Formation of the Inca Empire

The Incas are not the first advanced people who reigned over the Andes: Civilizations of Caral or Chavin before our era, then to quote only them Nazca, Tiwanaku and Huari until the year 1000, have shone by their power as well as by their advanced achievements. By 1200, however, these empires fell after declining, and the Andes again divided into small rival seigneuries.

It is in this context that the Incas would have appeared in the vicinity of Cusco. According to the legend, there are several Ayllus (or families) headed by the 4 Ayar brothers and their respective sisters and wives. They would have settled in the region after a long journey, of which the origin is still very uncertain today.

The land they occupied was a marshy area. Ayar Manco, after the dead of his three brothers, took the title of Manco Cápac, first Inca, and founded the four quarters of what would become the capital of his people: Cuzco, “the navel of the world”. The city was mostly divided between the upper part (Hanan) and the lower part (Hurin), illustrating the politico-religious duality underlying all the Inca society.

The main political scene of the empire is in place. The first Incas succeeding Manco Capac are Sinchi Roca (who is his son), Lloque Yupanqui, Mayta Capac and Capac Yupanqui.

The people ruled by the Inca, whom we call “the Incas” for convenience, is then only one warlike tribe among others. To reinforce themselves, the newcomers unite some around them. During this period, the Incas conquered the region of Lake Titicaca after hardly fought the Collas. They also extend to the valleys of the west coast.

Inca Roca succeeds Capac Yupanqui after the latter dies poisoned. Inca military campaigns weaken the rival Ayarmarcas tribe north of Cusco, before reciprocal marriages brought the two peoples together. According to some chroniclers, Inca Roca would also have made a first foray to the east in the Amazon zone. He married a Chunco (a generic term by which the Incas living on the mountain range designated the inhabitants of the forest)

It was also Inca Roca who founded the “House of Knowledge” in Cusco: the young Inca nobles were taught there morality, religion, administration of the empire, but also mathematics, science, Knowledge of the living and the universe, Andean beliefs, Inca history and Quechua language.

Yahar Huacac succeeds him. During his reign a federated people rebelled and succeeded in sacking Cusco, who owed his salvation only to a providential storm which the assailants took for a bad omen. This first phase of Inca development ended with Viracocha Inca, who extends the Inca territory to the north as to the south of Cusco.

The Golden Age of the Inca Empire

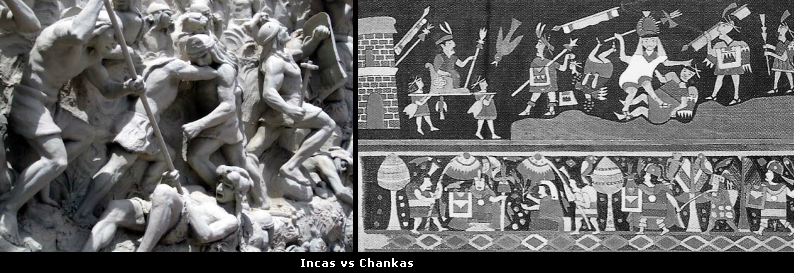

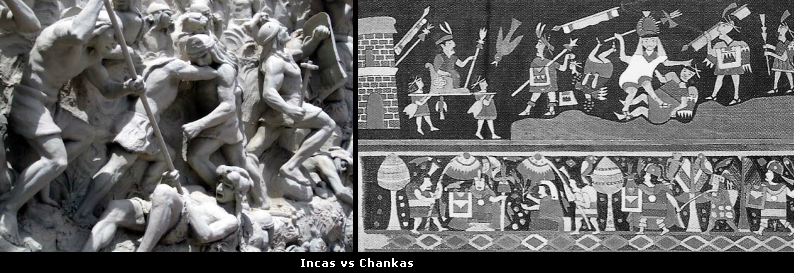

The expansion of the Inca Empire did not exceed that of the great cultures which had preceded it in this part of the Andes. Otherwise, another contemporary civilization is of great size to destroy its ambitions: The Chankas, descendants of the Huari, are an important ethnic group established in the region of Ayachucho, in the northwest.

This rude warrior people finally threatened Cusco at the end of the reign of Viracocha Inca, in 1438, and was about to conquer the city. The old sovereign judges the battle lost beforehand and flies in the mountains with his son and his court. But a prince of another lineage named Cusi Yupanqui decides to resist. Finally, after an epic battle, he prevails over the Chankas.

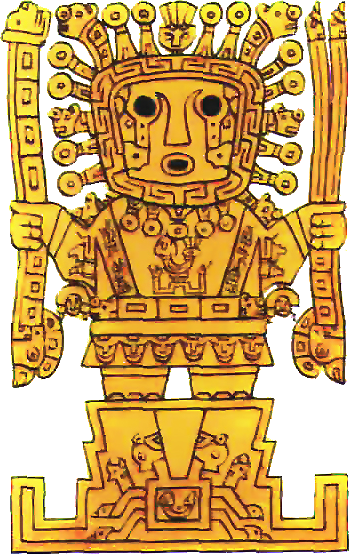

He reformed the cult and then was crowned Inca with the approval of the priest of the sun, took the name of Pachacútec Inca Yupanqui and created a new dynasty. From then on, the Inca sovereigns will consider themselves and will be considered as “Sons of the Sun reigning by divine right over the Elected People”.

Pachacutec initiated a military campaign and occupied most of the Chankas possessions before subduing the Collas revolts and the Lupakas of Lake Titicaca. He then summoned the tribal chiefs and the Inca authorities of the empire’s provinces to the capital, and they decided, or rather it was imposed on them, the sending of workers, food, and building materials. This would become regular. Indeed, the great Inca works began:

In the first years of his reign, Pachacutec emptied Cusco of its inhabitants and elaborated a new pattern of distribution of land, privileging the panacas (lineages of the ancient Incas) and the descendants of the original ayllus, thus attracting to him the good graces of all. Reconstruction began with the channeling of the streams in order to avoid the quagmires during the rainy season and to promote a quality water supply. The king undertakes the reconstruction of the Curicancha, the sacred enclosure until then modest witch became an incredible sanctuary covered with gold, dedicated to the sun and other Inca gods.

Nicknamed the “transformer of the earth” according to Guaman Poma, Pachacutec reformed in depth and improved the inca system of government, drafted laws and created courts, dispatched inspectors using the system of quipus (collars of nodes allowing to record data ) and royal representatives throughout the empire. He founded cities with an exemplary architecture and agricultural model on conquered territories to demonstrate to local peoples the interest of being part of what had become a flourishing empire. He made royal roads, built bridges, and relays for messengers. At the court no one disputed his authority. The mummies of the ancient sovereigns (huacas apus) were kept in the temple and left for the main ceremonies. Pachacutec wished that the principal sacred idols should remain in Cusco, with their servants and goods. Thus he controlled the members of the Panacas (royal lineages) by the fear of reprisals exerted on the family idols.

