inordinately rich in gold and silver, retaining the Inca metallurgy and monumental construction techniques, and an advanced political organization headed by an Inca.

Also, a very interesting description of Paititi was made by Francisco de Cale in 1686 according to the testimony of a native, and another by Benito Jerónimo Feijoo in 1730… An old map translated at this time of Quechua by a Jesuit missionary is preserved today in the ecclesiastical museum of Cuzco. On the bottom of the card are drawn rivers and mountains, and above it a mysterious text that seems esoteric. Found much time later, it will sharpen the curiosity of modern adventurers.

In the middle of the eighteenth century Paititi resurfaced, especially in Cuzco, but took on mythic dimensions. Thus, during the rebellion of May 1742, the Peruvian Juan Santos Atahualpa knew that “a cousin brother reigned in the Great Paititi” as reported by Dr. Franklin García Irigoyen. Was it a way to revolt the horribly oppressed people, citing the figure of the Inca?

At the same time, in the other side of the continent, an anonymous Portuguese adventurer drew upon the story of Roberio Dias, little son of one of his compatriots who lived among the Indians, to embark in search of gold and diamonds mines in the depths of the Brazilian rainforest. His endless travel took him the much further he anticipated, until that he has described as an area around a mountain range, south-east / north-west. He discovered a huge city with cyclopean walls, so typical of Inca’s architecture, half covered with vegetation. It seems that he was close to the spanish Peru because he wrote in his manuscript he dreaded to meet an armed troop of that rival nation.

In the nineteenth century Paititi, the third great kingdom of Americas which capital is a city full of hidden treasures for centuries lost deep in the Amazon, is definitely assimilated to the mith of Eldorado, and the one of the golden cities. And by the same movement relegated as a legend by Alexander Humbolt, who was mapped the continent.

This did not prevent Hiran Bingham to found Machu Picchu in 1912, while searching Paititi.

In the 1920s, Sir Percy Harrison Fawcett, a quite eccentric but courageous English officer drew upon the Portuguese manuscript (whose adventure is recounted above) to search for traces of the descendants of the Atlanteans, whose, according to jim, took refuge deep in the Amazon, and were at the origins of pre-Inca cultures. Accumulating evidences from native’s stories and explorations during his eight expeditions, he thought he had discovered the outpost of a great city in the Mato Grosso region, at the foot of a mountain. He disappeared into the jungle on the eve of his advertised discovery.

Fawcett knew a certain mediatization, and gave birth to vocations. Since the 1960s dozens of archaeological expeditions, which sometimes ended tragically, were conducted to find the lost city of Paititi. I will not enumerate them here, but draw two conclusions :

All together, they explored only one hundredth of this continent of dense forest.

And throughout the huge forest area that corresponded to the Antisuyu, remains and even small Inca cities were found. This region, still poorly known, one of the four great provinces of the empire, must have had a capital …

A “legend” that sounds too real

If, as we have seen, it has been assimilated little by little to the Eldorado or the Golden Cities, which are myths or the imaginary distortion of real facts, after 400 years Paititi continues to sharpen, maybe more than ever, the curiosity of archaeologists. Some of the most recognized of them even begin to have the courage to at least consider its possible reality: Indeed many recent discoveries question the dogma imposed by the academy which, in the right line of the Spanish colonialist mentality, refuses since the XVIth century to conceive that in the forest of the “savages” could had been developed any form of civilization.

If the lost kingdom of Paititi in particular arouses so much interest from the professionals, it is because its “legend” has a peculiarity: Its sources are very numerous, and some very reliable, because they are the same ones that allowed us to know the Inca history. Above all, all these sources, however distinct in time and space, converge on the smallest details.

The elements that compose the “legend” of Paititi come from two groups of sources:

These are mostly narratives of chroniclers of the time, who report the testimonies of local Indians or Incas interrogated about Paititi, its location, or what was there. While some authors tended to distort the facts, it was not systematic far from it, and others are deemed much more reliable. The multiplicity and the concordance of the narratives of the time necessarily involves.

Other sources are more recent: they are memories transmitted orally and collected by modern anthropologists from tribes that remained isolated until very recently as the Q’eros, or by the religious from the populations of the valleys north of Cusco, where these stories are told during the vigils for generations, in each family.

Another aspect that appeals is that this “legend” contains not at all fantastic element or chimerical creature. On the contrary, all the descriptions indicate characteristics of the geography of the terrain, of certain buildings, names of places, distances, and even precisely describe a certain way of life, habits, know-how, a particular social organization, etc.

These many realistic details and the multiplicity of sources suggest that everything could not be invented.

PS: Thank you for excusing the spelling mistakes and grammar errors in English

© Vincent Pélissier 2016