Pachacutec “travels” in the forest region of Madre De Dios, from where he brought back quantity of gold, medicinal plants and exotic fruits. To the north of Cusco in the mountainous part of the Antisuyu, he founded the citadel of Pisac and occupied the Machu Pichu, where he built a palace to reside on with the Panacas (royal lineages). John E. Rowe, who worked on a recently discovered manuscript, learned that this whole area was the private domain of the Inca, and therefore that this area was sacred, secret, and hardly accessible to the common Incas.

The conquests also underwent unprecedented growth: the rich commercial cities of the south coast agreed to submit to the empire, but it was after a bitter war that the Incas succeeded in annexing the territories of Cajamarca on the Sierra Central and the flourishing Chimu civilization on the north coast.

Many Andean peoples preferred to accept Inca sovereignty and pay tribute rather than to fight. The Incas have a habit of accepting to integrate the god of the people subject to their pantheon, but on condition that their Ayar ancestors were recognized as the creatures named by this god to govern. They thus ensure for themselves, the descendants of these rulers of divine right, a legitimacy in the eyes of these peoples. This system of submission allowed the Inca state to grow rapidly, but was also a factor of fragility because at the first opportunity these tribes remained culturally and militarily quite independent, pressed with taxes, rebelled.

Tupac Inca Yupanqui succeeds Pachacutec: This great general and outstanding strategist professionalised the armies and organized them into squadrons according to the origins of the men, marching with a captain of the same ethnic group at their head and dressed according to their customs. They were divided into units according to the weapons they used to facilitate the command. In battle the soldiers wore tunics of leather or thick cloth with a disc of metal more or less precious on the chest, shields, and helmets adorned with hoopoes. The weapons were essentially chambi (masses), liwi (bolas), spears, axes and fronds. Before launching the assault, his armies produced the greatest possible noise in order to discourage opponents, using drums, trumpets, conches and flutes, howling and singing.

During the reign of Tupac Inca Yupanqui the Incas conquered the territory of the Chachapoyas in the north of Peru and part of the present Ecuador. In the south they occupied the Andean part of present-day Bolivia and Argentina. Some chroniclers report that Tupac Inca Yupanqui sent a gigantic fleet to the Pacific, which, propelled by the favorable Alizes, would have arrived as far as Polynesia …

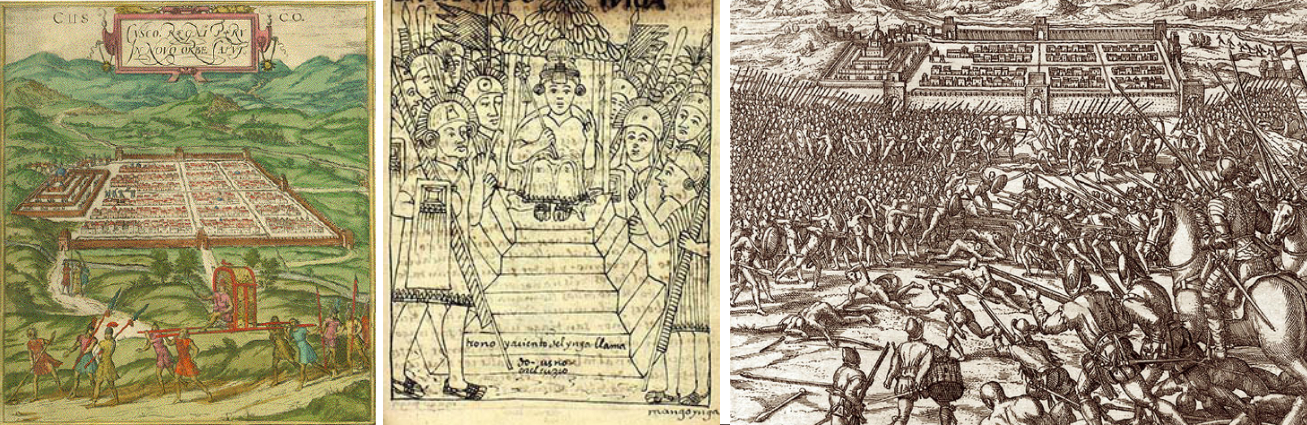

Tupac Inca Yupanqui reduced the attempts of insurrection, dividing the subjugated kingdoms and implanting populations (mitimaes) and garrisons to ensure the security of the empire. During his reign, it was divided into four part and took the name of Tahuantinsuyo, the empire of the four regions: Chinchansuyo (north) Contisuyu (west), Collasuyu (south) and Antisuyu (east). Cusco, the capital, was at the precise point where all four met. Strengthened by his military force, he accentuated the system of tributes into products and obligatory labor (Mita) demanded to submitted peoples.

The decline of the Inca Empire

At the end of the reign of Topa Inca Yupanqui, a series of intrigues at the court of Cusco disrupts his succession. After years of trouble, it is ultimately Huayna Capac who takes control of the empire. The latter conducts a major military campaign in the south, followed by another in the north, where he prefers to settle rather than return to Cusco, which, since the events of his youth, displeased him. He remarried on the spot and had many children. Huyna Cápac spent many years in the north in these states very far from the capital, fighting the many rebellious ethnic groups with his favorite sons, including Atahualpa.

Huayna Cápac finally went to Quito to prepare for his return to the capital, but he fell seriously ill from the smallpox brought by the first Spanish explorers who approached the coast in 1528. On the brink of death he called the priests to designate his heir, Ninan Cuyuchi. But when the dignitaries came to the prince, they found him dead also.

This situation led to a terrible conflict of succession between two of the many children of Huayna Capac: Atahualpa, a prince of the north where he had spent his life, and Huascar, Prince of Cusco. Atahualpa took up arms to claim the power, and conquered at the cost of many bloody battles the northern part of the empire. Only the island of Puno off the coastal city of Tumbès resisted him.

Little by little, Huascar lost ground and the support of his generals in the south, and finally, at the end of another disastrous battle, he was forced to flee and to leave Cusco at the mercy of Atahualpa. It was on this occasion that one of the princes of Cusco, Inca Shock Auqui (Golden Prince), half-brother of Huascar, fearing with reason the terrible punishments awaiting the nobility of the capital, fled towards the northeast by a secret passage, carrying with him the essential of the scholars, nobles and priests. They would have followed the “path of the ancients” and would have gone to “another Cuzco” to protect the knowledge and traditions of the empire.

When the troops of Atahualpa arrived in front of Cusco, the panacas and important lineages of the Hanan Cusco and Huron Cusco who had not fled left the city and prostrated themselves to pay tribute to the new sovereign and recognize him as Inca. The revenge against the Ayllu to which Huáscar belonged was terrible. General Quizquiz had orders to kill all relatives close to Huascar, his wives and sons, including the children to be born… He burned the mummy of his ancestor Túpac Yupanqui, which represented the greatest sacrilege possible.

Then came news of the appearance of white people, bearded and shining in the sun arriving on wooden houses floating by the sea. Atahualpa did not worry about this handful of strangers who landed for the second time on his land, but he was curious because their description corresponded almost perfectly to that of the god Viracocha, who was according to the oldest Andean legends left on the ocean after creating the world, promising the men to return…

The fall of the Inca Empire

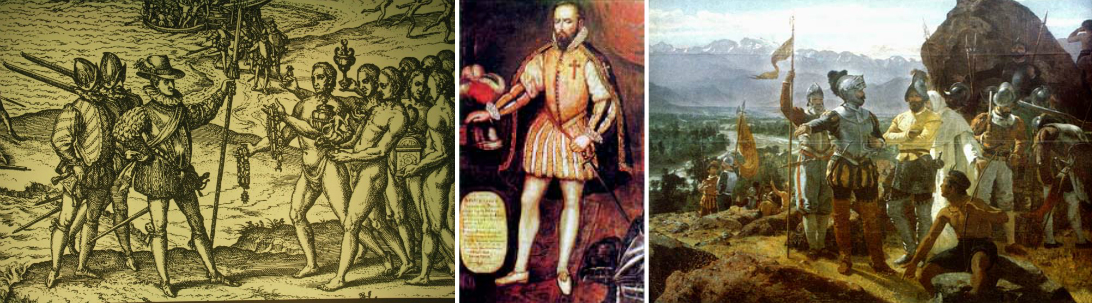

When the Spaniards landed, the civil war was far from over, and many groups still supported Huascar in flight. Francisco Pizarro meets first on one of these groups when he approaches the island of Puno, where he is seen as the savior god who came to restore order after years of murderous conflict. The terrible epidemics propagated by the first European expeditions on the coasts a few years ago have ended up sowing chaos in the empire, which is no more than the shadow of itself.

Pizarro learned from Cortez, the conqueror of the Aztec empire, that the indigenous societies have a pyramidal organization and that, by bringing the sovereign to the head, they are weakened sufficiently to have a chance, by concluding alliances of circumstances, to take control of the entire empire.

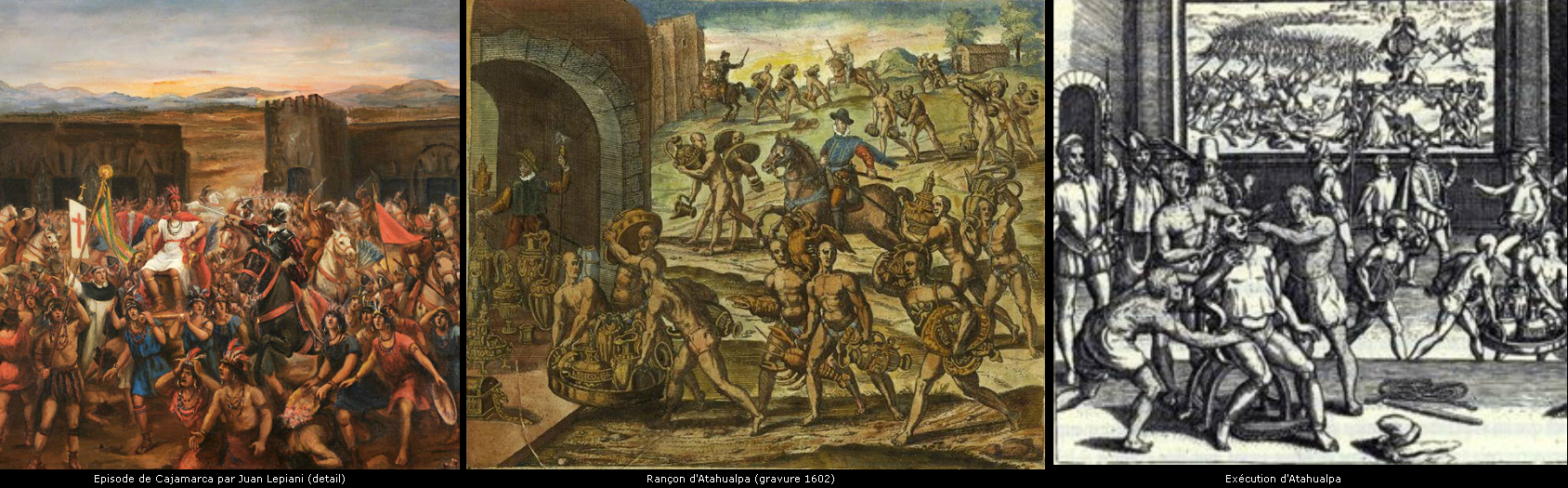

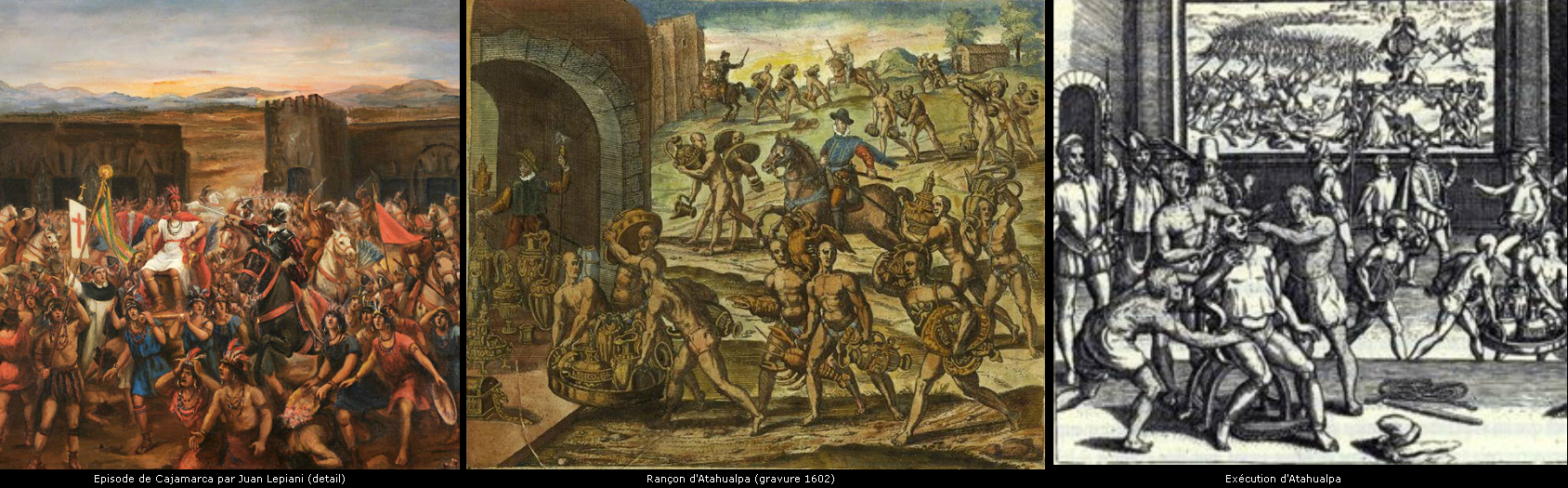

This is exactly what the conquistador will apply, with a certain strategic maestria, but also a reckless deceit and lack of honor, to which the Incas were not at all accustomed. Pizarro with his handful of men manages to capture the powerful Atahualpa during their first diplomatic encounter in Cajamarca, following a truly ambitious surprise operation plan. The Inca generals who came to negotiate the return of their chief under pain of annihilating the Spaniards were cowardly poisoned. The Inca army, deprived of command, fearing for the life of its emperor son of the sun, dispersed.

Atahualpa then promised a huge ransom in gold and silver to the conquistadors in exchange for his freedom. It flowed very quickly, essentially from the north of the empire of which Atahualpa originated. The Spaniards found Huascar and also imprisoned him, but Atahualpa seized his chance and executed his rival. The ransom finally united (a large room filled of gold to the ceiling), Pizarro could in no case leave Atahualpa alive: he betrayed his promess and ordered his execution under a false pretext. The Spaniards then plundered many sacred places, and proceeded to Cusco.

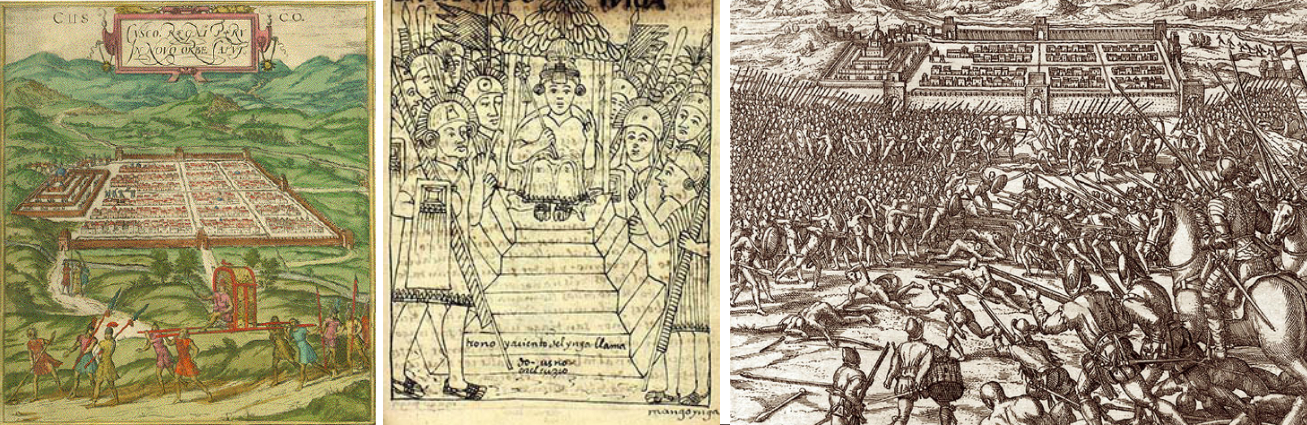

They were supported by the numerous tribes formerly subject to the Incas, who saw in it the means of escaping from their former masters, and from the heavy tax which they were obliged to pay them. During his march on Cusco, Pizarro received another major support: that of Huascar’s successor, a certain Manco Inca, who offered to help him conquer the city, still in the hands of a general of Atahualpa. In exchange, Manco was to be recognized as sovereign by the Spaniards and their allies.

Pizarro accepted of course, but once the capital conquered at the end of 1533, Manco Inca displeased: He was humiliated, and gradually reduced to the role of puppet, then prisoner in his own palace. The Spanish thirst for gold was increasingly pressing, and he struggled to preserve the sacred treasures of his people. Managing to escape from the city, he then united an immense army and besieged the city, occupying many quarters. He also reconquered the whole center of the empire, and besieged Lima, where Pizarro had intrenched himself.

However, his troops lacked food and were combativeness after years of epidemics and civil war : the allied tribes of the Spaniards were too resistant and he failed to overcome them. Manco Inca then united throughout the empire all the sacred objects of gold (this metal had the color of the sun for the Incas). No longer able to hold the siege of Cusco, he took refuge with that fabulous treasure in the mountains to the north of the capital. The chroniclers of the time speak of a caravan of 20,000 llamas loaded with gold that would have been seen crossing the mountains near a certain Vilcabamba.

When the reinforcements sent by Pizarro from Lima arrived in Cusco, they found the city in ruins in the hands of one of his lieutenants, Diego de Almagro, who intends to keep it under his control. A battle between Spaniards follows, and Almagro prevails, thus initiating a war between Spaniards for the control of the conquered lands.

Nobody knows what Manco Inca did for a year: Did he follow in the footsteps of the Golden Prince who had entrenched himself in “another Cusco” with all the Inca sages, in order to shelter the mummies of his ancestors and sacred objects? No one knows. The supporters of Manco taken prisoner by Almagro will finally, after torture, tell him that “The Inca, the crowns and many other things are at the junction of the river Paititi and the river Pamara, three days of march from the Manu River “, which didn’t advance the Spaniards, who were unaware of the Amazon zone and who must remain in the city.

When a detachment of the conquistador’s cavalry finds Manco Inca in June 1537, he is in Ollantaytambo with a small troop and folded on Chuquichaca, then Vitcos. But with him, he no longer has any cumbersome treasure… Pizarro will finally take Cusco back to Almagro in 1538. He then launches in the track of Manco Inca, which leads from the mountains little accessible a real guerilla against the Spaniards, attacking the supplying convoys, humiliating troops sent to capture him, inciting the population to revolt against the occupier… Manco Inca is considered to direct the resistance from Vilcabamba, a city of mountains whose real location has been lost, but which the Spaniards knew well because they sent emissaries there.

In 1541, Pizarro was assassinated by supporters of his former lieutenant Almagro. The murderers took refuge at Manco Inca in Vilcabamba. The latter agrees to receive them, and offers them protection. However, as soon as the new Viceroy of Peru offered them absolution, they betrayed the Inca ruler and assassinated him in 1545. They were caught up in their flight and beheaded.

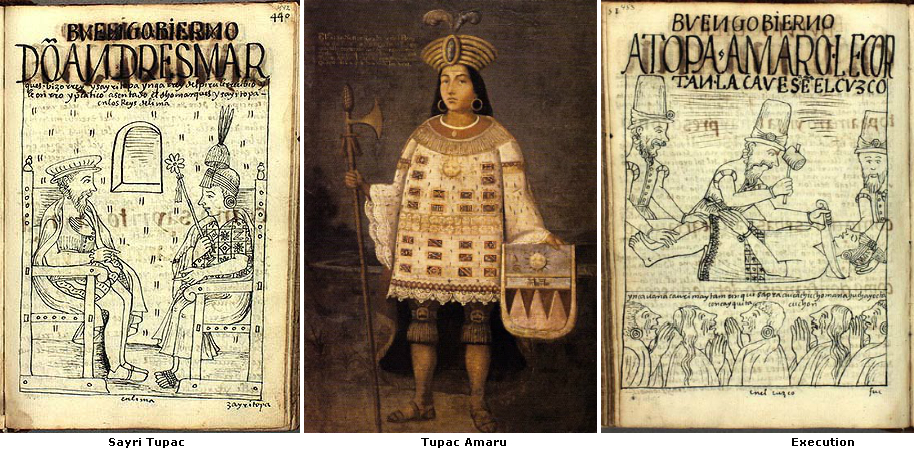

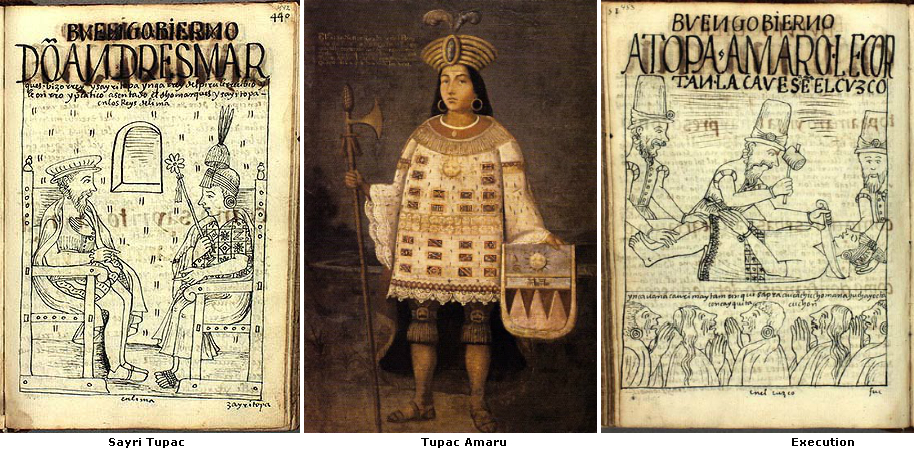

Sayri Túpac, Manco’s eldest son, took over and initiated a more diplomatic phase of the resistance, succeeding in concluding a peace treaty with the new Viceroy, which left the incas the territory of the mountains they occupied. This situation did not last and as early as 1560 the resistance takes up arms with Titu Cusi Yupanqui, which launched an appeal throughout the old empire without knowing the success hoped for. Forced to resume negotiations, Titu Cusi succeeded in enforcing the treaty signed with his predecessor. He was finally assassinated by a monk whom he had allowed to penetrate his lands…

Tupac Amaru succeeded him in 1571 and restarted the fight against Spaniards. Francisco de Toledo, the new viceroy of irascible character, has the task of completely subduing what had become a Spanish colony, and of eradicating the persistent idolatry. Unable to tolerate the geographical division of power established during the treaty with Titu Cusi, he used the death of an emissary as a pretext to conquer “by fire and blood” the last Inca territory. At the end of May 1572, the invasion began.

Instead of fire and blood, almost nothing happened: After taking the bridge of Choquechaka, the Spaniards advance by the valley of the Urubamba by crushing a weak resistance. They cross a pass and go on the Cordillera of Pantiacolla, where they took possession of the small fortified places of the zone. Finally on 24 June 1572 they entered Vilcabamba, but to find it emptied and burnt. Tupac Amaru is present with a small guard, he surrenders.

Enchanted and humiliated, the “Last Inca” is brought back triumphantly to Cuzco. Him, the great defender of the Incan faith, will go so far as to ask to be baptized to demonstrate the end of any rebellion. This will not prevent Francisco de Toledo from having him executed in the public square by decapitation, before 10,000 Indians shouting their sadness and their pain.

The Genocide

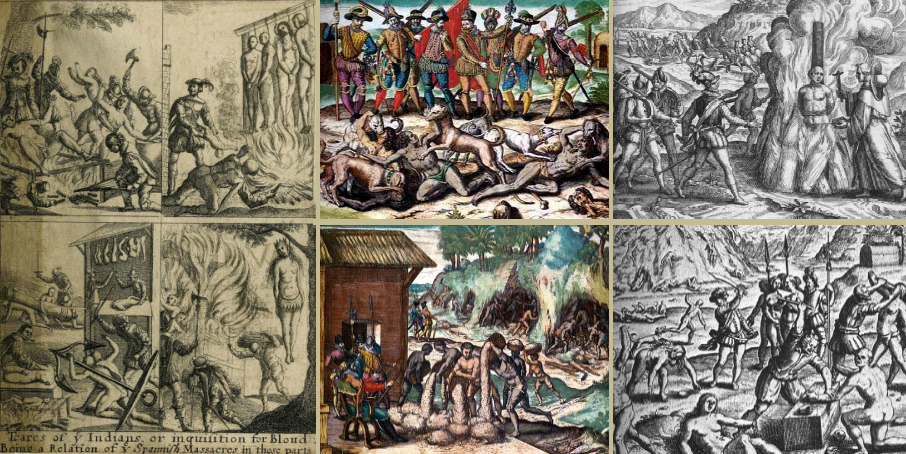

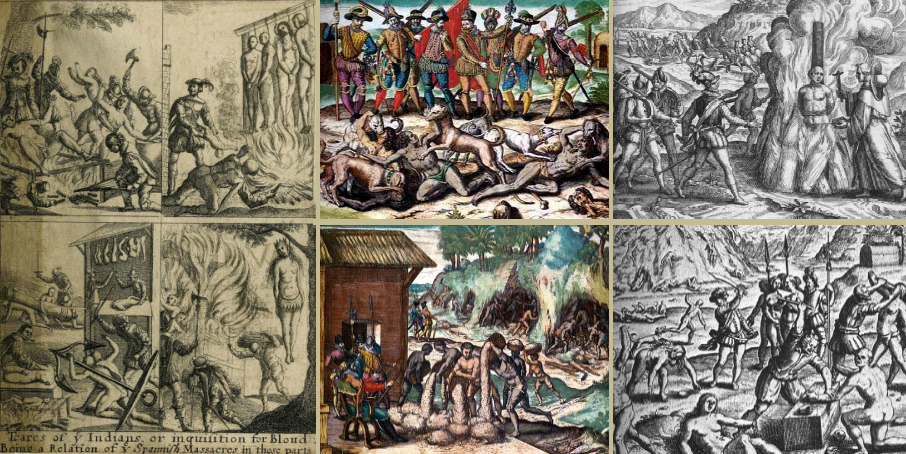

Viceroy Toledo instituted a reform of the indigenous habitat which made it possible to regroup the useful “mass of work”, subjected to compulsory labor, without remuneration, so to speak clearly reduced in slavery. The entire Inca agricultural system, very productive, is annihilated to favor productions destined for export. The organization of farms in gigantic plantations drastically reduces yield, leading to terrible famines in the population.

Indigenous slaves are especially affected in the terrible mines, where it is estimated that out of 12 million inhabitants, 5 million men, women and children perish in 25 years, victims of the insatiable thirst for gold and the inhumanity shown by the Spaniards towards them. In some provinces rich in gold or silver, two-thirds of the population is enslaved in the mines and perishes there. So much so that the Spaniards will finally have to bring “cargoes” of black slaves to replace them …

The diseases of the old continent are also continuing to increase their harvest of victims on this weakened population, notably smallpox, which causes a horrific death and against which the Indians had no immunity, mowing millions of lives.

If some religious rebels against this unnamed barbarism which remains, today, one of the worst human genocides of all ages, most religious authorities are submit to the colossal political power that the Spanish crown take from these exportations of precious metal to Europe. Their argument for closing their eyes: “The right to govern and subdue the Indians is very just and clear, since the power of the Church extended to the Christian princes.”

For the laudable purpose of saving the souls of the Indians, the Inquisition made terrible ravages throughout the 16th and 17th century in the Andes, committing far worse exactions in these remote lands than in Europe. All could serve, and served, as a pretext for religious fanatics in these heretical lands by nature, necessarily still far from mastering the many rigid subtleties of the Catholic faith of the time, to burn, torture, mutilate, etc …

The Inquisition participates actively and methodically in the annihilation by fire of all traces of local culture, considered heretical. As if the simple extermination of the population was not enough, Viceroy Toledo encouraged this “erasure” of all traces of indigenous culture because he saw in it the persistence of an Inca identity, a pride that he identifies as a threat and wants to break down permanently. He even censures the Spanish chroniclers who describe the Incan history and customs by remaining a little too impartial: to make thinking in Europe that the native people are monsters, savages with barbaric customs made it easier to justify slavery, and to reap the rewards profits…

The Inca Empire was estimated between 8 and 12 million subjects in 1530.

In 1600, they were only 2 million.

In 1754, there were only 615,000 Indians left.

PS: Thank you for excusing the spelling mistakes and grammar errors in English

© Vincent Pélissier 2016

Formation of the Inca Empire

The Incas are not the first advanced people who reigned over the Andes: Civilizations of Caral or Chavin before our era, then to quote only them Nazca, Tiwanaku and Huari until the year 1000, have shone by their power as well as by their advanced achievements. By 1200, however, these empires fell after declining, and the Andes again divided into small rival seigneuries.

It is in this context that the Incas would have appeared in the vicinity of Cusco. According to the legend, there are several Ayllus (or families) headed by the 4 Ayar brothers and their respective sisters and wives. They would have settled in the region after a long journey, of which the origin is still very uncertain today.

The land they occupied was a marshy area. Ayar Manco, after the dead of his three brothers, took the title of Manco Cápac, first Inca, and founded the four quarters of what would become the capital of his people: Cuzco, “the navel of the world”. The city was mostly divided between the upper part (Hanan) and the lower part (Hurin), illustrating the politico-religious duality underlying all the Inca society.

The main political scene of the empire is in place. The first Incas succeeding Manco Capac are Sinchi Roca (who is his son), Lloque Yupanqui, Mayta Capac and Capac Yupanqui.

The people ruled by the Inca, whom we call “the Incas” for convenience, is then only one warlike tribe among others. To reinforce themselves, the newcomers unite some around them. During this period, the Incas conquered the region of Lake Titicaca after hardly fought the Collas. They also extend to the valleys of the west coast.

Inca Roca succeeds Capac Yupanqui after the latter dies poisoned. Inca military campaigns weaken the rival Ayarmarcas tribe north of Cusco, before reciprocal marriages brought the two peoples together. According to some chroniclers, Inca Roca would also have made a first foray to the east in the Amazon zone. He married a Chunco (a generic term by which the Incas living on the mountain range designated the inhabitants of the forest)

It was also Inca Roca who founded the “House of Knowledge” in Cusco: the young Inca nobles were taught there morality, religion, administration of the empire, but also mathematics, science, Knowledge of the living and the universe, Andean beliefs, Inca history and Quechua language.

Yahar Huacac succeeds him. During his reign a federated people rebelled and succeeded in sacking Cusco, who owed his salvation only to a providential storm which the assailants took for a bad omen. This first phase of Inca development ended with Viracocha Inca, who extends the Inca territory to the north as to the south of Cusco.

The Golden Age of the Inca Empire

The expansion of the Inca Empire did not exceed that of the great cultures which had preceded it in this part of the Andes. Otherwise, another contemporary civilization is of great size to destroy its ambitions: The Chankas, descendants of the Huari, are an important ethnic group established in the region of Ayachucho, in the northwest.

This rude warrior people finally threatened Cusco at the end of the reign of Viracocha Inca, in 1438, and was about to conquer the city. The old sovereign judges the battle lost beforehand and flies in the mountains with his son and his court. But a prince of another lineage named Cusi Yupanqui decides to resist. Finally, after an epic battle, he prevails over the Chankas.

He reformed the cult and then was crowned Inca with the approval of the priest of the sun, took the name of Pachacútec Inca Yupanqui and created a new dynasty. From then on, the Inca sovereigns will consider themselves and will be considered as “Sons of the Sun reigning by divine right over the Elected People”.

Pachacutec initiated a military campaign and occupied most of the Chankas possessions before subduing the Collas revolts and the Lupakas of Lake Titicaca. He then summoned the tribal chiefs and the Inca authorities of the empire’s provinces to the capital, and they decided, or rather it was imposed on them, the sending of workers, food, and building materials. This would become regular. Indeed, the great Inca works began:

In the first years of his reign, Pachacutec emptied Cusco of its inhabitants and elaborated a new pattern of distribution of land, privileging the panacas (lineages of the ancient Incas) and the descendants of the original ayllus, thus attracting to him the good graces of all. Reconstruction began with the channeling of the streams in order to avoid the quagmires during the rainy season and to promote a quality water supply. The king undertakes the reconstruction of the Curicancha, the sacred enclosure until then modest witch became an incredible sanctuary covered with gold, dedicated to the sun and other Inca gods.

Nicknamed the “transformer of the earth” according to Guaman Poma, Pachacutec reformed in depth and improved the inca system of government, drafted laws and created courts, dispatched inspectors using the system of quipus (collars of nodes allowing to record data ) and royal representatives throughout the empire. He founded cities with an exemplary architecture and agricultural model on conquered territories to demonstrate to local peoples the interest of being part of what had become a flourishing empire. He made royal roads, built bridges, and relays for messengers. At the court no one disputed his authority. The mummies of the ancient sovereigns (huacas apus) were kept in the temple and left for the main ceremonies. Pachacutec wished that the principal sacred idols should remain in Cusco, with their servants and goods. Thus he controlled the members of the Panacas (royal lineages) by the fear of reprisals exerted on the family idols.

Pachacutec “travels” in the forest region of Madre De Dios, from where he brought back quantity of gold, medicinal plants and exotic fruits. To the north of Cusco in the mountainous part of the Antisuyu, he founded the citadel of Pisac and occupied the Machu Pichu, where he built a palace to reside on with the Panacas (royal lineages). John E. Rowe, who worked on a recently discovered manuscript, learned that this whole area was the private domain of the Inca, and therefore that this area was sacred, secret, and hardly accessible to the common Incas.

The conquests also underwent unprecedented growth: the rich commercial cities of the south coast agreed to submit to the empire, but it was after a bitter war that the Incas succeeded in annexing the territories of Cajamarca on the Sierra Central and the flourishing Chimu civilization on the north coast.

Many Andean peoples preferred to accept Inca sovereignty and pay tribute rather than to fight. The Incas have a habit of accepting to integrate the god of the people subject to their pantheon, but on condition that their Ayar ancestors were recognized as the creatures named by this god to govern. They thus ensure for themselves, the descendants of these rulers of divine right, a legitimacy in the eyes of these peoples. This system of submission allowed the Inca state to grow rapidly, but was also a factor of fragility because at the first opportunity these tribes remained culturally and militarily quite independent, pressed with taxes, rebelled.

Tupac Inca Yupanqui succeeds Pachacutec: This great general and outstanding strategist professionalised the armies and organized them into squadrons according to the origins of the men, marching with a captain of the same ethnic group at their head and dressed according to their customs. They were divided into units according to the weapons they used to facilitate the command. In battle the soldiers wore tunics of leather or thick cloth with a disc of metal more or less precious on the chest, shields, and helmets adorned with hoopoes. The weapons were essentially chambi (masses), liwi (bolas), spears, axes and fronds. Before launching the assault, his armies produced the greatest possible noise in order to discourage opponents, using drums, trumpets, conches and flutes, howling and singing.

During the reign of Tupac Inca Yupanqui the Incas conquered the territory of the Chachapoyas in the north of Peru and part of the present Ecuador. In the south they occupied the Andean part of present-day Bolivia and Argentina. Some chroniclers report that Tupac Inca Yupanqui sent a gigantic fleet to the Pacific, which, propelled by the favorable Alizes, would have arrived as far as Polynesia …

Tupac Inca Yupanqui reduced the attempts of insurrection, dividing the subjugated kingdoms and implanting populations (mitimaes) and garrisons to ensure the security of the empire. During his reign, it was divided into four part and took the name of Tahuantinsuyo, the empire of the four regions: Chinchansuyo (north) Contisuyu (west), Collasuyu (south) and Antisuyu (east). Cusco, the capital, was at the precise point where all four met. Strengthened by his military force, he accentuated the system of tributes into products and obligatory labor (Mita) demanded to submitted peoples.

The Decline of the Inca Empire

At the end of the reign of Topa Inca Yupanqui, a series of intrigues at the court of Cusco disrupts his succession. After years of trouble, it is ultimately Huayna Capac who takes control of the empire. The latter conducts a major military campaign in the south, followed by another in the north, where he prefers to settle rather than return to Cusco, which, since the events of his youth, displeased him. He remarried on the spot and had many children. Huyna Cápac spent many years in the north in these states very far from the capital, fighting the many rebellious ethnic groups with his favorite sons, including Atahualpa.

Huayna Cápac finally went to Quito to prepare for his return to the capital, but he fell seriously ill from the smallpox brought by the first Spanish explorers who approached the coast in 1528. On the brink of death he called the priests to designate his heir, Ninan Cuyuchi. But when the dignitaries came to the prince, they found him dead also.

This situation led to a terrible conflict of succession between two of the many children of Huayna Capac: Atahualpa, a prince of the north where he had spent his life, and Huascar, Prince of Cusco. Atahualpa took up arms to claim the power, and conquered at the cost of many bloody battles the northern part of the empire. Only the island of Puno off the coastal city of Tumbès resisted him.

Little by little, Huascar lost ground and the support of his generals in the south, and finally, at the end of another disastrous battle, he was forced to flee and to leave Cusco at the mercy of Atahualpa. It was on this occasion that one of the princes of Cusco, Inca Shock Auqui (Golden Prince), half-brother of Huascar, fearing with reason the terrible punishments awaiting the nobility of the capital, fled towards the northeast by a secret passage, carrying with him the essential of the scholars, nobles and priests. They would have followed the “path of the ancients” and would have gone to “another Cuzco” to protect the knowledge and traditions of the empire.

When the troops of Atahualpa arrived in front of Cusco, the panacas and important lineages of the Hanan Cusco and Huron Cusco who had not fled left the city and prostrated themselves to pay tribute to the new sovereign and recognize him as Inca. The revenge against the Ayllu to which Huáscar belonged was terrible. General Quizquiz had orders to kill all relatives close to Huascar, his wives and sons, including the children to be born… He burned the mummy of his ancestor Túpac Yupanqui, which represented the greatest sacrilege possible.

Then came news of the appearance of white people, bearded and shining in the sun arriving on wooden houses floating by the sea. Atahualpa did not worry about this handful of strangers who landed for the second time on his land, but he was curious because their description corresponded almost perfectly to that of the god Viracocha, who was according to the oldest Andean legends left on the ocean after creating the world, promising the men to return…

The fall of the Inca Empire

When the Spaniards landed, the civil war was far from over, and many groups still supported Huascar in flight. Francisco Pizarro meets first on one of these groups when he approaches the island of Puno, where he is seen as the savior god who came to restore order after years of murderous conflict. The terrible epidemics propagated by the first European expeditions on the coasts a few years ago have ended up sowing chaos in the empire, which is no more than the shadow of itself.

Pizarro learned from Cortez, the conqueror of the Aztec empire, that the indigenous societies have a pyramidal organization and that, by bringing the sovereign to the head, they are weakened sufficiently to have a chance, by concluding alliances of circumstances, to take control of the entire empire.

This is exactly what the conquistador will apply, with a certain strategic maestria, but also a reckless deceit and lack of honor, to which the Incas were not at all accustomed. Pizarro with his handful of men manages to capture the powerful Atahualpa during their first diplomatic encounter in Cajamarca, following a truly ambitious surprise operation plan. The Inca generals who came to negotiate the return of their chief under pain of annihilating the Spaniards were cowardly poisoned. The Inca army, deprived of command, fearing for the life of its emperor son of the sun, dispersed.

Atahualpa then promised a huge ransom in gold and silver to the conquistadors in exchange for his freedom. It flowed very quickly, essentially from the north of the empire of which Atahualpa originated. The Spaniards found Huascar and also imprisoned him, but Atahualpa seized his chance and executed his rival. The ransom finally united (a large room filled of gold to the ceiling), Pizarro could in no case leave Atahualpa alive: he betrayed his promess and ordered his execution under a false pretext. The Spaniards then plundered many sacred places, and proceeded to Cusco.

They were supported by the numerous tribes formerly subject to the Incas, who saw in it the means of escaping from their former masters, and from the heavy tax which they were obliged to pay them. During his march on Cusco, Pizarro received another major support: that of Huascar’s successor, a certain Manco Inca, who offered to help him conquer the city, still in the hands of a general of Atahualpa. In exchange, Manco was to be recognized as sovereign by the Spaniards and their allies.

Pizarro accepted of course, but once the capital conquered at the end of 1533, Manco Inca displeased: He was humiliated, and gradually reduced to the role of puppet, then prisoner in his own palace. The Spanish thirst for gold was increasingly pressing, and he struggled to preserve the sacred treasures of his people. Managing to escape from the city, he then united an immense army and besieged the city, occupying many quarters. He also reconquered the whole center of the empire, and besieged Lima, where Pizarro had intrenched himself.

However, his troops lacked food and were combativeness after years of epidemics and civil war : the allied tribes of the Spaniards were too resistant and he failed to overcome them. Manco Inca then united throughout the empire all the sacred objects of gold (this metal had the color of the sun for the Incas). No longer able to hold the siege of Cusco, he took refuge with that fabulous treasure in the mountains to the north of the capital. The chroniclers of the time speak of a caravan of 20,000 llamas loaded with gold that would have been seen crossing the mountains near a certain Vilcabamba.

When the reinforcements sent by Pizarro from Lima arrived in Cusco, they found the city in ruins in the hands of one of his lieutenants, Diego de Almagro, who intends to keep it under his control. A battle between Spaniards follows, and Almagro prevails, thus initiating a war between Spaniards for the control of the conquered lands.

Nobody knows what Manco Inca did for a year: Did he follow in the footsteps of the Golden Prince who had entrenched himself in “another Cusco” with all the Inca sages, in order to shelter the mummies of his ancestors and sacred objects? No one knows. The supporters of Manco taken prisoner by Almagro will finally, after torture, tell him that “The Inca, the crowns and many other things are at the junction of the river Paititi and the river Pamara, three days of march from the Manu River “, which didn’t advance the Spaniards, who were unaware of the Amazon zone and who must remain in the city.

When a detachment of the conquistador’s cavalry finds Manco Inca in June 1537, he is in Ollantaytambo with a small troop and folded on Chuquichaca, then Vitcos. But with him, he no longer has any cumbersome treasure… Pizarro will finally take Cusco back to Almagro in 1538. He then launches in the track of Manco Inca, which leads from the mountains little accessible a real guerilla against the Spaniards, attacking the supplying convoys, humiliating troops sent to capture him, inciting the population to revolt against the occupier… Manco Inca is considered to direct the resistance from Vilcabamba, a city of mountains whose real location has been lost, but which the Spaniards knew well because they sent emissaries there.

In 1541, Pizarro was assassinated by supporters of his former lieutenant Almagro. The murderers took refuge at Manco Inca in Vilcabamba. The latter agrees to receive them, and offers them protection. However, as soon as the new Viceroy of Peru offered them absolution, they betrayed the Inca ruler and assassinated him in 1545. They were caught up in their flight and beheaded.

Sayri Túpac, Manco’s eldest son, took over and initiated a more diplomatic phase of the resistance, succeeding in concluding a peace treaty with the new Viceroy, which left the incas the territory of the mountains they occupied. This situation did not last and as early as 1560 the resistance takes up arms with Titu Cusi Yupanqui, which launched an appeal throughout the old empire without knowing the success hoped for. Forced to resume negotiations, Titu Cusi succeeded in enforcing the treaty signed with his predecessor. He was finally assassinated by a monk whom he had allowed to penetrate his lands…

Tupac Amaru succeeded him in 1571 and restarted the fight against Spaniards. Francisco de Toledo, the new viceroy of irascible character, has the task of completely subduing what had become a Spanish colony, and of eradicating the persistent idolatry. Unable to tolerate the geographical division of power established during the treaty with Titu Cusi, he used the death of an emissary as a pretext to conquer “by fire and blood” the last Inca territory. At the end of May 1572, the invasion began.

Instead of fire and blood, almost nothing happened: After taking the bridge of Choquechaka, the Spaniards advance by the valley of the Urubamba by crushing a weak resistance. They cross a pass and go on the Cordillera of Pantiacolla, where they took possession of the small fortified places of the zone. Finally on 24 June 1572 they entered Vilcabamba, but to find it emptied and burnt. Tupac Amaru is present with a small guard, he surrenders.

Enchanted and humiliated, the “Last Inca” is brought back triumphantly to Cuzco. Him, the great defender of the Incan faith, will go so far as to ask to be baptized to demonstrate the end of any rebellion. This will not prevent Francisco de Toledo from having him executed in the public square by decapitation, before 10,000 Indians shouting their sadness and their pain.

The Genocide

Viceroy Toledo instituted a reform of the indigenous habitat which made it possible to regroup the useful “mass of work”, subjected to compulsory labor, without remuneration, so to speak clearly reduced in slavery. The entire Inca agricultural system, very productive, is annihilated to favor productions destined for export. The organization of farms in gigantic plantations drastically reduces yield, leading to terrible famines in the population.

Indigenous slaves are especially affected in the terrible mines, where it is estimated that out of 12 million inhabitants, 5 million men, women and children perish in 25 years, victims of the insatiable thirst for gold and the inhumanity shown by the Spaniards towards them. In some provinces rich in gold or silver, two-thirds of the population is enslaved in the mines and perishes there. So much so that the Spaniards will finally have to bring “cargoes” of black slaves to replace them …

The diseases of the old continent are also continuing to increase their harvest of victims on this weakened population, notably smallpox, which causes a horrific death and against which the Indians had no immunity, mowing millions of lives.

If some religious rebels against this unnamed barbarism which remains, today, one of the worst human genocides of all ages, most religious authorities are submit to the colossal political power that the Spanish crown take from these exportations of precious metal to Europe. Their argument for closing their eyes: “The right to govern and subdue the Indians is very just and clear, since the power of the Church extended to the Christian princes.”

For the laudable purpose of saving the souls of the Indians, the Inquisition made terrible ravages throughout the 16th and 17th century in the Andes, committing far worse exactions in these remote lands than in Europe. All could serve, and served, as a pretext for religious fanatics in these heretical lands by nature, necessarily still far from mastering the many rigid subtleties of the Catholic faith of the time, to burn, torture, mutilate, etc …

The Inquisition participates actively and methodically in the annihilation by fire of all traces of local culture, considered heretical. As if the simple extermination of the population was not enough, Viceroy Toledo encouraged this “erasure” of all traces of indigenous culture because he saw in it the persistence of an Inca identity, a pride that he identifies as a threat and wants to break down permanently. He even censures the Spanish chroniclers who describe the Incan history and customs by remaining a little too impartial: to make thinking in Europe that the native people are monsters, savages with barbaric customs made it easier to justify slavery, and to reap the rewards profits…

The Inca Empire was estimated between 8 and 12 million subjects in 1530.

In 1600, they were only 2 million.

In 1754, there were only 615,000 Indians left.

PS: Thank you for excusing the spelling mistakes and grammar errors in English

© Vincent Pélissier 2016